Update 12/10: this post is tagged hedgehog alert because it touches on a touchy politicized subject, and a reader was disappointed that I neglected to include an actual hedgehog pic. My apologies! Here’s a photo of a hedgehog staying cool in the face of global warming, by the world’s most amazing hedgehog photographer, Elena Eremina.

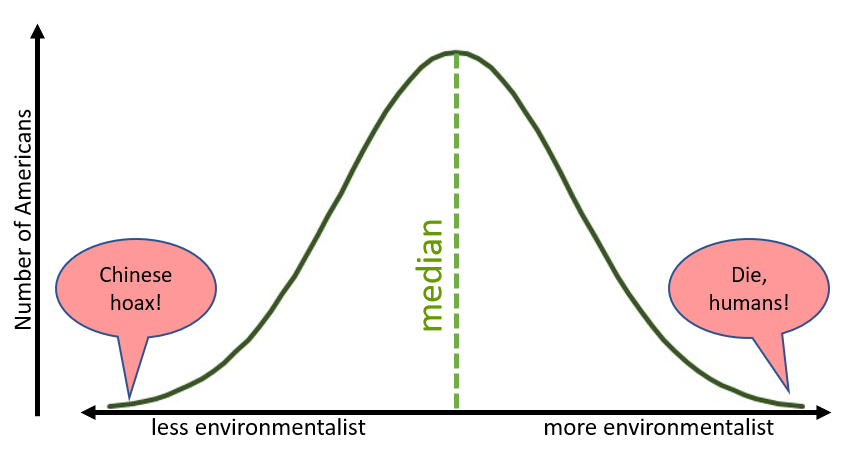

Does the median American worry about climate change too much or not enough? It’s a simple enough question, and yet the distribution of answers to it looks something like this:

This distribution doesn’t strike most people as unusual. But isn’t there something missing here? Let’s try to figure out if Americans worry about climate change way too much or not nearly enough for ourselves.

How can we assess the position of the median/general American on the topic? We could start by looking for a representative sample of Americans’ opinions offered online. Here’s a search for the phrase “global warming” on Twitter:

In general, the opinions seem to be evenly allocated between “It’s a Chinese hoax” and “Humans should just all die” with little in between. Maybe Twitter isn’t the best way to gauge national opinions.

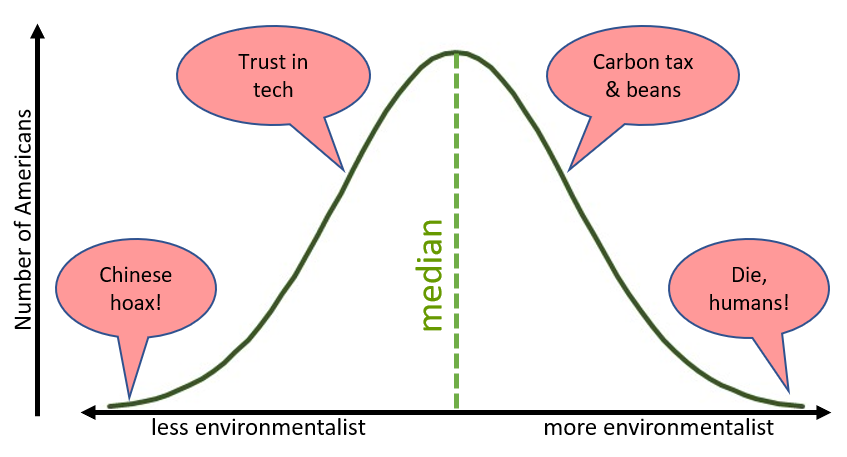

We remember that online visibility is negatively correlated with reasonableness, and that there’s usually a quieter majority in the middle of the bell curve. Our default model should be that the distribution of Americans’ opinions on global warming looks something like this, even if it’s not precisely a bell curve:

Again, our question is whether the median/general/consensus opinion, or more generally the entire curve, is too far to the right or to the left of where it should be given the planet, the economy etc. There are really stupid opinions on both edges. Are there equally smart opinions close to the median on both sides? It seems to me that there are.

I have smart friends who noticed that US emissions peaked over a decade ago and are still falling, and that we already put enough subsidies in renewable energy to set in on a path to economic viability that can’t be much accelerated by more money. They point out that 20% of Indians still don’t have access to electricity. We’ll just have to swallow the emissions cost of hooking them (and Africa and rural China) to the grids and accept a moderate increase in temperatures. They don’t think we can do too much about that increase right now that isn’t prohibitively expensive, and they’re more optimistic about the potential technological solutions to global warming.

I have other smart friends who note that Americans still lead the world in CO2 emissions per capita. They’ll argue that we should do more both personally (like overpaying for solar panels and eating less meat) and collectively (a national carbon tax) to not only bring our emissions in line with the rest of the world but also to lead by example. They’ll point out that even mild increases in temperature can have outsized harms (like the 2017 hurricane season), and that the risk of catastrophic heating is still high enough to demand drastic action.

So the full curve looks something like this:

Now personally, I’m neither an expert on climate science nor incentivized to become one. Senators don’t come to Putanumonit for advice on setting a carbon tax (yet, growth mindset!), and the impact of my personal lifestyle choice on the issue is quite small. As a non-expert, the dumb positions on the extremes of the curve seem equally dumb to me, and the reasonable positions closer to the middle seem equally reasonable. The latter provides much stronger evidence than the former for the median being roughly correct, but those two symmetries tend to show up together.

Of course, things like incentives and availability of knowledge could skew the opinions one way or another. But in this case, on first approximation, the potential skewing factors also appear symmetrical.

Partisan blue-tribers have the same incentive to exaggerate their worries about global warming as partisan red-tribers have to downplay it. Industrialist are incentivized to ignore the danger of climate change and they have money to lobby and advertise, but climate scientists are incentivized to overstate these dangers and they have trust and prestige. Figuring out which side the curve is skewed based on relative incentives and power is probably as tough as figuring it out based on understanding atmosphere physics and trade economics. Both tasks are way above my pay grade.

That leads me to adopt two positions with regards to climate change. The first is a relatively centrist position on the issue itself: I think a moderate carbon tax would be a good idea but we shouldn’t impose one on poor countries, that Teslas and nuclear power plants are cool but obsessing about local tomatoes and light bulb efficiency is silly.

And with regards the original question I raised, the national conversation about climate change and the environment, I’m led to conclude that Americans, on average, are worried roughly the correct amount, and that the conversation is roughly where it needs to be.

I’ve noticed that even people who are relatively OK with my opinion on climate change itself are apoplectic about the second part. How can I not think that on, the issue of climate change, everyone is wrong, crazy, evil, or all three at the same time?

Like I said, I think that a lot of people on the extremes are wrong and crazy (although almost nobody is evil). But they’re not wrong on average, which means that the conversation as a whole can’t be too much improved. Opinion curves can move, but they’re very hard to squeeze. It’s an unavoidable fact that any distribution of opinions will slide into insanity at the edges, and that the gap between the crazies on either side will remain gigantic.

For example, there’s a distribution of opinions about how much a share of Apple Inc. should be worth:

I’ve heard opinions about Apple that are as batshit as anything global-warming Twitter can provide, but they’re about equally batshit on both sides. Closer to the middle, there are good reports by analysts who think Apple should trade around $150 and equally good reports by equally competent analysts who think it should trade around $190. Collectively, we are probably not too far off in figuring out that a share of Apple should be worth close to $169.80, where it trades as of this writing.

There are self-corrective mechanisms that apply to the pricing of stocks that don’t apply to climate change, but the shape of the curve is likely to be the same. This means that I’m much more confident we’re right about Apple than I am that we’re right about climate action, but the location of my opinion is still around the average barring new evidence.

I could have picked 10 topics even more controversial than climate change. Like climate change, they all involve complex trade-offs that distribute suffering and utility. Like climate change, they become politicized and the online conversation about them is terrible. But that doesn’t mean that the average of that conversation is way off.

Not every controversial issue is symmetrical, not every market is efficient, and you may have special knowledge on a subject that makes it clear that the average opinion is way off. But by default, debates shouldn’t appear one-sided because they almost always aren’t.

You shouldn’t be afraid to notice the symmetry of good and bad arguments, the symmetry of knowledge and incentives on both sides, and say: “I think as a society we are roughly in the correct spot on this issue. I shouldn’t be trying to nudge the discussion in either direction, I should probably just shut up and focus on something else.“

It’s a strange thought at first, but liberating once you’ve tried it.

I have so many opinions about this! Maybe my most important disagreement — if, hypothetically, lawmakers were reading the comments of your blog — is that poor countries should absolutely have carbon taxes (and rich countries should simultaneously infuse those countries with cash to make that at least revenue neutral)!

I think carbon taxes are pretty vital and we should all be fighting for them.

I generally agree about almost no one being evil but it’s hard to come up with a definition of evil that excludes the “humans need to just die” people. I mean, even they think they mean well, but, oy.

And yet, in this case maybe they’re pulling the average in the right direction. Which reminds me of this brilliant bit of allegory by Scott Alexander of Slate Star Codex: http://dreev.es/climate (If Climate Change Happened To Have Been Politicized In The Opposite Direction).

So, yeah, it’s incredibly unfortunate that climate change got politicized.

PS: One more relevant Slate Star Codex post: http://slatestarcodex.com/2017/04/17/learning-to-love-scientific-consensus/ — I think it means that, despite not understanding the climate science, we have to assume the so-called climate alarmists are right.

LikeLike

Does the blue tribe actually cause less emissions? New Yorkers drive less but fly more, so who knows.

Anyway, I don’t disagree with what you wrote on the surface. There’s consensus on some issues (that humans cause warming through emissions) but scientists disagree on other important issues, like where it becomes a runaway process, whether aerosols can cool the planet, whether agriculture will improve or worsen etc. I think that the median opinion believes the scientific consensus, and we are already doing a lot about it like having emission standards for cars and power plants.

I would also agree that bribing poor countries could be economically efficient, I just don’t think it’s on the table politically.

Being in the middle doesn’t mean I think we shouldn’t do anything about climate change, just that we shouldn’t drastically increase or decrease the current trajectory of our efforts. It also means that if you live in a bike-friendly city you should keep biking, but not begrudge a rural Midwesterner their car.

LikeLike

I didn’t mean to imply that liberals cause less emissions! And I agree about not begrudging people their transportation choices. (Well, I begrudgingly agree. I personally hate cars sooo much!)

I just think carbon taxes are vital. That might be my only real opinion on climate change. To put it more strongly: carbon taxes are the only solution.

I mean, geo-engineering could be great but we don’t know if it will work so it should be pursued orthogonally. If it does work and mitigates the negative externality of carbon emissions then the carbon tax should fall correspondingly.

PS: Shout-out for Pigouvian taxes in general.

LikeLiked by 1 person

(Haven’t read Scott’s post yet)

I’d posit that that consensus is not the measure by which a non-expert should judge experts. Rather, it should be on the predictive validity of the claims that are made.

Specifically with respect to climate, to what degree do the models have predictive validity?

LikeLike

Assuming you are correct about the distribution of opinions in the USA, I would strongly suspect that the distribution of opinion in the rest of world is centered considerably further towards the climate change is bad end of the scale. If my suspicion is true, either the average American is wrong not to be more concerned about climate change, or the average person globally is wrong to be as concerned as they are.

LikeLike

Good point, but are you sure who’s more concerned? Germans are more environmentally conscious than Americans, but Russians and Japanese are probably less. I wrote ‘Americans’ because that’s what I know, but feel free to replace it with “people in developed countries”.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Again with the false middle argument – that the truth lies exactly evenly between the climate-change-is-bad peer reviewed data, and the China-climate-hoax Fox and friends diatribe. Facts don’t have 2 sides. Except in American political ‘discourse’.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Except he said “my opinion” and “around”, not “the truth” and “exactly”.

LikeLike

Part of the problem is that the distribution of opinions of legislators probably doesn’t match the distribution of opinions of the general population – it seems to me that Congresscritters are more afraid to contradict the highly visible and vocal nut jobs than they are the silent but sane middle.

LikeLike

You’re also forgetting to weigh risk asymmetry – if you’re wrong on one side you’re slightly losing optimal resource allocation, but if you’re wrong on the other side (AKA the side all the scientists are on), you raise the probability of mass extinction by a nontrivial amount.

LikeLiked by 1 person

For some reason, not that many people have noticed that the “scientific consensus” estimates for the Social Cost of Carbon are in the non-hysterical range.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Maybe I should expand on that. The claim by “climate denialists” (based on MSM coverage of climate change) is that the climate change issue is an excuse for a government takeover of the economy. If that were the case, we would see a official estimates of the Social Cost of Carbon in the hysterical range and we don’t.

LikeLike

First, saying “I don’t know much about this but I figure that the ‘average’ must be a pretty good assessment because it seems that way to me even though I just said I don’t know that much” is a ridiculous argument. You can’t make this claim that the somewhere-in-the-middle argument is a good one unless you have more-than-average knowledge of a situation.

Second, the above comment by shakeddown has it spot on. Climate change really is a unique issue because of this asymmetry.

Please, take a little time and educate yourself on the facts around climate change. And this argument has some very substantial consequences for humanity. Yes, there are facts. No, it’s not that hard to find them. Then come back and revisit this.

LikeLike

The big issue I have with your argument is that the real curve in the US doesn’t look like that. If it did I would agree with you; neither of the two “moderate” opinions you mention are unreasonable. But in reality something like a third of Americans flat out do no believe human caused global warming is happening at all. Meanwhile your other extreme (“all humans should die”) is a lot more rare; I don’t know exactly how rare but I’d guess less than 1%.

What we have might be more of a bimodal distribution, I think. There is a whole other curve of people off to the left of your graph who are in some degree of climate change denial, and roughly a third of the population are there. It’s possible you’re not aware of that curve because they’re outside your “bubble” but they exist.

In other words, I think we as a society are not close to the correct spot on this issue, because I think the real opinion graph is very different from what you put in this post. Look up the Gallup or Pew polling on the subject; it looks like the current center is not where you think it is,

LikeLike

In other words, the median voter makes more sense than the modal voters.

LikeLike

I don’t find this particularly compelling. There doesn’t really seem to be an argument here except “extremist views sound dumb to me” and I don’t even agree with that part.

Like, let’s take the ‘humans should all die’ position. I think that rests on the following hypothesis which are incorrect

– An earth with a ‘healthy’ biosphere without humans is net positive value (pretty sure it’s negative)

– There will be singularity (pretty sure will be one)

And perhaps

– voluntarily ceasing to breed is an effective strategy to cause human extinction (there are probably other ways to do this, even without suffering)

So while I’m very confident that the movement is misguided, I don’t have too many problems imagining a very similar universe in which this is a very rational and altruistic idea.

Even on the opposite extreme, I’d agree that the ‘chinese hoax’ in particular is stupid, but ‘scientists are universally not trustworthy’ strikes me as… fairly unreasonable, admittedly, but not, like, incredibly unreasonable.

I think both view points might be -more- rational than being a quarter far on the curve (that is, thinking climate change is real and requires some action but we’re doing too much right now). That strikes me as completely unreasonable.

And in general, reality has no reason to put the truth near the center of an opinion curve.

I also want to point you to this interview with Eliezer Yudkowsky (https://intelligence.org/2016/03/02/john-horgan-interviews-eliezer-yudkowsky/). You strike me as committing a simialr fallacy. Excerpt:

Eliezer: Because you’re trying to forecast empirical facts by psychoanalyzing people. This never works.

Suppose we get to the point where there’s an AI smart enough to do the same kind of work that humans do in making the AI smarter; it can tweak itself, it can do computer science, it can invent new algorithms. It can self-improve. What happens after that — does it become even smarter, see even more improvements, and rapidly gain capability up to some very high limit? Or does nothing much exciting happen?

It could be that, (A), self-improvements of size δ tend to make the AI sufficiently smarter that it can go back and find new potential self-improvements of size k ⋅ δ and that k is greater than one, and this continues for a sufficiently extended regime that there’s a rapid cascade of self-improvements leading up to superintelligence; what I. J. Good called the intelligence explosion. Or it could be that, (B), k is less than one or that all regimes like this are small and don’t lead up to superintelligence, or that superintelligence is impossible, and you get a fizzle instead of an explosion. Which is true, A or B? If you actually built an AI at some particular level of intelligence and it actually tried to do that, something would actually happen out there in the empirical real world, and that event would be determined by background facts about the landscape of algorithms and attainable improvements.

You can’t get solid information about that event by psychoanalyzing people. It’s exactly the sort of thing that Bayes’s Theorem tells us is the equivalent of trying to run a car without fuel. Some people will be escapist regardless of the true values on the hidden variables of computer science, so observing some people being escapist isn’t strong evidence, even if it might make you feel like you want to disaffiliate with a belief or something.

There is a misapprehension, I think, of the nature of rationality, which is to think that it’s rational to believe “there are no closet goblins” because belief in closet goblins is foolish, immature, outdated, the sort of thing that stupid people believe. The true principle is that you go in your closet and look. So that in possible universes where there are closet goblins, you end up believing in closet goblins, and in universes with no closet goblins, you end up disbelieving in closet goblins.

LikeLike