The People of the Book

A long long time ago (by internet standards), in a faraway land (I dunno, probably California), a bearded man from a Jewish family sat down to write a book. And in that book he set out to teach people how to think well, so that humanity may at last achieve wisdom and salvation. This is apparently something that bearded men from Jewish families are prone to try every few centuries or so. And the art of thinking well he wrote about was known as Rationality.

And around that book, which was then known as “The Rationality Sequences”, gathered wise women and men who accepted everything unquestioningly nitpicked every single sentence and equation and even the entire goal of the book. And yet basically everyone who read The Sequences agreed that they are an excellent guide to reasoning well, that everything in them is so simple and true that it all seems completely obvious in hindsight. Of course, this is exactly what the book warned them will happen. And this group of people who read The Sequences came to be known as the Rationalist Community. Although, being proper rationalists, the group kept arguing for years over whether that was a good name or not.

And lo, other people saw them reading The Sequences and having a good time. And the others spake thus to the rationalists: “LOL, you’re a bunch of nerds in a dumbass cult.” And the rationalists patiently explained that no, the entire art was about thinking independently. And that as he was writing The Sequences, Eliezer anticipated that they will be so fun to read that people will forget to be skeptical, and dedicated an entire huge section of the book to avoiding groupthink and cultiness. And that even though every two rationalists agree on 95% of the book’s conclusions, they spend all their time arguing over the 5% they disagree on, lest anyone accuse them of not being skeptical enough.

On the other hand, the rationalists confirmed that yes, they were a bunch of nerds.

And the others didn’t relent and spake thus to the rationalists: “So what are you nerds doing with your fancy rationality other than squabbling about it on an internet forum?” And the rationalists didn’t answer because they and their friends were too busy helping the needy, and spreading the art, and launching a bunch of start-ups, and advancing science, and saving humanity from extinction.

And yet the others persisted and spake thus to the rationalists: “OMG you guys, that book is like so 2007. Get with the program, the hip place to be now is post-rationality.” And the rationalists asked what errors there were in the book that it should be discarded in favor of something new? But the answer is that there isn’t anything wrong with The Sequences, and they successfully anticipated 9 years ago basically every challenge thrown at them since, and all of you should go and read them right now. But these very smug “postrationalists” did contribute to an annoying aura of unfashionability that formed around LessWrong and keeps new people from benefitting from it.

This is a good place to stop reading this post and start reading The Sequences – they’re pretty long (vita brevis ars longa and all that) and are also better written. In case you haven’t noticed yet, all the links in orange are to LessWrong and the rationality sequences, to give you a taste of the massive breadth of ideas they cover. If you don’t like clicking on links for some reason, I’ll give a short overview of how I see rationality and vent a bit about “postrationalists”.

From Huitzilopochtli to Rationality

Humanity went from thinking that the sun was a hummingbird-shaped warrior god requiring human sacrifice to using solar radiation pressure to power interplanetary spacecraft. We credit most impressive achievements like that to science, and some to Al Gore. Science started working when it noticed a couple of things:

- The hummingbird god sounds super cool, but coolness is a bad indicator of whether something is true. Instead, we can find out what is true by looking at it. Early scientists believed that “looking at it” meant “looking at the sun directly”, that didn’t work out well. Later scientists expanded that idea a bit to mean learning about reality from observing evidence.

- The best way to organize and express scientifically what we know about reality seems to be by putting numbers on it. Reality is very complex and our information is very limited, so we need to use numbers that represent incomplete knowledge. The use of numbers to talk about incomplete knowledge is described by probability theory.

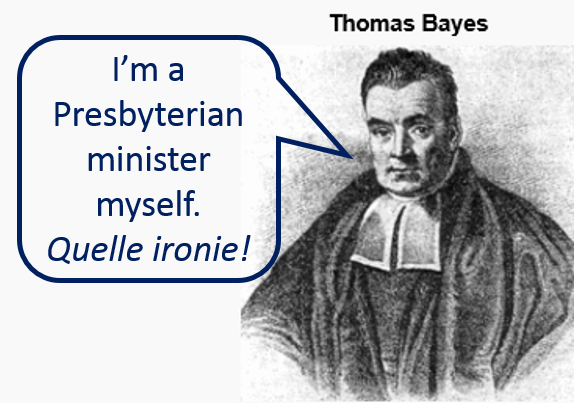

It also turns out that if you ask probability theory how you should learn about reality from observing evidence, it will tell you that while the actual implementation may differ wildly from case to case, at the core of it you should be doing something that looks like Bayes’ theorem. Since in popular culture the label “rational” is usually applied to utterly irrational strawman characters, the term “Bayesian” is sometimes used in the rationality community instead.

Hey, look! Someone wrote a great book called Probability Theory: The Logic of Science.

“Figuring out what reality is like” is something that scientists get paid for, but non-scientists occasionally find uncovering the truth useful as well. Perhaps you want to know how long a project will take you to finish, how likely a roulette wheel is to come up red, whether you have breast cancer or not. That seems simple enough, but all the links you didn’t click on in the previous sentence demonstrate that humans systematically suck at answering these simple questions, and many many many more.

Why is it hard for our brains to simply reject things that are false and believe things that are true? It unfortunately turns out that instead of pristine engines of perfect reasoning inside our heads we are stuck will kludgy, squishy, meat-computer monkey brains. And monkey brains will believe an idea for many reasons:

- The idea seems nice and pleasant to believe in.

- It is politically expedient to believe in the idea.

- The idea props up our self esteem.

- People around us say the idea out loud and repeat it.

- The idea is something we try to convince others of, and we lie better when we believe in the lie ourselves.

- The idea fits in with other wrong ideas we lug around in our brains.

- An authoritative-looking person told us it’s true and we never bothered to check.

- On very rare occasion, we believe an idea because we have seen evidence that shows it to be true.

You may have heard of another great book, this one’s about the ways our brains are predictably wrong about stuff all the time, it’s called Thinking Fast and Slow.

The bad news is that trying to teach your kludgy monkey brain to overcome the fact that it’s a kludgy monkey brain is confusing, difficult and unpleasant. Intelligence, expertise and general awareness of biases don’t help much in this pursuit, and may even actively derail you. Not only is becoming fully rational quite impossible, even starting to make progress is a challenge: it requires overcoming the huge bias blindspot that prevents you from even accepting that you may be irrational on occasion. Your brain will continue to insist to you that it’s perfectly reasonable, even as it’s holding wrong, harmful and even contradictory beliefs.

The good news is that you aren’t alone: there are rationalists in the Bronx and in Bermuda, transgender mathematician rationalists and religious lawyer rationalists, polyamorous communists and conservative asexual rationalists. There are meetups on 5 continents and in three different cities in the Bay Area. Most importantly, The Sequences gave the community a common language to talk about rationality. Like the tribe who can’t tell quantities apart because they have no words for counting numbers, learning rationality would be almost impossible without the vocabulary.

I don’t know how I could explain why donating to basic income charity shouldn’t be compared in the framework of buying happiness if I hadn’t heard of fuzzies and utilons. In fact, I probably wouldn’t have even understood it myself. On the other hand, I spent extra time looking for possible negative consequences of basic income because I felt that I was in danger of falling into a happy death spiral around a cool idea. I found myself supporting basic income more after reading arguments that BIG reduces employment, because all these arguments are stupid. I had to remind myself that reversed stupidity isn’t intelligence: a bad argument against BIG doesn’t make BIG a better policy. I read a sophisticated argument with many steps explaining how BIG will reduce taxes in the US if it was implemented, and dismissed it as well. It seemed like a clear case of writing the bottom line first to support an apparent one-sided policy, and the multitude of necessary steps was clearly vulnerable to the conjunction fallacy.

I don’t even remember how it was possible to think about complicated things like economic policy without rationality training. I probably wasn’t thinking much at all, just falling in step with the correct blue/green position. If you asked me now whether I think BIG will increase the quality of life for Americans compared to the current welfare system I would say “75% yes, subject to appropriate updates after the research results are in”. Can you imagine a policy maker giving an answer like that? And yet any answer on such a complex topic that’s not in the form of a probability between 0 and 1 strikes me now as utter insanity. Browsing through my Facebook history, I’m embarrassed by 90% of the “political” views I held before discovering rationality. Not because they’re all wrong, but because I held and proclaimed them for embarrassing reasons.

I hope that all the examples I have given so far seem like simple common sense. Why do we need to go to all this trouble of learning about Bayesian probability and decision heuristics and the rest? I’ll let Scott explain:

I think Bayesianism is a genuine epistemology and that the only reason this isn’t obvious is that it’s a really good epistemology, so good that it’s hard to remember that other people don’t have it.

…

Probability theory in general, and Bayesianism in particular, provide a coherent philosophical foundation for not being an idiot.

Now in general, people don’t need coherent philosophical foundations for anything they do. They don’t need grammar to speak a language, they don’t need classical physics to hit a baseball, and they don’t need probability theory to make good decisions. This is why I find all the “But probability theory isn’t that useful in everyday life!” complaining so vacuous.

“Everyday life” means “inside your comfort zone”. You don’t need theory inside your comfort zone, because you already navigate it effortlessly. But sometimes you find that the inside of your comfort zone isn’t so comfortable after all (my go-to grammatical example is answering the phone “Scott? Yes, this is him.”) Other times you want to leave your comfort zone, by for example speaking a foreign language or creating a conlang.

When David says that [inferring the existence/nonexistence of God from evidence] doesn’t count because it’s an edge case, I respond that it’s exactly the sort of thing that should count because it’s people trying to actually think about an issue outside their comfort zone which they can’t handle on intuition alone. It turns out when most people try this they fail miserably. If you are the sort of person who likes to deal with complicated philosophical problems outside the comfortable area where you can rely on instinct – and politics, religion, philosophy, and charity all fall in that area – then it’s really nice to have an epistemology that doesn’t suck.

I’ll go even further than that: people make dumb, costly mistakes inside their apparent comfort zone all the time. I see people stuck in jobs they hate because their brain is too lazy to snap out of a false dilemma. In these jobs they work on projects that fall to planning fallacies and sunk cost bias, if they manage at all to overcome procrastination and akrasia and do anything. They then spend the money they earned on purchases that make them unhappy. They get into brainless arguments, fail to explain or understand ideas, repeat empty words that mean nothing as if they were deep wisdom, and find solace in ignorance.

If you’re cool with all of that then you probably shouldn’t waste your time with this book.

Post-Rationality: Almost as Good as Rationality

Ok, so the on the plus side, Rationality is an epistemology and a community dedicated to thinking better and achieving goals strategically. On the minus side, it’s an aspiration and not a state that’s actually attainable. There’s a reason why the community hub is lesswrong.com (currently being rebooted to fit the evolving community) and not perfectwisdominfoureasysteps.com (besides the fact that shorter domain names are better).

It makes sense that some people will embrace Rationality and study it. It makes sense that most people will say “Nah, I’m cool” and stick with their old philosophies – that’s the human default behavior. What I’m confused by is people who are part of the broader rationality community who say “Been there, done that. I figured out this rationality thing and moved on to something better now.” Let’s see what they don’t like about Rationality.

In a post called Postrationality, a Table of Contents Yearly Cider writes:

Rationality tends to give advice like “ignore your intuitions/feelings, and rely on conscious reasoning and explicit calculation”. Postrationality, on the other hand, says “actually, intuitions and feelings are really important, let’s see if we can work with them instead of against them”.

For instance, rationalists really like Kahneman’s System 1/System 2 model of the mind. In this model, System 1 is basically intuition, and System 2 is basically analytical reasoning. Furthermore, System 1 is fast, while System 2 is slow. I’ll describe this model in more detail in the next post, but basically, rationalists tend to see System 1 as a necessary evil: it’s inaccurate and biased, but it’s fast, and if you want to get all your reasoning done in time, you’ll just have to use the fast but crappy system. But for really important decisions, you should always use System 2. Actually, you should try to write out your probabilities explicitly and use those in your calculations; that is the best strategy for decision-making.

YC doesn’t cite specific examples of rationalists doing this, so we’ll look to the common base of Rationality, The Sequences, for an answer. Fortunately, The Sequences dispelled the above criticism seven years before it was written:

When people think of “emotion” and “rationality” as opposed, I suspect that they are really thinking of System 1 and System 2—fast perceptual judgments versus slow deliberative judgments. Deliberative judgments aren’t always true, and perceptual judgments aren’t always false; so it is very important to distinguish that dichotomy from “rationality”. Both systems can serve the goal of truth, or defeat it, according to how they are used.

RibbonFarm seems to have been labeled “postrationalist” based on this guest post by Sarah Perry. The only criticism of Rationality in it seems to be that it rejects the value of ritual. For what it’s worth, there are both made up rituals in The Sequences and actual rituals for the community.

Warg Franklin seems to argue that Rationality is near enough to impossible as to be a waste of time, and that common sense and tradition are better guidelines:

Some rationalists have a reductionistic and mechanistic theory of mind. They see the mind made up of a patchwork of domain-specific biased heuristic algorithms which can be individually outsmarted and hacked for “debiasing”. While the mind is ultimately a reducible machine, it is complex, poorly understood, very clever, and designed to work as a purposeful whole. You generally can’t outsmart your mind. It is therefore better to treat the mind as a holistic and teleological black box system, and deal with it on its own terms; experience, intuitively understandable evidence, good ideas and arguments, and actual incentives. The mind is already well-tuned by evolution, and can only become wiser with lots of specific knowledge and experience, rather than more rational with a few high-impact cognitive hacks.

We can’t really replace common sense and intuition as the basis of reasoning. Attempts to virtualize more “correct” principles of reasoning from math and cognitive science in explicit deliberative reasoning are unrealistic folly. We can learn useful metaphors from theory, and use mathematical tools, but theory cannot be the ultimate foundation of our cognition; practical reasoning is either based on reasonable common sense, or bogus.

There are good points here, but not nearly enough to condemn the pursuit of Rationality as useless. Yes, we know that Rationality is very hard, but there’s a guideline to doing impossible things as well. We know that the brain has been finely tuned by ages of evolution, but evolution is neither maximally-efficient nor aligned with the things we care about as humans.

Finally, rationality aims to extend common sense and not contradict it, except in the face of some problems against which common sense and intuition are powerless. While writing The Sequences Eliezer was (and still is) trying to develop mathematical frameworks for a superintelligent AI that will also fulfill human values. That’s pretty hard, since human values are a miniscule region in the universe of possible goals an AI may pursue. As a species, we may only have one shot to solve this problem and without extreme rationality it’s completely intractable.

Eliezer may not be sure that rationality is learnable by people who don’t dedicate their lives to a world-saving mission, but it doesn’t feel unattainable to me. I think that rationality in the service of making better soap buying decisions is still better than stupidity. With that said, I’ll probably donate more money to MIRI this year than I’ll spend on soap, rationality does have a tendency to light a world-saving spark in people.

Bayesless Slander

Our tour of “postrationality” starts and ends with David Chapman:

[1] In pop Bayesianism, the Rule is evidently not arithmetic; it is the sacred symbol of Rationality…Occasions in which you can actually apply the formula are rare. Instead, it’s a sort of holy metaphor, or religious talisman. You bow down to it to show your respect for Rationality and membership in the Bayesian religion.

[2] Maybe Bayesianism is like acupuncture. It has little practical value, and its elaborate theoretical framework is nonsense; but it’s mostly harmless, and it makes people feel better about themselves, so it’s good on balance.

[3] This seems to be the case for Bayesianism also. Leaders pepper their writing with allusions to the obscure metaphysics and math, which are only vaguely related to their actual conduct of reasoning.

[4] It is widely noted that Bayesianism operates as a quasi-religious cult. This is not just my personal hobby-horse.

At this point Chapman notices this quote by Eliezer:

[Eliezer]: Let’s get it out of our systems: Bayes Bayes Bayes Bayes Bayes Bayes Bayes Bayes Bayes… The sacred syllable is meaningless, except insofar as it tells someone to apply math.

And apparently fails at reading comprehension:

[Chapman]: Right. So why doesn’t he get it out his system? Here he’s the one calling it a “sacred syllable.” Apparently he’s aware of the quasi-religious nature of what he’s doing. What’s up with that?

Who are these misguided Bayesian zealots? Did the people who accuse rationalists of being a quasi-religious cult talk to a single person who has read The Sequences? Does Champan really think that when Eliezer says “don’t be a cult, just do math” he really means “be a cult”? We’ll never know, because when Scott rebutted Chapman’s straw version of Bayesianism, Chapman suddenly turned and wrote:

It’s because I find so much right with LessWrong, and that I admire its aims so much, that I’m so frustrated with its limitations and (seeming) errors. I’m afraid my careless expressions of frustration may sometimes offend. They may also baffle, because I haven’t actually offered a substantive critique (or even decided whether to do so). I apologize for both.

It’s nice to get an apology, but it would be much nicer if Chapman deleted these quotes from his blog. The very best rationalists are people like Scott, Kaj Sotala and Vaniver who replied on Chapman’s blog with thoughtful, polite discussions of math and epistemology. The only fault I can find with that is that they should have said “Hey David, how about you stop calling Bayesians a religious cult and then we can start talking politely about math and epistemology?”

And no matter how much David Chapman will protest that of course he didn’t mean that Scott, Kaj and Vaniver are cultists, the harm is done. “cult” is the first suggestion when you google “LessWrong”. People mock LessWrong for being obsessed with obscure nerd topics like AI safety and cryonics. Now a super-popular mainstream blogger writes thousands of words about Rationality enlightenment, AI safety and cryonics, while fastidiously avoiding a single mention or link to LessWrong. Journalists who never read a page of The Sequences write pieces making fun of the community, one of these articles is how I discovered the site myself!

Posts like David’s disparage and smear the entire community, and having actual familiarity with the people and The Sequences he should know better. The “Bayesians are a cult” meme contributed to most LessWrongers moving away from the site into their own outlets on the “Rationalist Diaspora”, or dropping out of the discourse altogether. This robs everyone of the common base of insights and language that The Sequences provide and that allow us to share ideas and learn from each other.

Most damagingly, this slander pushes new people and casual readers away from LessWrong, preventing them from discovering a life-changing resource. It’s the reason why I have to spend 1,500 words discussing “postrationalists”, to keep curious readers from googling “LessWrong” and getting a hideously distorted impression.

Rationality helped me find an amazing girlfriend (more on that story later). Rationality gave me the intuition, the analysis skills and the confidence to take not even scientists at their word. Rationality lets me keep my cool and think of bell curves when I’m caught in a culture war. Rationality gave me the wisdom to change the things I can and accept the things I can’t. Rationality inspired me to write the only poem I ever have.

And now you can write bad poems too. Welcome to the Rationality society, may you be less wrong tomorrow than you were today.

Typo: Bayesless Slander: Our tour of “postrationality” starts and ends with David Champan -> Chapman

LikeLike

Counterpoint: the sequences are not well written. Frankly, I’ve tried to read some of them a few times, and I just can’t read anything Eliezer’s written. I enjoy stuff by Yvain though.

That’s not to say I don’t appreciate and participate in the lesswrong community. I was originally drawn to it as a guard against moral relativism, and I enjoy my local meetups and reading Scott’s and Ozy’s and this blog.

I have two points of contention with the community itself. One is the lack of women. I’m not sure how to solve that. The upholding of rationality as one of the most important values pushes women away by itself (at least, it pushed me away). Speaking of rationality implies that emotion is less important (I don’t mean that the community actually thinks that, but that’s what people first hearing of it will think), and the implied rationality/emotion dichotomy has been gendered throughout the history of western philosophy (Aristotle through Kant). Again, I don’t mean that lesswrong people think that, but that that is suggested to outsiders. This idea is what kept me away from engaging for so long. So, I think involving more women is inherently difficulty because of the fear that the community will be sexist. I need to talk about this with the other women at my local meetup next time.

The other thing about the community is I wish it were more intertwined with the humanist community. The Humanist Hub’s mission includes “We use reason and dialogue to determine our highest ethical values, we act on those values with love and compassion, and we help one another evolve as individuals, as we work to improve our world.” which I think is exactly in line with the rationalists’ goals as I understand them. Humanists tend to be less confrontational, so the two groups may have difficulty communicating.

I’m not sure what my points are. I kinda just word-vomited.

LikeLike

That’s funny, I think you made your points quite clear :)

1. Hey, you can’t force yourself to read 1800 pages of writing you don’t like. I know that HPMoR also tends to polarize opinion, some people really enjoy it as a book and some are nauseated by every sentence.

2. Well, the good news is that the percentage of women went up by quite a bit in the last survey. The bad news is that it’s still below 1 in 6. This is a very thorny problem, I think almost everyone’s answer to “Do women inherently have less affinity with rationality?” comes from their political view and not from a rational review of evidence. That answer affects one’s opinion about whether the LW is being particularly unwelcoming beyond just the subject matter. FWIW, I got both my mom and my girlfriend reading Yudkowsky and they like it :)

3. I’m not sure the values are perfectly aligned, and it makes sense to keep some separation. Rationality is at its core is concerned with “what is true?” and humanism with “what is good?”. It sounds like you’re both, do you see any conflicts between the communities?

LikeLike

2. That’s good to hear!

3. I agree the communities should be separated, I’m just surprised there isn’t more crossover. One conflict is humanists in general don’t seem to be as concerned with internal consistency, which is something I care a lot about. Humanists in general I think are not as engaged with the philosophy itself – it’s more like a religion where there isn’t as much pushback on the leaders. I think that’s why humanism is more common, because it’s much easier to engage with/doesn’t require as much effort. Of course, you can get yourself into a debate, it’s just not the default mode, as it is in rationality.

These are conflicts with the communities. Are there conflicts between the goals? Sure, but not a lot. Mostly I think of unethical research e.g. on humans.

LikeLike

Have you been to a Secular Solstice? It’s a great event that really brings together Rationalists and Humanists. I think it’s great if people who like both will work to increase overlap between the two groups.

On the other hand, Humanism is, AFAIK, supposed to be sort of a religion-substitute. As I’ve argued ad nauseam, I think that Rationality has itself been falsely accused of that so many time that some LWers may be a little allergic to the idea.

On the third hand, Effective Altruism seems to be a combination of the best of both (doing good + evidence and math), maybe we should all learn and follow more EA.

LikeLike

I haven’t been, sadly. Should be able to go next year.

I agree that Humanism is a religion-substitute. I started going because I missed going to church (I went every Sunday as a child). I can see how LWers could be put off.

I don’t think EA is quite comparable. EA, in my perception, has a goal (saving lives) and seeks how to achieve that goal most effectively. Humanism is more about determining what is good. Is democracy good? How should we educate people?

LikeLike

Think globally but act locally. Community grow through word-of-mouth. If you want more woman in the LW community and more humanists in the LW community, how about going to a humanist meetup and asking the woman to come to a LW meetup?

I don’t think that mission statements matter a great deal.

LikeLike

1) I am disappointed that only two numbers were put to things in this post even in variable form. Perhaps a probability analysis on whether or not reading The Sequences would help fix that…

2) Maggie: I am only responding to one little portion of your comment. Namely, “the implied rationality/emotion dichotomy.” I am criticizing the alleged incompatibility and don’t know for sure if you’re referring to the same thing I will be. I apologize if I misread your comment and I want to make sure I’m not passing judgment on the rest of its content except to say that it’s nice to see the similarity in reading habits. The only real connection I have to the rationalist community is through the same three blogs you mentioned (I am ignorant on any Rationalist meetups in the DC area). As far as the alleged dichotomy as an explanation for the gender disparity of the Rationalist community, anything I could say on that issue would be ignorant idle speculation and there is no value for me to engage in such here.

3) As a disclosure, I have not read The Sequences and don’t consider myself a rationalist. I embrace my status as an irrational creature and seek to turn my ignorance into strength. I don’t know whether these things are consistent with the philosophy held by the Rationalist community but based on next to no understanding of such, I would not be able to make a statement on how likely that is. I just tried to put a number to this and couldn’t leading me to make a more accurate statement. Thank you putanumonit!

4) Now the meat of my comment:

One of the things that annoys me a lot about our culture (specifically USA American culture: I cannot comment on other cultures) is the belief that emotional maturity and logical reasoning ability are incompatible. There are numerous examples of this trope and from what I see it is ingrained in our culture and is a belief that people have without ever considering it or even considering whether it is something that should be considered.

I am someone who is very passionate and who has worked hard to develop sound reasoning abilities including skill at both formal and informal logic. In the way my mind works, the two complement each other.

Logic enhances my emotions. It gives me tools to understand the emotions I am feeling and also gives me tools to better seek out other emotions to feel. It’s not that I never experience unpleasant emotions (these emotions are still important to experience) but I understand the balance and have a greater ability to affect my emotions then I would if my reasoning ability were less. I am also better able to relate to the emotions of myself others through having emotional maturity and the skilled use of logic.

Emotions enhance my reasoning ability. Logic itself does not tell one whether a conclusion is true or not; logic conditions the truth of a conclusion on the truth of the premises. A line of reasoning that is logically correct is one that if the premises and assumptions are correct then the conclusion is correct. Logical reasoning does not say anything about the conclusion if the premises or assumptions are wrong. “If it is raining, the tree will get wet,” is a sound logical argument but doesn’t say anything about whether or not the tree is getting wet without knowing if it is raining. When it is not raining, the tree could remain dry or it could be getting wet through another process (somebody is painting it, for example). All it says is that it is impossible for the tree to remain dry when it is raining. Logic by itself doesn’t lead to correct knowledge; it just tells you what outputs must be true given inputs which may or may not be correct. It is quite a valuable skill but it makes having good inputs important. Heuristic reasoning and probabilistic logic are more complicated but, in general, share the same principle.

If I want to make decisions, take actions, and have thoughts that benefit me and those I care about then understanding emotions is quite an asset in doing so. The better my reasoning ability the better I am able to understand the world around me and to shape what I can to better suit my goals. Emotional maturity provides valuable inputs into understanding other people and myself in using my reasoning to do this analysis. One again, both emotional maturity and logical reasoning ability are needed to do good things.

It is usually clearer to others that I have skill at logic then it is that I am a passionate person. This has, on more than one occasion, led people to stereotype me as a cold unfeeling person and other judgements that go along with that. For example that I am willing to act deviously in order to advance arbitrary goals I have chosen unattached from the effects on other people’s emotional states. They have then insisted on acting towards me in accordance with this judgment. This has not always been pleasant.

I don’t know if for most people, emotional maturity and logical reasoning ability are mutually exclusive developmental goals or if most people just find themselves for whatever reason developing one and not the other that they assume that they are mutually exclusive developmental goals or if such attitudes persist through cultural education. I think it is likely for there to be a positive feedback mechanism between the two. I do know that it is possible for at-least some individuals to develop both (as well as it being possible for some individual to never develop either). The belief that at-least some people have that such is impossible has caused me harm and this I am vehemently opposed to the belief.

I don’t know much about stoicism and I have attempted to figure out what actual stoics think about emotions. I get different answers from different sources which leads me to believe that stoics disagree on the subject. One thing that is common is that stoics seek to have mastery of and control their emotional states (though to what ends may be different) and use logic as an important tool in doing so. The popular idea is that stoics are against emotion but the reality is more nuanced. I also, from what I’ve read and what I know about people, believe that this caricature existed in antiquity. If so then the false belief I have been referencing is ancient.

Modern literature has not been lenient in popularizing this belief as can be seen in Vulcans or cold heartless robots. I’m sure there are non-science-fiction examples but why would anybody need those? While I often enjoy fiction that has these elements, I do not enjoy these elements themselves. Why anybody would take the perspective of tv writers, who are experts in neither philosophy nor logic, as what it means to be skilled in logic is beyond me but it is unfortunate.

I have ranted long about a personal gripe. I don’t know who else shares it but hopefully somebody who reads it will get something of value out of it. If this was inappropriate to comment in this situation in these circumstances, I apologize. I also don’t mean to comment on what anyone else has said here in any matter unrelated to the compatibility of emotional maturity and reasoning ability.

LikeLike

1) I’m very disappointed as well by the lack of numbers put on things in this post. This will be over-corrected in the next one.

2) Rationality borrows a lot from stoicism, with two main goals. One – to make sure that you’re making good decisions even when feeling strong emotions. Two – to direct your life towards feeling more good emotions and less bad ones.

For example, there’s was stoicism class in my CFAR workshop, an example stoic technique was visualizing your car being stolen and your actions as you’re walking towards the parking lot. This achieves both goals: if your car is in fact stolen, you will react better because you “practiced” beforehand and aren’t overwhelmed by the anger and sadness. If your car isn’t stolen, you feel a rush of joy, relief, and appreciation for owning a car – you just turned a mundane occurrence into a happy event.

3) Whether you call yourself a rationalist or not, it sounds like you’re pursuing very similar self-improvement goals (emotional maturity, logical reasoning, effective decisions) to rationalists.

If you’re practicing this self improvement using good resources, would you share what they are?

If you haven’t found any existing resources to be outstanding, want to give The Sequences a whirl?

LikeLike

1) Now I’m excited and can’t wait. My cortisol levels must be spiking (in discrete jumps of 3 μg/dl).

2) To be clear I’m not a stoic either. My understanding of stoicism is that in includes an attempt to control emotions. My goal is to rather experience emotions while understanding my experiences and to influence what emotions I experience. I am making an important semantic distinction between control over emotions and influence over emotions. I don’t know enough about rationalism or even stoicism for sure to know how relevant this distinction is in these philosophies but I see an important distinction.

3) You mean good recourses besides Slate Star Codex, Thing of Things, and Put a Number on It? I discovered Slate Star Codex about two years ago and from there found the others. I don’t have a single source for my self-improvement similar to The Sequences and while I could point to specific recourses and techniques, I’ve been working on this nearly my entire life and have used tools from lots of different places some of which are not transferable.

I have been hesitant to reading The Sequences for two reasons. The first is when somebody tells me that reading a thing or doing a thing or thinking a thing will completely and profoundly change my life for the better based on a belief that such is true for everybody, I assume a good chance that I will either find the thing a waste of time or annoying and/or aggravating. I am confident that there are people for whom reading the sequences is of great benefit and there are people for whom reading the sequences can lead to harm. Seeing how the promise of reading The Sequences is to improve my ability and tendency for rational thought and given my high opinion of myself in these areas, I am leaning towards reading the Sequences to be a waste of time and I would end up annoyed that I read 1800 pages to tell me things I already know and do (it’s all obvious in retrospect after all).

The second reason is that having such a high opinion of my abilities at rational thought, I relish testing my abilities with self-described rationalists. If I read The Sequences, I won’t lose this ability completely, but I will lose something. I will no longer be able to test my rational abilities absent reading The Sequences with rationalists. While this hasn’t happened yet, it might, and I will lose that opportunity if I read The Sequences.

As far as deciding whether or not to give The Sequences a whirl, I shall do what I suggested and come up with a probability of whether or not I will benefit from reading them. Consistent with the philosophy of this blog the numbers I use will likely be of poor quality but I will likely come up with a better number then the number I would come up with before any analysis.

Also, I do uncertainty analysis in coming up with my chances. While I suspect that none of the numbers I use have normally distributed probability distributions and I’m positive some of them don’t, I treat all of them like they do because it is easy to do so. Also I have some awful reasons for some of the uncertainties I assign. This analysis is very sloppy but even sloppy analysis is better than no analysis. The goal isn’t to come up with the best number but just to come up with a number following the principles that 1) having a number is better than not having a number and 2) the number will be better the more steps are done to arrive at it even if the base numbers aren’t very good.

Two last disclaimers. The bellow analysis is specific to me. I have speculated on some possible benefits and costs that fit myself. These are necessarily speculative. I won’t know what the costs and benefits of reading The Sequences are until and if I read them. Since I am doing this analysis to figure out if I need to read them I am necessarily working from a sub-optimal perspective. I am also doing an analysis to which I am accustomed. If you do something similar, you might want to use my analysis as a template and make changes relevant to yourself or you might want to create your own method that bests fits your situation and abilities.

The last one: last time I tried using html’s “math” tag in the comments to this blog it didn’t work. I don’t blame Jacob for this but it is still somewhat aggravating. I will test the tag now: a^2+b^2=c^2 and write out my math as best I can Finally, as a standard for decision making, if the chances that reading The Sequences is close to 0% then I will not read it, if it is close to 100% then I will, and if it is close to 50% then I will continue to use other methods of making the determination.

As far as benefits, I can get a direct benefit out of reading The Sequences. There are two ways I see getting this benefit: from the way The Sequences intend in that its advice improves my life and from learning how other people think which is something that I’m very interested in. I can also benefit from the chances of reading The Sequences leading me to have more positive community interaction with a community.

There are similarly two costs I will consider. There is the direct cost of the time and effort spent reading The Sequences. I will adjust this time to consider my concern that I will be annoyed by having read it which would apply costs above and beyond those ordinarily associated with reading. There are also opportunity costs associated with giving up the above ability to test my non Sequenced rationality against Sequenced rationality.

I will deal with the costs first as that includes a relatively straight forward calculation: figuring out how long it will take me to read The Sequances. The Sequences are stated to be 1800 pages which I will convert to 1800 +- 50 pages. After searching the internet for an answer I will assume that each page has 350 +- 50 words per page for a total of word count of The Sequences of 630,000 +- 90,000 words.

I read Worm (Trigger Warnings: Everything) over the month of December. The length of Worm is given as about 1,680,000 words which I will convert to 1,680,000 +- 5000 words. I can’t remember exactly when I started reading Worm and when I stopped nor the average time each day I spent reading it. I’m a binge reader and there were days where I would wake up in the worming (this was initially a typo for morning but I’ve decided to keep it), begin reading, take one meal break, and read until going to sleep that night. There are also other days where I didn’t ready any of it. Based on my vague memories, I will call this 7 +- 2 hours per day over 25 +-5 days for 180 +- 60 hours to read Worm. This yields a reading rate of 10,000 +- 3000 words per hour. Using the cumulative distribution function for the normal function this leads to a .21% chance that I read so quickly that I’ve already read something by the time I start to read it. Perhaps these numbers aren’t normally distributed…

Now The Sequences seems to be a drier and more technical piece of writing then a work of fiction leading me to believe that I will read The Sequences slower than it took me to read Worm but it is also not as likely to be emotionally draining leading me to believe I will read The Sequences faster than it took me to read Worm. In order to have a number to work with I will assume that I will read The Sequences at the same rate that I read Wrom. Given this it should take me 66 +- 25 hours to read The Sequences. As I don’t have as much free time now as I did in December, it is unlikely that I will read The Sequences as voraciously as I read Worm but if I did, it would take me 9 +- 4 days to read The Sequences for a 1.7% chance that I’ve done so already. While this might be true (in that I’ve read everything in The Sequences elsewhere, not all together, and in a different format) this further underscores how sloppy this analysis is.

If reading The Sequences ends up being annoying then I should increase this time to get the true costs, on the other hand, if reading The Sequences ends up being entertaining then I should decrease this cost. I will give reading The Sequences a 60% chance of being annoying and a 15% chance of being entertaining for a 25% chance of being natural. If reading The Sequences is annoying, I will double the cost of reading them for a cost of 130 +- 50 hours and if it is entertaining I will reduce the cost by a third for a cost of 44 +- 17 hours. Needless to say, if it is natural, I will use the unadjusted cost. Taking the weighted average gives me a direct cost of reading the Sequences of100 +- 30 hours.

Now I need the opportunity costs of forgoing pitting my current rationality against rationalists. I estimate that I could spend 10 +-5 hours each year doing this. This gives me a 2.3% chance each year of this value being negative perhaps representing the chance that I have this interaction but I don’t enjoy it. But I need to discount this figure over the course of my lifetime to compensate for the fact that as the years pass (though forgetfulness, through increasing senility, through value drift, and other factors) this cost becomes less and less. I will assume that year to year the cost decreases by 5%. Assuming that I live 50 more years, the discounting factor would thus be (the integral over t between 0 and 50 of .95^t which is about 18). This means that over the course of my life, I would have spent 180 +- 90 hours doing this. Since I value arguing with rationalists more then I value not having to read something, I will multiply this by 5 to get this cost in the same scale as the previous cost so the cost of giving up this ability over the course of my lifetime is 900 +- 400 hours. I should point out that the apparent error is a rounding error that I am controlling for through doing the calculations at a higher precision than I am reporting them.

The opportunity costs of giving up the desired test with other rationalists seam to dominate the costs. Adding these two costs together gives a total cost to me of reading The Sequances of 1000 +- 500 hours. This gives a 1.3% chance that the costs are negative; that is that the mechanisms that I would expect to impose costs actually impose benefits which could be the case as described above.

On the benefits side I need to figure out how likely it is that I get direct benefit from reading The Sequences. One each page I will estimate that I have a 75% chance of learning nothing (this is both in learning tools The Sequences seeks to teach and learning to apply them as well in learning about how people think), a 25% chance of learning a little bit and a 5% chance of learning a lot. Keep in mind these figures are based on my estimation on my current skill at rationality compared with what skill I would have after reading The Sequances. This equates to learning a little bit on 1 out of every 4 pages and learning a lot on 1 out of every 20 pages.

I will estimate that if I learn a little bit based on the information of a single page then I will have 10 minutes of benefit each year. This is on the same scale I have for the costs of reading (this means that 10 minutes of benefit is equivalent to 10 minutes of not having to read anything). Furthermore if I learn a lot on a single page then I estimate then I will have 2 hours of benefit each year for total lifetime benefits (given the same discounting factor which measures essentially the same thing) of 3.0 hours and 36 hours respectively. Of course if I don’t benefit at all this translates into no benefits.

Taking the weighted average, I should have an average of 2.5 hours of lifetime benefit on each page of The Sequences that I read. I need to assign an uncertainty to it and I will convert this to 2.5 +- 1.0 hours which gives a .62% chance that what I read on a page does me more harm than good. I chose this uncertainty precisely to have small but noticeable chance of this happening. Given this and multiplying by the number of pages I come up with a total direct benefit of reading The Sequences of 4600 +- 1800 hours. This is a lot more than the total cost so without doing any further analysis one should already know what my answer is going to be but I shall continue.

I need to put a number on how much I would benefit from increased interpersonal interaction I would have from reading the sequences. I think a good upper limit to this is 24 hours each year but there should also be a non-trivial chance that I would find this increased interaction more unpleasant then pleasant. I know myself and I know that there are groups that I really don’t fit in well with. Controlling for these two I come up with a value of 15 +- 11 hours each year of benefit from this increased interaction. This gives a 21% chance that this number is grater than 24 hours and a 8.6% chance this number is less than 0.

Multiplying this figure by my discounting factor gives a total lifetime benefit from increased interpersonal interaction at 270 +- 20 hours. I enjoy interpersonal interaction more then I dislike reading but I also get some enjoyment over being ornery (relevant for the factor of 5 for testing myself against rationalists) so I will multiply this figure by 4 so that I can compare it with the time it takes me to read The Sequences. This makes the value of this benefit to be 1100 +- 800 hours. This is notably smaller than the direct benefits of what I will learn reading The Sequances.

Adding these benefits together yields a total expected benefit from reading The Sequances to be 5700 +- 2000 hours. This gives a .23% chance that the potential benefits actually end up costing me more than they benefit me.

Taking the benefits and subtracting the costs gives a total expected net benefit for Ben Schwab reading The Sequances of 4700 +- 2100 hours. This figure has a 98.9% chance of being positive. Welp, I guess I’m going to be reading The Sequences. I will still wait a few days before trying it out as I am doing a creative project right now and I don’t want to do something that will significantly change my mindset for this project.

Numbers are fun! Also, I hope I didn’t make any significant errors in the formatting…

LikeLike

It’s me again! I’m in the process of reading the sequences (about 20% through) and actually enjoying them. I now find the snark amusing instead of annoying. So, I recommend to others 👍

LikeLike

>Fortunately, The Sequences dispelled the above criticism seven years before it was written:

I believe your “dispelling” of the argument is incorrect and very similar to [Motte and bailey doctrine](http://slatestarcodex.com/2014/07/07/social-justice-and-words-words-words/). I as a reader of LessWrong and other LessWrong diaspora blogs notice that lesswrongers pay too much attention to the ways we can think about things with our thinking mind (System 2). It seems more important to me to modify our System 1 instincts or whatever you call them, because that’s what we use more than 90% of time.

In theory rationality is about winning, but on practice that’s not what lesswrong rationalists optimize for. First of all we’re a bunch of nerds who like to discuss science, epistemology, AI instead of finding useful lifetips to help us change bad habits of our System 1.

LikeLike

Yeah, there are thousands of rationalists, each with their own goals, some more “rational” than others. I didn’t want to get into “no true Scotsman” arguments (does a “true” rationalist only comment on blogs?), so I brought everything back to what’s in the Sequences as the thing I identify as “rationality”. My goal is to get people who resonate with the ideas of rationality to read the Sequences, whatever they choose to do with it and whichever rationalists they choose to hang out with is not for me to say.

Also, motte and bailey is about jumping between explicit and implicit positions, not about people’s adherence to positions that someone else wrote. If the Sequences said “emotion is sometimes nice” that would be a motte if the bailey was “we don’t think system 1 is an evil to be overcome”. But the Sequences actually talk about system 1 and system 2 explicitly, not trying to trick anyone. That quote is literally the first result for searching for “system 1” on LW.

If the Sequences gave advice that was impossible to follow, the criticism would be that they are too hard to be useful (what Warg wrote), not that they are dishonest. Personally, a lot of my rationality progress has been about improving system 1, for example intuitively smelling misleading charts, iffy science and bad purchases.

LikeLike

Ahen I wrote “lesswrongers pay too much attention to …” I didnt mean to separate the diaspora into lesswrongers and others. By saying lesswrongers I meant all of them – basically all the rationalists, except I decided I dont want to use the word “rationalist” after reading some articles you linked 😀

So, it seems to me that motte is what rationalists actually discuss, write and do – that is too not enough stuff about intuitions and changing system 1 habits. The bailey is We’re rationalists, our website says rationality is about winning and here we actually write that system 1 is important too.

LikeLike

OK, I still don’t think that attitudes towards system 1 are something that cleanly separates people into rationalists and postrationalists as YC implied. If you personally think that most people underappreciate system 1 that’s a fair point, but also arguable. If you train rationality to buy better soap, training system 1 is helpful. If you’re developing AI decision theory, maybe it isn’t. And again, did you survey all the rationalists about their system 1 attitudes? We both have limited data.

My point about the motte and bailey is that I’m pretty sure that Eliezer didn’t think “I’ll write here that system 1 can help guide us to the truth but that’s actually a lie and I’ll encourage everyone privately to fight system 1 as an evil enemy”.

LikeLike

Oh, I have almost no idea what postrationality is actually about. I used to think that postrationality is essentially the same rationality, but for some reason people decided to form their own tribe and have slightly different values. But now that I’ve read Postrationality. Table of Contents https://yearlycider.wordpress.com/2014/09/19/postrationality-table-of-contents/, and it says they are into magic and spirituality, I don’t think so anymore.

And knowing that, I am not even sure if the original argument about intuition vs system 2 had the same meaning as I used.

Btw I don’t think Eliezer did that intentionally either, but I also think that most people who actually use motte-and-bailey don’t do so intentionally.

LikeLike

For another data point, Rationality probably helped me get along with my emotional side. I noticed that my System 1 does stupid shit with an annoying regularity way before I read the Sequences (or Thinking Fast And Slow, for that matter), but my previous “solution” was basically that System 2 led a mutiny in my brain and locked System 1 in the brig – which, I can attest you, is not a very healthy state of affairs.

Now that I know why System 1 did all the stupid shit, I can finally make peace with it and try to train it into being more useful. It still tries to do a lot of stupid shit when I let it out, but I’m getting better at anticipating and guiding it, and I don’t need constant vigilance because I have a better idea when it can do an OK job by itself.

In comparison, the Sequences didn’t do that much for my logical side. The most important contribution was probably all the jargon that helps with articulating thoughts. Though some of these concepts are also really good at putting red flags up when thoughts are about to go wrong (Conservation of Expected Evidence and Mysterious Answers come to mind here).

I also did occasionally use Bayes’ Theorem in Fermi estimates (e.g. to figure out how to weigh inconclusive evidence in a court case that smelled wrong to me), but I’d call that a fringe benefit. Going through the numbers mostly keeps your intuition from mixing up P(B|A) and P(A|B) or similar mistakes – but a well-trained intuition might get better at that even without knowing any math.

LikeLiked by 1 person

>slightly miffed at “postrationalists” on my blog

To me it seems like you try to argue that people are bad without trying to coherently address their positions.

You blame Chapman&Postrationalists for creating a public perception of LW being a cult. Historically I don’t see that link. Those are mostly attacks that come from another front and generally people who think LW doesn’t adhere enough to the establishment view. Mainly RationalWiki and a certain individual who shall not be named due to the truce.

You use religious framing for this movement yourself while criticizing others for doing so. If your goal is not to be seen as a cult, what better way to do it then to write a post which has a headline that speaks of a “secret society”.

> But the answer is that there isn’t anything wrong with The Sequences, and they successfully anticipated 9 years ago basically every challenge thrown at them since

I think Chapman has convincily argued that probability has not been proven to be a superset of logic (predicate calculus) as EY claims in the sequences. He has written AI algorithms (on which he published papers) that use logic but don’t Bayes theorem, therefore EY claim that he knows that any AGI has to be based on Bayes theorem is not established.

More fundamentally saying “they successfully anticipated 9 years ago basically every challenge thrown at them since” is a claim that there wasn’t substantial updating after the first proclamation of text. That’s something typical for religion. It shouldn’t really be typical for a community that prides itself on updating.

I don’t think that’s actually the case and that various people in this community have changed their minds in the last 9 years but writing the sentence like that still signals the wrong values.

EY did say: “Let’s get it out of our systems: Bayes Bayes Bayes Bayes Bayes Bayes Bayes Bayes Bayes… The sacred syllable is meaningless, except insofar as it tells someone to apply math.”

That’s however not how Julia Galef (JG) describe it in the video. JG does admit that she often doesn’t use the math of Bayes theorem but she still claimed she’s doing Bayesianism.

Having a moat towards which one can point doesn’t mean that the reader suffers issues of reading comprehension.

Tetlock writes in his book:

>“ I have a better intuitive grasp of Bayes’ theorem than most people,” he said, “even though if you asked me to write it down from memory I’d probably fail.” Minto is a Bayesian who does not use Bayes’ theorem. That paradoxical description applies to most superforecasters.

If the only point of Bayes rule is to get people to use math Minto the superforcaster who thinks of himself as Bayesian is no true Bayesian because he doesn’t use Bayes rule.

I think EY said that the term Bayesianism was in retrospected badly chosen. Today people rather use a phrase like “I’m an aspiring rationalist” when they want to signal personal identity and “applied rationality” as a label for the art.

In general various people in this community moved more in the postrationality direction. I remember statements from EY on Facebook that he doesn’t advocate simply shut-up&calculate but more something like calculate and then listen to what you think makes sense.

CFAR (JG) found out that [emotions](http://lesswrong.com/lw/il3/three_ways_cfar_has_changed_my_view_of_rationality/) are more important than the sequences suggest.

LikeLike

Wait, did you miss the part where I make an alluded comparison between Eliezer and Jesus? I write tongue in cheek most of the time, I’m fully aware that much of my humor will miss many of my readers. That’s actually a reason why I started my own blog instead of writing mostly on LW. If my style is confusing, I apologize.

Yes, that’s the entire point! He’s a Bayesian in my book and in Eliezer’s book too, which explains over and over that you do Bayes-like stuff whenever you make true conclusions from evidence even if you don’t do this explicitly. I have no idea why this makes certain people hallucinate an army of robed cultists running around and applying the explicit Bayes’ formula to figure out if the sun will rise tomorrow.

Most attacks are by clueless outsiders, people are always happy to gang up on a niche group with esoteric interests. They’re not reading Putanumonit either. But Chapman is an insider: he is familiar with LW and involved in the community. Maybe what he wrote isn’t very harmful compared to others, but he may actually understand why it’s harmful and correct it.

Thank you for sharing the link to Julia’s excellent post. To me, she stands is in sharp contrast to Chapman and others. She writes on LW itself, and never calls herself a “postrationalist” or imply that The Sequences are old news and she’s “over it”. She notes the common ground between CFAR and LW and writes how she used The Sequences as a base to develop her own art of rationality that is useful for her own purposes. That’s literally what The Sequences implore people to do and the noble pursuit of a rationalist. For her troubles, Julia get’s strawwomanned by Chapman as a “pop-Bayesian”.

I’m a CFAR alum myself, I admire Julia and the entire staff and see no clash between The Sequences and CFAR. Sometimes I apply Bayes’ rule, sometimes I do goal factoring, sometimes I train my system 1 to not be tempted to buy new clothes all the time. All of it is rationality, and if you read carefully, almost all of it is in The Sequences.

LikeLike

It would be nice if the blog would parse markup or at least give me an edit button to properly format my post.

LikeLike

You obviously mean markdown

LikeLike

The WordPress platform supports HTML tags, so if you want to post a link you will use something like <a href="… and <blockquote… for quotes. I don't know if I have a way to let commenters edit their comments, I didn't find that option anywhere.

LikeLike

https://rivalvoices.wordpress.com/2014/12/06/you-cant-optimize-anything-literally/

LikeLike

The fact of the matter is, the emphasis on probability theory and Bayesian epistemology is a serious flaw in the sequences,

Yudkowsky definitely made it sound like Bayesian epistemology is a complete account of ‘rationality’, and you continue to see ‘rationalists’ promoting the myth. For instance Scott A just recently posted an essay on his blog entitled ‘It’s Bayes all the way up’.

In fact, Bayesian epistemology is at best around 1/3rd of what constitutes ‘rationality’. There are THREE major classes of reasoning methods: Deduction (symbolic logic), Induction (probability theory) and Abduction (categorization and concept learning). Bayesian epistemology only fully accounts for Induction. So 2/3rd’s of ‘rationality’ is missing from the Bayesian account.

Don’t believe me? Take a look at my ‘Reality Theory Portal’ here, listing 27 core knowledge domains (links to A-Z lists of wiki articles):

http://www.zarzuelazen.com/CoreKnowledgeDomains2.html

‘Rationality’ is represented by the group of 3 knowledge domains listed in the middle-left-hand column (Mathematical Logic, Probability Theory and Concept Logic).

You only need to observe the grand pattern to see that Bayesian epistemology cannot possibly be giving a complete account of rationality, In fact, the pattern seems to suggest that Bayesian Induction is actually just a special account of Abduction (Concept Learning).

LikeLike

I’d like to submit “evolution produced blobfish too” as an error.

The ugliness of the blobfish is an amusing & “sciencey” anecdatum of exactly the sort that rationalists should question & avoid. See here: http://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/in-defense-of-the-blobfish-why-the-worlds-ugliest-animal-isnt-as-ugly-as-you-think-it-is-6676336/?no-ist=

Evolution produced an entirely reasonable fish adapted to the deep ocean; massive decompression (& slanderous decontextualization) produced the blobfish.

LikeLike

It’s refreshing to finally hear someone give The Sequences their due credit. As I’ve been reading them I keep asking myself, why aren’t more people talking about this? And why did I have to randomly stumble upon this work after college in order to learn how to think correctly?

LikeLike

I read this post years ago and was not moved to go read The Sequences — but I stumbled upon it again today, and here I am, starting to read The Sequences. Your continued insistence that rationality is good, actually, seems to have helped wear down my resistance; though Eliezer’s writing goes down like candy for me (I read HPMoR this winter, finally, and hated that I loved it), actually reading it feels unstylish. But, cheers, I guess, to not letting my preconceptions of the aesthetics of rationalism get in the way of… actually seeking the truth and (ugh) winning.

LikeLiked by 1 person