9/5/19: This post has been translated to Russian by Vladimir. Thanks!

Bad news: The replication crisis in psychology replicated. Out of 21 randomly chosen psychology papers published in the prestigious Nature and Science journals in 2010-2015, only 13 survived a high-powered replication.

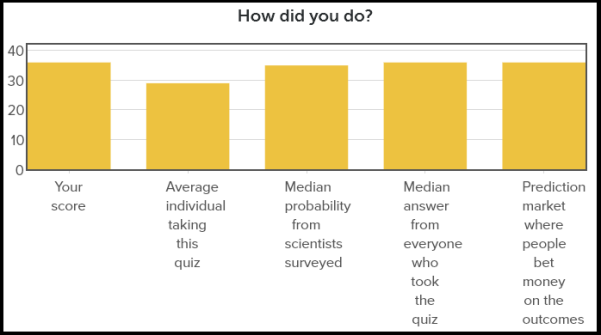

Good news: A prediction market where research peers could bet on which results would replicate identified almost of them correctly. So did a simple survey of peers with no monetary incentive.

Better news: So could I.

Best news: So can you.

Rob Wiblin of 80,000 Hours put together a quiz that offers descriptions of the 21 studies and lets you guess if their main finding replicated or not. I recommend trying this out for yourself. If you’re not confident in your sniffing ability you can review some of my previous posts on defense against the dark arts (of bullshit statistics).

The stench of bad research is difficult to hide, and a few simple rules are enough to tell the true insights into human nature from the p-hacked travesties of science. Here’s what you need to know to ace the quiz and avoid falling for the next piece of psych nonsense.

Rule 1: The Rule of Anti-Significance.

If a study has p=0.049 it is fake.

There are two studies in the quiz with p-values just below the common 0.05 threshold. I immediately (and correctly) identified both as fake without reading anything else.

If you take a Statistics 101 class at most universities, you are taught the following rule of statistical significance:

A result with a p-value above 0.05 is probably false. A p-value below 0.05 is statistically significant, meaning the result is true.

It’s never phrased like that explicitly, but that is the implied rule that people learn as they “test” hypotheses against the 0.05 threshold to get an A in the class. I got an A+ in my statistics class in grad school by following this rule religiously.

But that was a long time ago. Today, allow me to present Jacob’s Rule of Anti-Significance:

A result with a p-value just above 0.05 could well be true. A result with a p-value just below 0.05 is almost certainly false.

If you understand why this is so, you know all you need to about statistics in research.

Let’s start with the first part: how likely is a result with p=0.06 to replicate?

p=0.06 roughly means that the measured effect is 1.5-1.9 times the standard error, depending on the test used. The measured effect is some combination of true effect and noise. Even if noise accounts for half the measurement, the true effect is something like 0.8 times the standard error in the experiment.

But the standard error is a function of sample size – it should decrease with the square root of the number of subjects. When we run a replication with 10 times the sample size (which many studies in the replication project did), the standard error will be roughly 3.1 times lower. This means that the true effect is now 0.8*3.1 = 2.5 times the standard error of the new experiment with the larger sample. This is more than enough for a successful replication. Some p=0.06 result will be entirely due to noise, but a lot of them will point to something real that just needs to be confirmed by a stronger replication.

More importantly, p=0.06 means that the researchers are honest. They could have easily p-hacked the results below 0.05 but chose not to. The opposite is true when p=0.049.

The chance that the p-value of a study will land precisely in the 0.045-0.05 range is 0.005 (1/200) if the effect doesn’t exist. Even if the effect is true and equal precisely to the p=0.05 line, there’s a mere 1/60 chance of the measured p-value falling in that tiny window.

But if a study was p-hacked, if the researchers kept juggling different hypotheses, including and excluding outliers, and tweaking the measurements, then it is almost guaranteed to land in the 0.045-0.05 range because that’s where the hacking will stop and the champagne will pop.

In Bayesian terms, which are the terms we should be using anyway, a p-value in the 0.045-0.05 range gives a 60-200 times higher likelihood to the hypothesis “the study was p-hacked by bad researchers” than to the hypothesis “the study landed on that p-value by accident”. And since unscrupulous (or just clueless) researchers in psychology are certainly more common than 1 in 60, the conclusion (i.e., posterior) is that a study with p=0.049 got that p-value by bullshit means, and its result is bullshit.

2: The Rule of Taleb’s Grandma

If the purported effect sounds implausible, it is.

You have a mind capable of simulating itself, which lets you replicate any psychological study inside your own head with N=1.

Example 1: “People prefer watching TV for 12 minutes to being alone with their thoughts for 12 minutes.” Right now, you’re reading this blog because you don’t want to be alone with your thoughts. This experiment replicated easily.

Example 2: “If you imagine eating an M&M 30 times, immediately afterward you will eat fewer M&Ms from a bowl.” Do it. Imagine yourself eating an M&M: picking it up, chewing, swallowing. Now do it 29 more times. You can almost certainly feel your attitude towards M&Ms changing.

I don’t know if I would have guessed ahead of time that the effect would be to make me want fewer M&Ms, but it’s certainly plausible from my N=1 thought experiment that there would be a detectable effect one way or another. Of course, if the effect was to make people eat more M&Ms, the study would still be published! Whichever way the effect goes, I had reason to believe it would be true. This study also replicated, with good effect size.

Example 3: “Washing your hands makes you less likely to want to justify your decision of how you ranked music albums, but just thinking about soap doesn’t.” Imagine yourself washing your hands. Do you feel any impact whatsoever on your desire to rationalize decisions? Now imagine explaining this study to Nassim Taleb’s grandma.

Psychologist: You see, Taleb’s grandma, there’s a clear link between washing your hands and justifying album-ranking choices.

Taleb’s Grandma: What the fuck are you talking about?

Psycho: Cleaning one’s hands “eliminates the postdecisional dissonance effect” by priming you to think of a “clean slate”. Those are scientific terms, so you know that this is serious science.

Grandma: Just because we use the word “clean” in English to refer both to hands and to your conscience doesn’t mean that thinking about cleanliness in one context will change your behavior in the other context. That’s cockamamie.

Psycho: No, no, just thinking about washing your hands is not enough to prime you, even though every other priming study says it’s enough to just think of things. Thinking about soap doesn’t do anything. You need to actually wash your hands to get the effect, and not just because we tried different ways of priming and only reported the one that gave us a publishable p-value.

Grandma: Ok, so you’re saying that washing my hands makes me want to “come clean” and explain my decision on how I ranked some albums?

Psycho: It’s the opposite! Washing your hands makes you less likely to explain your decision because you already think of yourself as metaphorically clean.

Grandma: This story about washing hands and explaining decisions depends on a conjunction of multiple steps, every one of them individually preposterous, and with the effect direction at each step chosen completely at random. There are more burdensome details in this hypothesis than can be lifted by 40 exhaustive studies with hundreds of participants each, let alone a single study with 40 undergrads who don’t lift. This is ridiculous bullshit, and I need to wash my ears with soap just to remove all trace of this nonsense from my brain.

Psycho: Well, it was good enough to get published in Science. Are you saying that peer review by experts isn’t a guarantee of true results?

Grandma: Wait till I tell my grandson about this, he’ll make an entire career out of mocking people like you. #IYI #SkinInTheGame #LindyEffect

We can summarize the takeaway in an addendum to rule 2.

Rule 2b: we should all be embarrassed that we believed in priming even for a second.

Rule 3: The Rule of Multiplicity

If the study looks like it tried 20 different things to get a p-value, it has. Whatever effect it claims to have found is just an artifact of multiple hypothesis testing.

I wrote a couple thousand words already about why a study that tries several hypotheses and doesn’t correct for multiplicity isn’t worth the pixels it is written on. That’s my least-read-adjusting-for-quality post ever because even readers who click on a self-proclaimed “math blog” called “Put a number on it” don’t want too much actual math in their blog posts.

The fun part is that you can guess which studies are multiplicitous just from their abstracts. Here’s how one of the studies was summarized on the 80,000 hours quiz:

When holding and writing on a heavier clipboard, people assessing job applicants rate them as ‘better overall’, and ‘more seriously interested in the position’.

The non-metaphorically heavy clipboard already carries the stench of priming, and as soon as I saw the word “and” in the description, I knew it was fake without looking at the sample size or p-value. I could just imagine the researchers trying 27 clipboards of different materials, 4 surveys plus 15 blood tests to measure impact, and 906 interaction effects just to be sure that something somewhere will hit a publishable p-value.

Here’s are some excerpts from the actual paper (courtesy of our heroes at Sci-Hub):

Physical touch experiences may create an ontological scaffold for the development of intrapersonal and interpersonal conceptual and metaphorical knowledge.

The first sign that you’re about to be fed bullshit is an abstract full of 4-syllable words where 2-syllable words would do.

The experience of weight, exemplified by heaviness and lightness, is metaphorically associated with concepts of seriousness and importance. This is exemplified in the idioms “thinking about weighty matters” and “gravity of the situation.”

Priming is really like the Kaballah, where semi-arbitrary coincidences of language have the power to shape worlds.

In our first study, testing influences of weight on impression formation, we had 54 passersby evaluate a job candidate by reviewing resumes on either light (340.2 g) or heavy (2041.2 g) clipboards. Participants using heavy clipboards rated the candidate as better overall and specifically as displaying more serious interest in the position.

However, the candidate was not rated as more likely to “get along” with co-workers, suggesting that the weight cue affected impressions of the candidate’s performance and seriousness, consistent with a “heavy” metaphor, but not the metaphorically irrelevant trait of social likeability.

Does anyone actually believe that if the candidate was rated as easier to get along with they would admit that it contradicts their hypothesis instead of making up a just-so story about how the candidate is a “solid person” you can “lean on”?

Our second study investigated how metaphorical associations with weight affect decisionmaking […] Here, a main effect of clipboard condition, was qualified by

an interaction with participant gender.

When you’re desperate for p-values and need to come with 100 new hypotheses to test, breaking your group into arbitrary categories (by gender, age, race, astrological sign…) is the easiest way to do so. This is the “elderly Hispanic woman effect”.

Comparable to study five, participants who sat in hard chairs judged the employee to be both more stable, (p = 0.030), and less emotional, (p = 0.028), but not more positive overall . On the negotiation task, no differences in offer prices emerged (p > 0.14).

We next calculated the change in offer prices from first to second offer, on the presumption that activating the concepts of stability and rigidity should reduce people’s decision malleability or willingness to change their offers.

Among participants who made a second offer, hard chairs indeed produced less change in offer price (M = $896.5, SD = $529.6) than did soft chairs (M = $1243.6, SD = $775.9).

This study is basically a p-hacking manual. They’re not even trying to hide it but describe in detail how, when a hypothesis failed to yield a p-value below 0.05, they tried more and more things until something publishable popped out by chance.

It’s OK if one study finds that clipboard weight only affects measures A and B and not C, and only does so for women and not men, if you then run another study that only looks at A, B, and women. But a study that tried 100 things and tells you about 3 of them is like a criminal on trial who mentions that there are some banks that he didn’t rob.

4: The Rule of Silicone Boobs

If it’s sexy, it’s probably fake.

“Sexy” means “likely to get published in the New York Times and/or get the researcher on a TEDx stage”. Actual sexiness research is not “sexy” because it keeps running into inconvenient results like that rich and high-status men in their forties and skinny women in their early twenties tend to find each other very sexy. The only way to make a result like that “sexy” is to blame it on the patriarchy, and most psychologists aren’t that far gone (yet).

So: “Participants automatically project agents’ beliefs and store them in a way similar to that of their own representation about the environment (a comparison of the mean reaction time between the P-A- treatment and the P-A+ treatment)”. I fell asleep just copy-pasting that abstract. This terribly unsexy study replicated with a large effect size.

“Participants in a condition that simulated the stress of being poor did worse on an attention task than those who simulated the ease of being rich.” Muy sexy, as is anything that has to do with educational interventions, wealth inequality being bad, discrimination being really bad, or any other result that easily projects to a progressive policy platform. Of course, the replication found an almost-significant result in the opposite direction of the original — people in the “poor condition” paid more attention and did better.

Anything counterintuitive is also sexy, and thus (according to Rule 2) less likely to be true. So is anything novel that isn’t based on solid existing research. After all, the Times is the newspaper business, not in the truthspaper one.

Finding robust results is very hard, but getting sexy results published is very easy. Thus, sexy results generally lack robustness. I personally find a certain robustness quite sexy, but that attitude seems to have gone out of fashion since the Rennaisance.

Reasons for Optimism

Andrew Gelman wrote in 2016:

Let’s just put a bright line down right now. 2016 is year 1. Everything published before 2016 is provisional. Don’t take publication as meaning much of anything, and just cos a paper’s been cited approvingly, that’s not enough either. You have to read each paper on its own. Anything published in 2015 or earlier is part of the “too big to fail” era, it’s potentially a junk bond supported by toxic loans and you shouldn’t rely on it.

While it’s certainly true that a lot of psychology was junk science in the pre-2016 era, it wasn’t clear whether things will improve from 2016 onwards.

The replication crisis in psychology is not a new phenomenon. Statistician Jacob Cohen noted that most studies in psychology are underpowered and full of false positives back in 1962. In 1990, he noted that things have only gotten worse. Why were voices like Cohen’s ignored for more than 5 decades?

My hypothesis is that:

- Most psychologists couldn’t understand the mathematics of what was wrong or didn’t care to try. The standards of the field were such that they could get away with criminal methodology.

- The psychologists who did care about mathematical rigor were at a disadvantage since they couldn’t match the publication output of their p-hacking counterparts. A lot of them probably left to do something else, like advertising in the 1960s or consumer data science in the 2010s.

But it’s harder to get away with bullshit studies if everybody knows how to spot them and everybody knows that everybody knows. If you and I can guess which studies will replicate with close to 90% accuracy, the editors of Nature and Science also can, and now they’ll have to instead of batting 62% (13/21). Researchers can’t pretend that the “replication messed up the experiment” if everyone can tell at a glance that the study will never replicate.

There are ways to improve the reliability of psychology research that require learning some math, although not beyond what one can learn from reading Putanumonit: estimating experimental power, calculating the likelihood of alternatives instead of null-hypothesis testing, correcting for multiplicity. But there are also fixes that don’t require knowing any math at all, like preregistering the analysis, being suspicious of interaction effects that were not in the main hypothesis, and getting a larger sample size than 20 undergrads who do it for course credit.

Hopefully, psychology researchers have started doing these things in the few years since it became clear that bullshit will be caught. And if they haven’t, we’ll catch them.

This is unfair – you’re judging the ones that were already accepted, while they were judging submissions. For all you know, they scored 90% on the ones that were submitted and the vast majority of submitted ones are noise

LikeLike

That’s a good point. Is there a good source of psychology preprints, sort of like arxiv?

LikeLike

https://psyarxiv.com should be what you’re looking for

LikeLiked by 1 person

is it really a good point though? seems like they could just re-evaluate the papers by giving them a second look (by different editors in the same journal)

LikeLike

My score was 24. Hmm, I wonder if I’d have done better if there were no “I don’t know” option… should’ve kept track.

LikeLike

That can tell something on the present battle order in psychology (I must say that I admire young data thugs): https://www.chronicle.com/article/I-Want-to-Burn-Things-to/244488?key=ONA-J8qTe05O7njbTd0tJxVPc8Wh8rPZLgfV3j9qtQvPw_NSaQoPLX5LOtOxfok8TDJSbDZYakViRTN1RW9qdjFKT1BZUUJTc3dBUjM0N1AyRlFJV2dnVzEyQQ

LikeLike

I just saw a link to that article today. I wonder if those defending the old order realize how pathetic they sound.

I can’t wait for this person and everyone like them to finally leave psychology for their true calling: astrology and Tarot cards. I get emails from grad students who left psychology because they couldn’t compete with the bullshit factory, and their professors got angry when they started talking about statistics and methodology.

Oh, no! How can anyone do science when they have to actually withstand scrutiny? So unfair! It used to be that you could just write NY Times clickbait and get a book deal, now you actually have to, gasp, discover things. Do they really think that the wheel will turn back? Right now all they’re doing is standing in the way of the house cleaning that will allow the next generation of researchers to do some actual science.

LikeLike

I just had a conversation with my friends on a vacation where they asked me why I left grad-school in Psych: your comments are almost verbatim what I told them. I can recall the time I told a professor that myself and some other peers thought the methods for “scrubbing” some of the study’s databases looked unethical and did not actually present the facts. I received scornful looks and told that it is common practice – I couldn’t believe that was considered common. I promptly left that year.

LikeLike

Is there any merit to psychological constructionism? If you’re not familiar, it’s a research program that turns away from a lot of how psychology was regularly done e.g., facultative parts of brain and mind and neurophysiological correlates that are touted as the locations of emotions or thoughts.

I can’t evaluate the rigor of the studies themselves, but the counterintuitive ideas have been very useful. One of them being this move away from focusing on homogeneous constructs of emotions and instead bothering to consider the heterogeneity as not just statistical error but part of a population of instances. For example, the more common drive in research to find similar instances of ‘fear’ which exclude any dissimilar instances as outside the boundaries of the fear construct. In contrast, their research program still considers these dissimilarities worth exploring. They aren’t beholden to finding probabilistic patterns of relations between every instance of an emotion category.

“Psychological construction theories make no claims about specific patterns for each emotion category, so their validity does not rise or fall based on finding them. Psychological construction theories provide an alternative explanation to basic emotion and appraisal theories in the event that such patterns are found (which would have to be ruled out for those theories to be correct), but psychological construction also can explain why such patterns rarely, if ever, materialize.” From The Psychological Construction of Emotions, 2015.

They try to explain emotional phenomena by treating them as higher-order constructs rather than elemental building blocks, and in doing so, try to find more elemental and granular components that can reliably predict the variability in heterogeneous instances of the ‘same’ construct rather than shoehorning more p <0.05 research that just adds sediment to a generally agreed definition of the construct while sweeping anything that doesn’t agree under the rug as another “more study is recommended to explain these results.”

Any holes in this argument? My foundations in statistics are hazy at best but it feels like a step in the right direction.

LikeLike

From the abstracts I read, it seems like a legitimate approach to ‘wandering around’ in hypothesis space, but I don’t see how it’s a replacement for rigorous statistics. Eventually, if you want to say something meaningful about humans in general rather than just about test subject #42, you have to bunch them into groups that you consider homogeneous for what you need up to noise, and show significant differences. Looking at human and cultural variety to come up with unorthodox classifications is a neat idea, but you still need to prove the results.

It seems equivalent to me looking at something weird in an image from the microscope and telling my advisor “it looks like an experimental artifact, but I don’t know what could cause it, and maybe it’s insert weird chemical explanation”. It’s a great starting point for new research, but I won’t put it in a paper unless I properly followed up on it.

LikeLike

This falls under two of your categories: 1. 4 syllable words instead of 2 syllable words (which you say is evidence of bad bullshit); 2. unsexiness (which you say is evidence of good study).

LikeLike

OMG, thank you for outlining all this so clearly! I’m actually a psychologist, had to study all those stats. I learned about Bonferroni corrections in UNDERGRAD! But that was in Brazil … when I got to grad school in North America, there was all this ‘cleaning up’ of data sets going on ….

So I gave up on research and became a clinician and a teacher. Then I discovered research in education! 34 participants, 14 statistical tests run, and NOBODY has even heard of correcting for that. And everybody takes the research so to heart, with nothing changing even after it’s shown to be complete bullshit (learning styles, anyone?). It’s WORSE than research in Psych, which is very very depressing, considering the role of our education systems in all our lives …

Don’t even get me started on analysis of variance …. Since WHEN did fancy fiddling with correlations allow us to say anything at all about causation.

Sigh.

I love that replications are happening, finally. I’ve been suggesting for decades that every Master’s degree in any Psych field should be a replication, preferably a high-powered one. Ditto education.

When they make me king, a lot of things are going to change around here ….

LikeLiked by 1 person