Rabbit fiction is always about rabbits, but science fiction isn’t always about science. The best science fiction, however, usually is. Science fiction transports the reader to strange and novel worlds; figuring out how those worlds work is often as important to the story as resolving the plot. And the best approach we have to figuring out how a world works is, in fact, science.

Harry Potter is a pure fantasy book, but Harry Potter and the Methods of Rationality is very much science fiction. The protagonist of the latter desperately applies the scientific method to understanding Hogwarts, rather than calmly accepting that reality is broken and stuffing his face full of ginger newts.

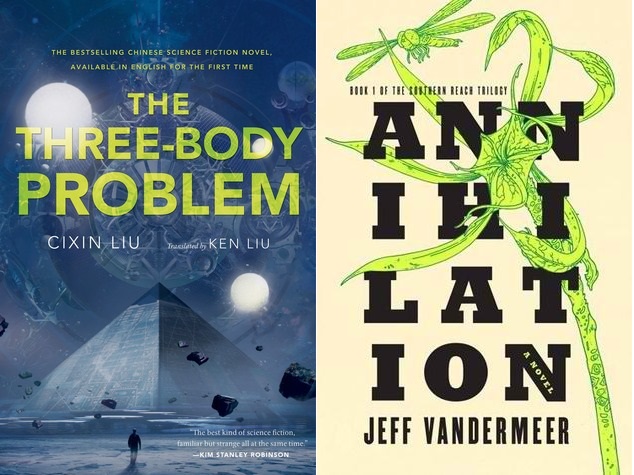

It’s an interesting exercise to categorize science fiction based on the science at the heart of each story. This can be anything from microeconomics, to theoretical computer science, to political philosophy. The two books I want to discuss today: Liu Cixin’s The Three-Body Problem goes with the classic combination of math and astrophysics, and Jeff Vandermeer’s Annihilation is a rare example of ecology fiction.

Both books aren’t leaving the reader to do the science all by themselves, they each are centered around scientist main characters. Three-Body Problem focuses on two Chinese physicists: astrophysicist Ye Wenjie and Wang Miao, a nanotechnology researcher. The main character of Annihilation is “the biologist”, because, well:

There were four of us: a biologist, an anthropologist, a surveyor and a psychologist. I was the biologist. All of us were women this time, chosen as part of the complex set of variables that governed sending the expeditions.

[…]

I would tell you the names of the other three, if it mattered, but only the surveyor would last more than the next day or two.

– Annihilation, page 4.

However, the two books have radically different takes on a core question of what makes a scientist? One of the books’ answers I found deeply unsatisfying, while the other created a memorable character that may have altered my own life more than any work of fiction ever has.

I will quote extensively from both novels but do my best to keep the spoilers light for those who haven’t read the books yet. For clarity, quotes from Annihilation are in teal and from Three-Body in purple.

The classical plot structure of fiction follows a _/\_ shape, like a hike up and down a hill. For example, here’s the plot structure of The Three Little Pigs:

Having done away with conventions like giving the characters names, Annihilation also eschews the traditional plot structure. The reader is dropped straight into “Area X” without much in the way of exposition. This establishes the consistent mood that will carry throughout the book:

The tower, which was not supposed to be there, plunges into the earth in a place just before the black pine forest begins to give way to swamp and then the reeds and wind-gnarled trees of the marsh flats. Beyond the marsh flats and the natural canals lies the ocean and, a little farther down the coast, a derelict lighthouse. All of this part of the country had been abandoned for decades, for reasons that are not easy to relate. Our expedition was the first to enter Area X for more than two years, and much of our predecessors’ equipment had rusted, their tents and sheds little more than husks. Looking out over that untroubled landscape, I do not believe any of us could yet see the threat.

[…]

At first, only I saw it as a tower. I don’t know why the word tower came to me, given that it tunneled into the ground. I could as easily have considered it a bunker or a submerged building. Yet as soon as I saw the staircase, I remember the lighthouse on the coast and had a sudden vision of the last expedition drifting off, one by one, and sometime thereafter the ground shifting in a uniform and preplanned way to leave the lighthouse standing where it had always been but depositing theis underground part of it inland. I saw this in vast and intricate detail as we all stood there, and, looking back, I mark it as the first irrational thought I had once we had reached our destination.

“Area X” is an alien environment. Alien in the sense of being strange and incongruous, rather than necessarily extraterrestrial. The biologist is two things simultaneously: a scientist trying to comprehend an ecosystem that plays by different rules, and an organism trying to adapt to it. From both sides this creates the creeping sensation of something-is-wrong that one usually feels only in NYC pre-schools.

The structure of Annihilation’s plot and its content serve the same purpose, and to great effect. Area X doesn’t leave the characters time to orient themselves; the book doesn’t ease the reader into the plot either. Area X is unpredictable and confusing; the reader shouldn’t count on a telegraphed resolution arriving on schedule at the second beat of the third act of the story.

Area X is just wrong, now deal with it.

Three-Body, on the other hand, is very deliberate about setting up what is going wrong for the Chinese physicists. First, everything that went wrong with China, and then everything that goes wrong with physics. The first third of the book doesn’t even touch on the main plot, but takes place instead in a historical setting and inside a video game.

The (American version of the) novel starts with Ye, a scientist from an academic family, hitting what suddenly becomes the worst possible time to be an academic in China. Ye’s career is taken away by the Cultural Revolution, then her family, then her freedom. Just as her life is about to join that list, there’s an urgent job opening for an astrophysicist at a secret government base with an antenna pointing at the stars.

By that time the Cultural Revolution is over, the physicist has her mind made up on metaphysics as well:

Ye found that the real pain had just begun. Nightmarish memories, like embers coming back to life, burned more and more fiercely, searing her heart. For most people, perhaps time would have gradually healed these wounds. After all, during the Cultural Revolution, many people suffered fates similar to hers, and compared to many of them, Ye was relatively fortunate. But Ye had the mental habits of a scientist, and she refused to forget. Rather, she looked with a rational gaze on the madness and hatred that had harmed her. Ye’s rational consideration of humanity’s evil side began the day she read Silent Spring.

[…]

Is it possible that the relationship between humanity and evil is similar to the relationship between the ocean and an iceberg floating on its surface? Both the ocean and the iceberg are made of the same material. That the iceberg seems separate is only because it is in a different form. In reality, it is but a part of the vast ocean… It was impossible to expect a moral awakening from humankind itself.

The sentence I bolded really stood out to me when I reread that quote. Is refusal to forget really what sets a scientist apart? The same sentiment is echoed later in the book as well:

You must know that a person’s ability to discern the truth is directly proportional to his knowledge.

The story then jumps from the Cultural Revolution to present-day Beijing. A string of Chinese scientists are found dead, and the police approach Wang, a brilliant nanomaterials researcher, for help.

At least, we are told that Wand is a brilliant nanomaterials researcher. None of his actions or thoughts betray an iota of excitement about nanomaterials, or about research, or about much of anything. One gets the impression that Wang got to his position by passing a lot of multiple-choice exams, and that he goes to work every day because the nanotech research center offers good dental insurance

Wang discovers that many scientists are playing an advanced virtual reality game called Three Body. The game puts the player on a planet that suffers from eras of chaotic and unpredictable climate, and the civilizations inhabiting it are decimated as they try in vain to predict the weather.

At this point, Wang’s internal life looks like this:

| Things Wang doesn’t give a shit about | Things Wang gives a shit about |

| · Science, physics, nanotechnology. · His wife and son. · Other people. |

· Photography? |

The Three Body game does sound cool though – it contains adventure, science, politics, philosophy, and Archimedes making fun of Galileo. Even Wang begrudgingly adds it to the “give a shit” column and tries to solve it.

Ye’s story is emotionally riveting, and the Three Body game is inventive and challenging, but both serve as exposition to the main plot of the book which takes place on present-day Earth. Unfortunately, as the book moves on the main plot in question the inventiveness and emotion from the first part dry up faster than the Three Body planet during a heat wave.

The dialogues turn into stilted info-dumps:

“Professor Wang, we want to know if you’ve had any recent contacts with members of the Frontiers of Science,” the young cop said.

“The Frontiers of Science is full of famous scholars,and very influential. Why can’t I have contact with a legal international academic group?”

And the plot chart takes a turn in the wrong direction:

And really, it’s all the scientists’ fault.

There’s a particular way that scientific progress appears from a civilization’s 30,000-foot high point of view. In the Civilization video game, for example, “science” is just another accumulated resource, like gold and oil. You manufacture “science producing” buildings, input a budget, and receive a steady output of blue beaker points that give you access to new technologies and an edge over competing civilizations. If the “science buildings” suddenly stopped producing “science”, you may quit the game in frustration and send a bug report to the developers.

Perhaps fittingly for a novel whose strongest point is the description of a video game, Three Body takes this model and applies it to the actual scientists. What Wang discovers early on is that a lot of science has suddenly stopped replicating. And not just the universal and fundamental link between grip strength and socialist attitudes, but things like measuring the mass of an electron. Faced with a situation where basic experiments in particle physics yield different results every time they are run, the scientific community throws a party and giddily announces the dawn of a new age of discovery.

Just kidding, they despair and commit suicide en masse. Or even worse: start philosophizing cynically about the futility of it all. Instead of considering that they need to revise some basic assumptions and get creative, the characters in Three-Body Problem declare:

“In the face of madness, rationality was powerless.”

For the most part, the bodies of Three-Body don’t like each other, don’t care about anything, and don’t seem up to the challenge. In turn, it made me not like them, not care about them, and not invested in the challenge they’re facing.

Three-Body Problem reads like a scathing critique of Chinese scientists (and intellectuals in general). As someone who spends a lot of time with both scientists and Chinese people, the critique just didn’t ring true at all to me.

As a fun place for clever people to work, science academia falls somewhere between a drug gang, a mental asylum, and a biblical tragedy. The people who pursue this path and succeed in it are A) really good, and B) give a shit. Wang is neither.

As for the biologist, she became a biologist because she actually, you know, is obsessed with biology:

My third and best field assignment out of college required that I travel to a remote location […]

A species of mussels found nowhere else lived in those tidal pools, in a symbiotic relationship with a fish called a gartner, after its discoverer. Several species of marine snails and sea anemones lurked there, too, and a tough little squid I nicknamed Saint Pugnacious, eschewing its scientific name, because the danger music of its white-flashing luminescence made its mantle look like a pope’s hat.

I could easily lose hours there, observing the hidden life of tidal pool, and sometimes I marveled at the fact that I had been given such a gift: not just to lose myself in the present moment so utterly but also to have such solitude, which was all I had ever craved during my studies.

Even then, though, during the drives back, I was grieving the anticipated end of this happiness. Because I knew it had to end eventually. The research grant was only for two years, and who really would care about mussels longer than that…

Inside Area X the biologist shares Ye’s ability to observe the world in keen detail and theorize. But when the details start contradicting the theory, the biologist throws out the theory and keeps observing, rather than jumping to grand conclusions.

Also:

I see now that I could be persuaded. A religious or superstitious person, someone who believed in angels or demons, might see it differently. Almost anyone might see it differently. But I am not those people. I am just the biologist; I don’t require any of this to have a deeper meaning.

I don’t require science fiction to have a deeper meaning. And when it does, I prefer not to be hit over the head with it but rather allowed to divine it for myself.

Geeking out about science makes one a science geek, but not necessarily a scientist. What makes the biologist a much better scientist character than the cast of Three-Body goes a bit deeper than caring about biology.

I recently came across this interesting Tweetstorm about “puzzle-box analysis”. Some consumers of fiction or video games insist that every detail in a work has to fit into the main narrative, like an interconnected chain of gears. These readers get upset if some piece of lore isn’t nailed down to a specific in-world meaning, like Watchmen’s comic-within-a-comic Tales of the Black Freighter.

I think that this ties to the psychological construct of ambiguity tolerance-intolerance: how comfortable you are when the world doesn’t fit neatly into boxes. If you are intolerant of ambiguity, the following two things are true:

- You can become a leading scientist in Three-Body’s China, even though real-life China scores pretty low on avoidance of uncertainty.

- You’re not going to enjoy your trip to Area X.

In the words of the biologist:

I am aware that all of this speculation is incomplete, inexact, inaccurate, useless. If I don’t have real answers, it is because we still don’t know what questions to ask. Our instruments are useless, our methodology broken, our motivations selfish.

And yet, the biologist keep going on the strength of just two things: a burning curiosity, and an ability to unlearn as easily as she learns. Those two are also known as the first and third virtues.

Curiosity and lightness are critical if you find yourself in a strange world that defies your intuition. Like Area X, or the Three-Body world, or Zoo City, or… or our own world, in 2018.

In Sapiens, Yuval Harari claims that the discovery that sparked the scientific revolution was the discovery of ignorance. Science started when we realized that the world is scrutable in principle, but in practice, it’s extremely strange and most of what we think we know is dead wrong.

If you asked me a while ago what I knew about plants, I’d have said that they’re living organisms that grow slowly, have things like roots and leaves, photosynthesize, and reproduce within their own species. But Rafflesia arnoldii is a parasite flower that explodes swiftly into a gigantic size, doesn’t bother with roots, stems, leaves or photosynthesis, can heat itself by 30 degrees, is pollinated by carrion flies, fertilized by a different (and yet unknown) species. It also shares a ton of genes with its host plant, genes that it did not acquire through reproduction.

And if that’s how weird botany gets, just imagine what’s going on with consciousness, dark matter, abiogenesis, or any other mystery on the current frontiers of science. I don’t know how or when these mysteries will be solved, but I would bet that they are solved by scientists who are obsessively curious and not overly attached to what they think they knew, not scientists who are good at multiple-choice exams.

Her qualifications as a scientist aside, the biologist is one of my favorite characters in all of fiction. I suspect that it’s for the same reasons that other readers found her incomprehensible, or boring, or even autistic.

The biologist doesn’t describe herself with adjectives, only actions and ideas. She goes to an abandoned swimming pool to observe frogs for hours, or goes out with her husband’s friends just to observe them from the side. She climbs trees. She likes sex and hates small talk.

What drew me most to the biologist is that she is wholly internally motivated. She has a good idea of what others think of her, she just doesn’t care about it for the most part. She doesn’t try to make the psychologist, surveyor and anthropologist like her. She doesn’t try to make the reader like her, which is why so many don’t.

Her husband asks:

“Ghost bird, do you love me? […] Do you need me?”

I loved him, but I didn’t need him, and I thought that was the way it was supposed to be.

I read Annihilation in 2014, around the time I started going on a lot of OkCupid dates. My biggest frustration on those dates was feeling that I’m unable to discover the real personality of the woman I’m talking with. No matter how I tried to turn the conversation to what’s honest and personal, I would be convinced that the person across from me was replaying rehearsed lines, or signaling allegiance to one group or another, or making sure what she’s saying was “appropriate”.

I remember some utterly surreal conversations from those dates:

Her: You did stand-up? Who are your three favorite comedians?

Me: I don’t really keep a top-three list, I just enjoy great comedy bits wherever I hear them.

Her: No, if you’re a stand-up you have to have a top three.

Me: OK, I guess the three funniest people I’ve seen live are Nikki Glaser, Jerrod Carmichael and Sarah Silverman. How about you?

Her: Dave Chappelle, Louis Black and Louis CK. Wait, that’s not OK, I don’t have a woman on my list.

Me: Why is it not OK? It’s your list of comedians. They just have to be funny, they don’t have to be women.

Her (getting angry): Of course there has to be a woman! How can you say a list of top comedians can not have women on it?

I finally came to the conclusion that a lot of these people just didn’t have a “real personality”, a true independent self, waiting to be comfortable enough to emerge. They don’t just act as if they’re pleasing a crowd of judges on a first date, they actually think like that. All the time. I realized how hard it is to find anyone who’s motivated internally by curiosity, or ambition, or desire, and not externally by about passing exams and getting the approval of others and premium mediocrity.

And then, about a year after I read Annihilation, I clicked on an OkCupid profile of a woman at a microscope. On our first date, she made me climb trees in Central Park. When we go to parties, she sometimes just sits on the side and watches people. I have friends who think that it’s strange; I find it endearing. When we went to see Masada, a striking window into history and a natural wonder, her attention was mostly devoted to a tiny brown rodent that was running around. She spent an hour afterward trying to figure out it if was a hairy-footed gerbil or a golden spiny mouse.

And so, for the second time in my life, I fell in love with the biologist.

Great review! Also, the NYC preschool link was broken as of a few minutes ago — just opens a blank tab for me.

LikeLike

Fixed it, thanks.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Bought Annihilation, it sounds really interesting!

LikeLike

To nitpick: a good scientist doesn’t forget. A good scientist doesn’t throw out a data point because it’s inconvenient or seams wrong. If a data point is wrong then a bad process led to getting it and that association should be remembered to avoid that bad process. If a process is sound then the data point has to be correct and taken into account. Sometimes a “wrong” data point can contribute to important discoveries.

Now, not everybody with a good memory is a scientist but forgetful people (in this metaphorical sense) trying to figure things out are doing something other then science. If your description of the book is accurate, the “scientists” in The Three Body Problem aren’t doing science. If the electron used to have a consistent mass but now it doesn’t, a scientist doesn’t flail about and completely replace their existing paradigm ignoring the former (say, a political pundit or an amateur philosopher might) but rather replaces the paradigm slowly and doesn’t completely get rid of the old one.

Not forgetting doesn’t set scientists apart from others but how they don’t forget might.

LikeLike

Three remarks 1. Chinese problem with science seems trivial. Feynman on Quantum Mechanics: “A philosopher once said ‘It is necessary for the very existence of science that the same conditions always produce the same results’. Well, they do not….What is necessary ‘for the very existence of science’ are not to be determined by pompous preconditions, they are determined by nature herself.” 2, Poets are better with memory than scientists. Poetry is one big quotation. Science tends to distill and compress knowledge forgetting the previous level. 3. Started to read Annihilation.

Jacob edit: I have no idea why this comment shows up as if it’s by me, it’s by a reader.

LikeLike

Now I’m curious as to whether I have had very different luck in dating or if I myself lack a personality….

LikeLike

No matter how much you optimize dating, there’s still a lot of luck involved and I definitely got super lucky.

A smart use of OkCupid can narrow down the dating pool to the best 0.1% of matches and let you meet 50 women a year, but if you’re looking for someone who’s 1 in a million it may still take you two decades :)

LikeLike

This doesn’t seem to have gone through the first time…

1st. My officemate recommended Annihilation but with a second rec I’ll bump it up my list. (after The Will to Battle)

2nd. Not super relevant but a prime example of ecology fiction is the Oryx and Crake trilogy. It’s one of Margaret Atwood’s more sciencey works.

Finally, on the three body problem. I really enjoyed this book. Granted I was kinda angry at it for taking a sharp turn partway through, but it is rare for a book to surprise me so I appreciated that. Anyway I finished the trilogy and enjoyed it. Unfortunately a different guy translated the second book so it has a weirdly different tone and puts names “given family”

I sort of agree with you that Wang’s character is underdeveloped. But I just interpret him as being depressed. But also he is primarily an engineer, which is more about manipulating the science we know.

On “being a scientist means you cannot forget”. This is an important aspect of research. When your experiment doesn’t work and suddenly it does you cannot just accept it you must understand why. You must always understand what part of your experiment is limiting your precision. I believe this is similar to not simply going with the flow when your country has recovered from a horrible experience. You must understand why it happened and why it stopped. Partially to prevent it in the future but also just for knowledge’s sake.

In terms of scientists’ response to the unknown I have several comments, related to both in-universe and out-of-universe differences.

In-universe, from what I understand from your summary, the weird part in Annihilation occurs only in Area X? That means it is not the familiar becoming strange, it is the discovery of the completely unknown. By contrast, in Three Body Problem, Newton’s laws stop working. This is not analogous to e.g. the discovery of quantum mechanics and subsequent causality violations. Because despite all this, experiments that already worked did not stop working.

In-universe again, perhaps biologists are more open to strangeness because it is primarily an observational science. I think physics is more predict-verify. (Btw I am a physicist).

Finally, out-of-universe, I believe it is significant that Vandermeer is primarily a writer, and in particular a New Weird writer. Liu is an engineer. I think Liu’s representation of scientists’ responses is much more realistic. Vandermeer’s is idealistic. We are people too.

LikeLike

I was thinking about this (the scinenstness of the scientists in The Three Body Problem) some more yesterday. For background I merely have an undergraduate degree in physics. This does not make my a physicist so I should differ to your expertise. I also have not read any of these books being discussed.

First, I am curious as to what you refer when talking about the causality violations of quantum physics. I know of two things to which you could be referring: the probabilistic nature of measurement or Bell’s Theorem.

As per the probabilistic behavior, yes some events in quantum physics appear to be completely random governed by a probability distribution which might lead one to conclude that an effect might not have specific causes. I disagree with this as the evolution of the probability distribution (the wave function of a thing) proceeds from specific causes and in a known and usually in a predictable way. If one considers the wave function to be the truly important aspect of a thing then this difficulty, seams to me, disappears. When a wave function is forced to make a probabilistic change, it consistently changes based on the relevant probability function. I have no problem considering the event causing this change to be a cause of the new wave function.

With respect to Bell’s theorem, it is my understanding that one cannot send information in a way that violates causality. If one separates two net spin neutral electrons a distance away and two people make measurements in quick succession, the electrons will somehow arrange themselves to give consistent responses (one will be spin up and the other spin down) even when the measurors are so far apart that a speed of light message cannot connect the two measurements. Since local hidden variables cannot be the solution, this begs explanation and is interesting but the results in this situation doesn’t fundamentally change: either electron still has a 50% chance of being spin up and a 50% chance of being spin down when measured at either location. If one seeks to force a specific state to send a message faster then light (and thus violating causality) then one would break entanglement and the effect disappears. I fail to see a causality violation (note that this could easily be a failure of my vision).

Now my understanding of quantum physics is enhanced by it being around for a century. Some of my explanations may have taken time to develop and it might have seemed like the new science caused problems for causality at some time. Further exploration both refined the notion of causality and demonstrated consistency with it. If any of my understanding is wrong, please correct me.

Back to the book. There is still a lot about things that aren’t understood. The expansion of the universe due to dark energy could be caused by something internal to the universe or by something outside of it. Until a mechanism is identified, the expansion could abruptly change without any possibility of warning or understanding as to why. The explanation in which this cannot happen are simpler and thus to be favored but if the universe is being externally “heated” in a way that causes quicker and quicker expansion is still a realistic possibility. If the heating stops, for whatever reason, then dark energy may completely disappear.

It’s harder for me to imagine but some unknown thing may be keeping physics consistent or something external to the universe may cause fundamental changes to this consistency. If constancy changes, then something significant has changed and this is exciting to me. This is something that begs explanation and enthusiastic exploration. That said, I haven’t devoted my life to a scientific paradigm. I can understand if those who have might not react well if that paradigm is suddenly destroyed.

Also, in a country with thousands of physicists, if a fundamental change to reality causes a small percentage of them to become suicidal, then there will still be several suicidal physicists. The complaint that there aren’t more dead scientists in this universe seams as valid to me as there being too many. The Earth, to my knowledge, not having gone through something like this, I cannot say what will happen.

It’s also important to note that in my understanding and statistically speaking, the school system in the PRC produces graduates with comparatively better technical skills and knowledge and comparatively worse creativity then the school system in the USA (note that not every Chinese person has been educated in the PRC). It is not unrealistic that, statistically speaking, PRC educated scientists could have a hard time dealing with such a drastic change to reality.

It also occurred to me that if there is something that causes previously reliable experiments to become unreliable it is easily possible that this thing negatively effects the health (including mental health) of scientists leading to increased mortality. If Cthulhu is all of the suddenly imprisoned on Earth then this could cause all sorts of strange effects but would also prevent human scientists from directly investigating the phenomenon.

LikeLike

Hah I’m hardly an expert. Just got my BS two years ago and have working in a federal lab.

I was thinking of Bell experiments. Just because you cannot send information using entanglement collapse does not mean it is not non-local. I’m being sloppy with locality vs causality because the causality problems are because of the speed of light.

And related to what another commenter said about paradigms shifting slowly: when Einstein Podolsky and Rosen predicted “spooky action at a distance” they concluded that quantum mechanics must be incomplete, not that reality is non-local.

LikeLike

I think we may largely be in agreement. The non-locality of Bell’s Theorem is extremely interesting. I can understand how someone (like Einstein) can conclude that this violates causality but I think it merely refines the notion of causality.

I feel compelled to point out that Einstein was against randomness having any place in physics for philosophical reasons and reached for anything to justify his assumptions. Ultimately science has proved him wrong on this. This story exemplifies the humanity of individual scientists and the inhumanity of science as a whole. Reality just doesn’t care about human opinions and will do what it will do even if that means that true randomness exists or that reality is non-local. Science eventually has to come to terms with things that violate one human philosophy or another.

Now in a sense, quantum mechanics and relativity changed the prevailing paradigms in physics rather quickly but, my point in calling the shift slow, was that it didn’t change anything all at once. It also has taken a while for individual scientists to catch up to what the new science was telling them about reality. The shift from reality being locally based to non-local reality is still going on in society at large even if physicists are comfortable with it (and indeed have the non-local quantum field theory).

There are also things discovered preciously that stick around like conservation of momentum or the arrow of time from the earlier paradigm into today’s. Also, as a practical matter, the previous paradigm is used exclusively when solving some real world problems. Quantum mechanics is directly necessary for semi-conductor design but not for designing a new office building.

LikeLike

I apologize for responding to my own comment but I feel like I need to state some corrections. The first correction is that I should not have claimed that quantum field theory is non local. I don’t understand the theory well enough to make this claim and in my reading this week, I gather that most field theories are local or at-least aren’t definitively non-local. I got excited and made an unsupported claim in the heat of the moment.

I am less embarrassed about the second correction. I haven’t looked at Bell’s theorem in a while and I forgot some of the nuance. Bell’s theorem (in simple language) states that objects cannot have every single property determined by local factors at the same time. Bell’s theorem has been rigorously tested and is almost universally considered true by physicists.

The most popular explanation for Bell’s theorem is that reality is non local. A property of one thing can depend on the property of another thing some non-zero distance away. This doesn’t violate the basic assumption of causality (that an event at present or in the future cannot be caused by an event in the past and it’s corollary that an event cannot be a cause of an event that is at a distance in time and space that light in a vacuum cannot travel from the cause to the effect) as one cannot deliberately affect a distant event’s outcome even if there is some type of connection. There are various conjectures of how reality could be non-local.

The less popular but still not exactly unpopular explanation is that things don’t have all of their properties defined at the same time (this is stated as reality being non-real). The Heisenberg uncertainty principle says that one cannot know the exact position and the exact momentum of a thing at the same moment in time. This is because either one cannot know both at once or because both things don’t exist at the same time (in this latter case, something can possess both position and momentum at the same time but neither has just a single value that it is). The standard Copenhagen interpretation of quantum mechanics favors the former case but that latter case would explain Bell’s theorem. If one considers something’s wave function to be what it fundamentally is (something that is not the most popular explanation amongst physicists) then this would be an answer to Bell’s theorem.

There are outright unpopular explanations such as reality being completely determined: that is the true probability of any event happening ever in the past present or future is either 0% or 100% (and thus if something appears to have a different probability, it’s only because of some type of ignorance).

Note that these explanations are not necessarily incomparable with each other. Reality could be non-local, non-real (that an object could fundamentally fail to have an exact momentum at all times for example), and completely deterministic. Bell’s theorem (largely) basically says that at-least one of these things has to be true.

As always, I’m not an expert on… well anything. You should always keep this in mind when you pay attention to me. I do find the implications to Bell’s theorem (and, in a sense believe all three explanations) exciting and love discussion about it even if nobody is exactly an expert in the particular discussion.

LikeLike

This is false. In the book, everyone’s cars still work, their radio transmitters are just fine, they can still open doors and play baseball and walk and talk exactly as before. It’s only in a very few very particular settings (experiments around physicists susceptible to depression) that things go weird. Just like the quantum mechanics case (experiments around particular very small-scale phenomena).

A real scientist would immediately jump on those distinctions and try to figure out exactly what changed, when, and what the new rules are. I won’t spoil the answer here, but I would not be surprised if the settings, along with the fact that the irregularities began after a certain point in time, make the correct explanation, if not proven, at least prominent and plausible. But for some reason none of the “scientists” in the book care to explore this at all.

PS: Was anyone else bothered by Three Body Problem’s misunderstanding of days vs years? The earth’s revolution around the sun causes the annual cycle; the day-night cycle is caused by the earth’s rotation around its axis.

LikeLike

Not sure if this is the right place to ask, but couldn’t find it anywhere! Does this blog have an RSS feed? I’m a huge fan, and would love to be able to add it to the way I read the rest of my blogs!

LikeLike

cc, thanks for alerting me. I’ve added a widget with RSS links to the right side menu, or you can just access them via putanumonit.com/feed/ and putanumonit.com/comments/feed/

LikeLike

When I saw that you were comparing two books, but only found one satisfying I made this guess: “Well Annihilation is topically relevant because the movie is coming out, so this would be a good opportunity to contrast it with some other book that he likes.”

I just want to give you a point for subverting my expectations!

LikeLike

typo: Wang misidentified as “Wand” once.

LikeLike