Alternative title: The finance industry, mortgage-backed securities, bank bailouts, risk-weighted assets, and equity ratios: much more than you wanted to know.

Also: you get to find out what I actually do for a living.

Epistemic status: I look forward to learning a lot from the comments.

Follow up post: how finance improves and turkeys in the jungle.

Galaxy Brain

13 billion years ago the first galaxies started forming, followed soon after by the galaxy brain meme. Sometime in between, Scott Alexander wrote about the root of galaxy-brainism: the irresistible urge to signal intelligence by adopting meta-contrarian positions. This urge is so strong that it is nearly impossible to find an issue where people up-and-down different levels of education and left-and-right on the political spectrum agree with each other. Nearly impossible.

Dropout or Ph.D., Trumper or Berniebro, everyone seems to hate the financial industry. People signal intelligence or political affiliation not by having different attitudes towards finance, but by using different buzzwords to explain why bankers are evil and should be fired/jailed/eaten.

To the consternation of all the brains pictured above, the only people who seem to respect finance are those with any real power. Tech companies have enough cash not to worry what bankers think of them, and yet it’s quite rare to hear a tech CEO criticize Wall Street. Voters on both sides of the spectrum hate bank bailouts, and yet presidents from both parties keep bailing banks out. Even Trump, who has appointed criminals and scammers to every post in the cabinet, was convinced to pick a moderate and well regarded professional to chair the Federal Reserve.

“They’re all in the bankers’ pockets” lacks explanatory power. Rich and powerful people spend most of their energy fighting other rich and powerful people, not altruistically conspiring with them. And the finance industry isn’t even that rich. Johnson & Johnson is bigger than any bank in the world, why aren’t the rich and powerful in the pocket of Big Band-Aid?

I have an alternative explanation: Finance is the miracle glue that keeps our civilization intact. No one understands exactly how it works, so fucking with it in any way should be terrifying. People in power can see that.

I see scowling faces when I propose this explanation, or when I suggest that finance is important and bankers are doing useful work. The confidence with which people proclaim that finance is parasitic and worthless is in direct proportion to their ignorance of any theory or facts pertaining to the financial industry.

There’s a lot I don’t know about finance. I don’t know which complex criticism of finance are correct, but I know which simple ones aren’t. I will list some basic facts, do some basic math, and present a basic model of what finance does. Any criticism of the finance industry should at least address these basics. A lot of them don’t, and that includes books written by economists, not just Twitter trolls.

The goal of this post is to push you up the Dunning-Kruger curve towards less ignorance about the finance, less reflexive hatred of it, less confidence that you know how to “fix” it.

Welcome to the galaxy brain.

The Parable of Banksy

Imagine a world made up of two villages, a week’s ride apart. Maysville, where corn is grown and eaten, and Cottonton, which produces cotton. The resident of both villages work diligently, but their lives aren’t great. The Maysians eat well but have nothing to wear but tunics stitched of corn leaves; the Cottonites have good fabric but meager lunches.

There’s one Maysvillian, Banksy, who just sucks at growing corn. At harvest, he barely has enough cobs to fill a single cart. But then Banksy has an idea. He takes the cart and rides out of Maysville, returning after a fortnight with a cart full of t-shirts, jeans, and underwear. The Maysians are happy to trade huge amounts of the corn they don’t need for a pair of MeUndies. After a few trips, Banksy has as much corn as the best farmers in town.

Some of the older farmers sneer at the young entrepreneur. “In my day, to get a silo full of grain you had to pull it out of the ground yourself”, they mutter. “What did you do to deserve your riches?”

“I took on price risk and foreign exchange risk in connecting our village to geographically diverse markets”, replies Banksy.

“Sounds like a scam”, say the elders.

A while later, two women named Tori and Tilly are walking around Maysville telling everyone about a new idea they came up with. Instead of eating the corn raw, they could dry and mill it into flour, then bake it in flat circles. They named it after themselves: a tortilla. Unfortunately, the tortillas so far are hypothetical: Tori and Tilly don’t have enough corn to pay builders to construct a corn mill, and no one in Maysville is willing to work for free.

Banksy comes with a proposition: he will lend the two women 10 bushels to pay the laborers, and they pay him back 20 bushels when their tortillery is set up. Tori and Tilly agree, and soon Maysville is booming with baked delicacies of every sort from nachos to cornbread. Unfortunately, Tori and Tilly go out of business after an angry mob accuses them of cultural appropriation.

Banksy is richer than ever, and the elders are angrier than ever. “You used to pull your cart, now you get rich just by sitting around!” they shout.

“I took on time risk and credit risk by allowing our village to trade not just across geographies, but also across time,” says Banksy. “We are 99%!” the elders keep screaming as they slowly shrink and transform into corn cobs.

This is ultimately what finance does. It’s the intermediary that allows people to trade across time and space, and the party that assumes many of the risks inherent in this trade.

Finance is a Coordinating Intermediary

You may notice that it takes 1 intermediary to connect 2 villages, but 100 nodes have 4950 potential connections. A billion people have half a quintillion potential connections. The more actors participate in the global economy, the more middlemen it takes to connect them. The value of making those connections increases as well, as does the risk. As the global economy becomes more integrated we should see three things happening, and they do:

- Finance, insurance and trading take up a larger share of the global economy.

- Finance becomes riskier, more lucrative, and more unequal with greater rewards going to the winners. [1]

- Everyone in the world gets more prosperous.

This is what financial institutions do and how they make money. Goldman Sachs doesn’t rob people at gunpoint, it gets paid by willing clients to provide a service. Finance create value by connecting people: companies to investors, depositors to lenders, corn buyers today to corn sellers next year. You can argue that risks are not worth the rewards or that inequality is not worth the prosperity, but that doesn’t erase the value that finance provides.

Take the most vilified financial innovation of the past few decades – the mortgage-backed security. It’s built on a simple idea: instead of making an all-or-nothing bet that a single family will pay off their house by issuing a single mortgage, a bank can package 10,000 mortgages together into an MBS and you buy a piece of that, equivalent to making a bet that at least X% of the mortgages will get paid.

This is a really good bet when X is 10% or 40% or even 80%. But if X is 95% and all you own are crappy MBS, it takes just 5% of American borrowers defaulting on their mortgages at once to blow your shit up. This is what happened to Lehman Brothers and AIG, and it’s how we got a financial crisis.

It’s very tempting to draw the lesson from this that MBS are useless and risky, or that they’re a scam invented by greedy bankers to steal money.

But we can look at MBS as a solution to a coordination problem. There are 10,000 families who want to move into a house today and pay for it over a couple of decades. There are 10,000 construction workers who want to build a house today and get paid for it today. There are 10,000 investors who want to invest some money today and get a return in the future.

Those 30,000 people don’t live in the same city, the same country, or even in the same decade. Even if we could magically teleport them to the same (very large) room, they would not be able to coordinate a solution. How would they trust each other to do their part? Who would track how much money needs to get paid to whom and at what time?

Mortgage-backed securities are the solution to this seemingly impossible coordination problem. Without MBS fewer people would live in the houses they want, fewer construction workers will have a job, and investors will get worse returns on their hard-earned savings. The banks who securitize mortgages are in competition with each other and as a result, they capture only a small part of the surplus MBS create for all involved.

Any deal like this carries inherent risk since any subset of the 30,000 can mess things up for everyone else. Investors may pull their money, construction companies may build the wrong houses in the wrong geographies, tenants may default on their mortgages. This risk is unavoidable, and it’s very hard to figure out exactly how much risk was involved, and where it was concentrated. In 2008, the answers turned out to be: “way more risk than we thought” and “concentrated in a few huge and interconnected institutions that may need a bailout to survive”.

If the story so far has been relatively uncontroversial, the opposite is true when we get to the B-word. Fasten your seatbelts.

What’s in a Bailout

The sanity of conversations about the bailout got off to bad start right away. As the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act was debated in Congress, Americans supported the bill by a 27% margin when it was presented as “the government is potentially investing billions to try and keep financial institutions and markets secure” and opposed the same exact bill by a 24% margin when it was phrased as “the government should use taxpayers’ dollars to rescue ailing private financial firms whose collapse could have adverse effects on the economy and market”. Very few of the people expressing their opinion bothered to read the 451 pages of the law, and the same is true of many of the congresspeople who voted on it.

Where do I stand? I stand with Socrates. The financial system is so complex and anti-inductive that predicting the effects of major interventions in it is beyond mortal comprehension. The political system is so complex and anti-inductive that predicting the effects of major interventions it enacts is beyond mortal comprehension. Bailouts are a major intervention in the financial system enacted by the political system. Predicting the effects… Ah hell, let’s at least try.

The argument in favor of financial bailouts is that the financial system relies on confidence, and confidence is a resource that can be cheaply manufactured by the government.

Banks are vulnerable to negative feedback loops where temporary setbacks cause permanent damage. If a few depositors lose faith in a bank and withdraw their deposits at once, the bank has less money available to pay other depositors, which in turn causes them to lose faith and withdraw their funds, and so on until the bank collapses in a bank run. The government can easily put a break on this process by promising depositors that they will always get their money back. Once depositors are sure they can withdraw their deposits, they don’t feel the need to.

A similar thing happens in a liquidity crisis, such as the one in 2008. When banks lose access to loans they can’t finance their own lending in turn, and the market for credit can collapse in a runaway process. Again, the government can provide credibility and prevent the death spiral by being the lender of last resort. Confidence is created by credibility, and as long as the government is stable, solvent, and able to print money, it has the credibility to inject confidence into a panicky financial system without much cost to itself.

There are two main arguments against government bailouts of banks.

The first is moral hazard: if banks are protected from the downsides of making bad investments by an implicit government guarantee, they will make dumber and riskier investments. Had banks known they wouldn’t be bailed out in 2008 they wouldn’t have kept stuffing their balance sheets with explosive subprime MBS. But they knew, so they did.

I think that the general version of this argument is certainly true. But the particular case of subprime mortgages that’s so often cited as an example of moral hazard probably has little to do with it.

The crash of subprime MBS seems obvious in hindsight, but at the time the number of people making bets against these instruments was very small. The most famous of those, Michael Burry, couldn’t even convince his own investors that MBS are too risky and had to enforce a moratorium on withdrawals to keep his hedge fund solvent. The groupthink that gripped everyone else, from mortgage lenders to bank traders to rating agencies, was too pervasive to be overcome by institutional incentives.

Never attribute to malice that which is adequately explained by stupidity, goes the saying. If scientists can’t avoid p-hacking their own clean and simple data, it’s too much to expect of bankers to decipher their doom in the entrails of MBS prospectuses.

Moral hazard is also an unavoidable result of the principal-agent problem. Banks exist for the benefit of their shareholders, and bank shareholders lost more than 80% (!) between the peak of May 2007 and the nadir of February 2009. Why didn’t the shareholders make the banks figure out that MBS are too risky to invest in? Shareholders can only influence the board, which directs the CEO, who manages several layers of directors before getting to the risk analysts whose job it is to figure out MBS. If that person didn’t do their job in 2007, expectations of a bailout likely had little to do with it.

The second argument against bailouts is that they put Washington in bed with Wall Street. This is really a naive argument. Bailout or no bailout, government and finance aren’t just friends with benefits, they’re conjoined twins.

Most of what governments do is a financial coordination problem: taking money from some citizens and redistributing it or spending it on collective projects. For as long as banks have existed, governments used them for those purposes. In July 2015 the UK government finally finished paying off government liabilities arising from investments in the South Sea Company in 1720 and loans taken to finance wars in 1754.

As for banks, the government isn’t only their largest counterparty but also the provider of the legal system that underpins finance, the issuer of regulations, and the ones who actually print the money. There no finance that stands apart of politics, and no politics that is independent of finance.

So what to make of all this? Moral hazard and Washington-Wall Street incest exist with or without bailouts. Bailouts certainly don’t make these two issues better, but there’s value in the government providing the confidence that banking requires same as it provides any other vital infrastructure.

I think that some sort of government backing for the financial system is good in theory. In practice, since having a sane and informed national conversation on bailouts is impossible, we ended up with the worst of all worlds.

What happened in 2008/09 is that the actual bailout turned out to be an order of magnitude larger than the bill Congress voted on, it was lied about and covered up by both politicians and bankers, it made the too-big-to-fail even bigger and more failure prone while simultaneously undercutting more prudent competitors, and it destroyed public confidence in the financial system instead of reinforcing it.

I don’t think that anyone actually aimed for this outcome. Instead, in the absence of consensus or even dialogue, the politicians, bankers, and the Fed just followed their instincts and short-term interests. There are no guaranteed ways to succeed in finance, but gut-based short-termism is a guarantee of failure.

And yet, even after that fiasco, the financial system keeps chugging along. Houses get built, mortgages get paid, retirees retire. No matter how bad that bailout was, I’m still not sure the counterfactual is better.

Experts and Equity

The financial system is not perfect but it’s not terrible either, and I don’t think we could redesign it from scratch to improve it without risk. If we have ideas on how to improve it, we should try them out carefully and incrementally.

But maybe I just don’t have enough degrees in economics to figure out a better system to coordinate money flows across continents and centuries. Quite a few people with the requisite number of degrees seem to think it’s easy.

Anat Admati and Martin Hellwig are professors of economics, and they wrote The Banker’s New Clothes, a book about what’s wrong with the banking system and how to fix it with “specific and highly beneficial steps that can be taken immediately”. John H. Cochrane is a professor of economics at Chicago, which is like being a professor of economics but more so. He wrote a review of the book that appeared in the Wall Street Journal and on my Facebook wall with a ringing endorsement.

The central problem, at the core of Anat Admati and Martin Hellwig’s “The Bankers’ New Clothes,” is capital. In order to make $100 of loans, a typical bank borrows $97—from depositors, from money-market funds, from other banks, or from bondholders—and sells $3 of stock, its “capital.” So if only 4% of the bank’s loans fail, the shareholders are wiped out, and the bank cannot pay its debts. […]

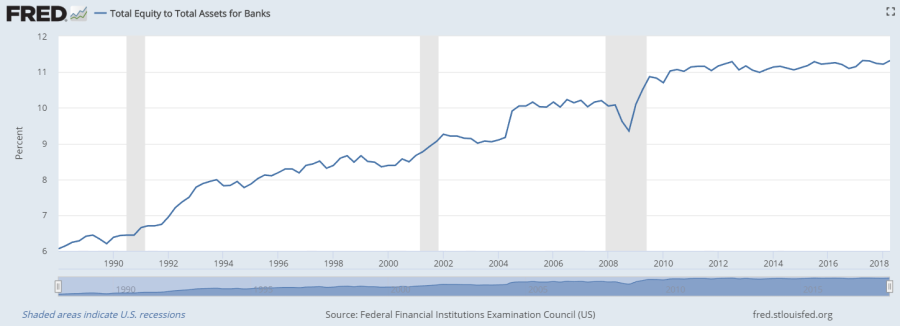

Three eminent professors explain that the problem with banking is that the typical bank holds enough equity to cover only 3% of its assets and that this number is falling. As Cochrane was writing those words, in March 2013, the average equity ratio of US banks was 11.2%, up from 6% in the late 1980s.

Let me repeat that: economics professors who wrote a book about how raising equity ratios will solve the problem of financial crises got the actual equity ratio for banks, a number that is publicly reported and easily googlable, wrong by a factor of 4. You can’t make this shit up.

Unless you’re an economics professor, in which case you can make up whatever you want:

What about those “tough” new capital regulations that you keep reading about? They are not nearly as tough as you think. At best, the new Basel III international bank regulation agreement calls for a 7% ratio of capital to assets by a leisurely 2019 deadline. But that is the ratio of capital to “risk-weighted” assets. Risk-weighting is a complex system in which some assets count less against capital requirements than others. A dollar of mortgage assets might count as 50 cents, but it might count as 10 cents or less if it is a complex mortgage-backed security, and zero if it is government debt. When Ms. Admati and Mr. Hellwig unravel those “risk weights,” we’re still talking about 2% to 3% actual capital.

Do you keep reading about new capital regulations? I bet you don’t.

You know who else has not done any reading about the new capital regulations? John Cochrane.

How can I tell? Because every single number he quotes in that paragraph is wrong.

Why do I know that? Because my job since 2013 was turning the tough new capital regulations into software and helping banks implement them. If you want to do some reading about capital regulations they are all listed on the Federal Register. But you don’t have to, I have the entire thing memorized.

Let’s see if I can rewrite that paragraph:

At worst, the Basel III agreement calls for an 8% ratio of capital to assets, while allowing national regulators to impose 2.5% on top of that. The 7% ratio is for a specific subset of capital, an extra requirement to provide extra security. This has been fully implemented in almost all major jurisdictions, including the US, between 2013-2018. Risk-weighting is a not-so-complex system, even Jacob could figure it out. A dollar of mortgage assets counts as 50 cents only if it adheres to strict prudent loan standards, it counts as a full dollar otherwise. If it is a complex mortgage-backed security it might count as much as $12.5 (a 1250% risk weight) unless it’s a very safe senior tranche.

In any case, the average ratio of capital to risk-weighted assets in the US is above 14%. This is true of all the “too big to fail banks” as well. You can find this number if you’re curious by looking at the FR Y-9C report for each major institution on schedule HC-R Part I line item 43.

Cochrane concludes:

This simple truth has been met by howls of protest and layers of obfuscation and derision by bankers, their consultants and many of their regulators. “Oh, you just don’t understand the complexities of banking” is the basic attitude.

I’m sure that professor Cochrane understands very well the complexities of banking. I’m just afraid he doesn’t understand the simplicities, such as how to look up a bank’s capital ratio online.

Ok, so maybe Cochrane misrepresents the views of Admati and Hellwig, and maybe those have changed since early 2013. I was excited to find out that a few weeks ago Dr. Admati went on EconTalk to chat with Russ Roberts, a careful thinker, skeptical interviewer, and, of course, a professor of economics.

Anat Admati: But what I see, I see the symptom of heavy indebted and distressed: there’s no companies as indebted as banks. I mean, they have single-digit equity in a good day, relative to total assets.

I agree that 11.2% isn’t a very double-digit number, but it’s still a double-digit number.

Anat Admati: They will have the story, ‘Yeah, yeah, yeah–we didn’t have enough equity and we figured that out and now we have more.’ But, I mean, the ‘more’ is like the smallest tweaks–it means nothing. The ‘more’ is like in Martin Wolf’s world, tripling zero. Which is still zero.

In the space of 15 minutes, we went from “single-digit” to “basically zero”. I’m sure Russ will call her out on that.

Russ Roberts: That, of course, encourages banks to be very leveraged, to have very little skin in the game; as you point out, to have, say 1% in equity and 99% borrowed.

Maybe there’s an upside. If all those econ professors really think that banks have a 1% or 3% equity ratio then it’s sensible to say that raising that number to 7% or 10% will ameliorate a lot of risk in the banking system. Unfortunately, in contradiction to all logic, the lower someone thinks current ratios are they higher they think they should be. Admati and Hellwig propose 20%-30% and mention the good old days when banks had 50% equity. Cochrane thinks we should go to 50% or 100%. And Roberts:

Russ Roberts: Right. Because we can’t just–it was too risky. So, that incentive is going to always be there when powerful people have a chance to be bailed out. They are going to get bailed out. So, it seems to me that those of us who understand those incentives should call out and say: ‘Well, given this reality, the only way to deal with this is to have very low levels of leverage; very high levels of equity.’ Which is what you’ve come out for.

Anat Admati: Yep.

Russ Roberts: Now, that, to me, you can debate–and I know you have–whether that’s got a cost or not. I don’t really care. The cost of it is small compared to the costs of the ongoing failures of the financial system that happen.

If I had to summarize the main lesson of 400 hours of EconTalk episodes in 4 words, they would be “everything is a trade-off”. When Roberts says “I don’t care about the costs” without thinking for even three seconds what those costs may be… there’s something about this topic that seems to incinerate the sanity of anyone who approaches it.

So what are the costs of making banks hold more capital? Let’s put a number on it.

Let’s start with a simple model: a bank has $10 of equity, it borrows $90 of deposits (liabilities) at 2%, it and lends out $100 (assets) at 5% for a 10% equity-to-assets ratio. You can review the basic accounting equation if you’re not familiar with the terminology. Let’s say that the bank has operational costs that are 1% of assets (the cost actually doing the work of taking deposits and making loans) and that 1% of the bank’s debtors don’t repay their loans.

We can calculate how much money the bank makes.

Costs: 1%*$100 operational costs + 1%*$100 borrower defaults + 2%*$90 interest paid = 1 + 1 + 1.8 = $3.8.

Revenues: 5%*$99 interest received = $4.95.

Total profit: 4.95 – 3.8 = $1.15 of profit on $10 of equity. That means that every dollar of bank equity earns 11.5% return each year, which is in line with most other industries.

What would happen if a bank had to hold $50 in equity and take only $50 in deposits to cover $100 in loans?

Costs: 1%*$100 + 1%*$100 + 2%*$50 = 1 + 1 + 1 = $3.

Revenues: $4.95.

The bank made a profit of $1.95, but that profit is divided among a lot more shareholders. Each dollar of equity has earned only 1.95 / 50 = 3.9%. This is a measly return, 3 times less than what shareholders were earning with a 10% equity ratio.

Perhaps shareholders will take a slightly lower return in exchange for a safer investment, but they wouldn’t take one-third. To get back a reasonable return on equity, instead of borrowing at 2% and lending at 5% banks might have to borrow at 1% and lend at 8%. Of course, there are a lot fewer borrowers and lenders willing to make that deal. A lot of lending will not get done: companies won’t get started [2], houses won’t get bought, investor cash will remain stuffed in mattresses.

In fact, that’s what will happen if capital requirements are raised. Equity investors will pull their money out of banks and into more profitable enterprises like apple polishing. Most banks will shut down, and the remainder will serve the greatly reduced loan intermediation market. In the good ol’ days of 50% equity ratios, even white people had a tough time getting a mortgage.

The argument for capital requirements is that banks holding too little equity impose a negative externality on everyone else in the form of systemic risk from banks blowing up. This argument runs into the puzzle of banks holding 6-7% more capital than is required of them, but it’s probably correct as a general principle.

Ideally, then, regulations should set capital requirement at the point they would be if that externality was entirely internalized by the banks. That’s what the 8% number is aiming to do. It’s physically impossible to make bankers have 100% skin in the game and still do banking, so the regulations aim to set limits that would make banks behave as if that was the case.

Of course, everyone “knows” that regulations are a scam. Admati and Hellwig promulgate the idea that corrupt regulators go easy on banks in order to get a cushy job in the industry. From Cochrane’s review:

And, in an all-too-short chapter on “The Politics of Banking,” they show us how politicians and regulators like the cozy cronyism of the current system. […] Regulators commonly become sympathetic to the interests of the industry they regulate, which advances their careers in government or back in industry.

Unfortunately for this story, research shows that tougher regulators have an easier time getting jobs in finance than regulators who go easy on banks. Think about it: if you’re a bank, would you hire the diligent and exacting Fed employees, or the lazy and careless?

On EconTalk, regulation is simply dismissed out of hand:

Anat Admati: I think that Basel, the way it was coming into the crisis was a spectacular failure. And I can just tell you how many things were wrong with it. And that what they called a ‘major revision’ was really just tightening a few screws. But it really didn’t improve it that much. And it remains this game of, you know, of playing around with the risk weights and finding ways to increase, you know, to kind of game it; and this whole thing; and putting it off balance sheet; and what’s called Regulatory Arbitrage–this cat-and-mouse game that continues to go.

[…]

Russ Roberts: How much Triple A, and weights, and how much of each kind you can have. And that whole hierarchy of, that infrastructure of supervision, monitoring, regulation, and implicit promise seems to me to be an utter failure. There’s no reason to think that that’s a good system.

I know more about the hierarchy of supervision, monitoring, and regulation than all but perhaps a hundred people in the United States. Almost all of those people, including me, are making their money by helping banks comply with the rules in letter and in spirit rather than by helping them evade the rules and play games. The reason is simple: there are too many goddamn rules to evade them all.

Aside from requirements on the amount of capital a bank must hold, here are just the regulations that I’ve dealt with in the last five years:

- Liquidity coverage ratios, ensuring that banks have enough cash flow to pay their short-term debts even in a liquidity crunch.

- Single-counterparty credit limits, ensuring that no bank is overly exposed to a single institution that will drag it down if it fails.

- FDIC 370, ensuring that even if a depository institution fails it will repay all of its deposits immediately.

- Net stable founding ratio, country exposure reporting, stress tests, special rules for insurance companies, for broker-dealers, for funds, for swaps, for qualified financial contracts…

The last thing I’m worried about is that I’ll be out of a job because regulators decide to give banks a break.

There is really just one glaring problem with government regulation of banks – it’s too nice to the government. The US government decreed that US treasuries have a risk-weight of 0%, that they’re considered a highly liquid asset on par with cash, that the government is exempt from single-counterparty limits, and so on and so forth. Every major European and Asian regulator does the same. The only way banks can comply with all the regulations is by being massively exposed to government debt in all its forms. Did I mention conjoined twins?

If nations and taxpayers bear the burden of bank risk, banks are no less exposed to government risk. Governments print the money, banks move it around, and if you find this arrangement distasteful consider that it has underpinned the global economy since long before the industrial revolution.

Conclusion

To wrap up:

- The financial industry moves money between those who have it to those who have a good use for it, which makes everything possible from tortillas to tortoise toys.

- Moving around debts is risky if you can end up holding the wrong end of it, and it’s impossible to fully control or eliminate those risks.

- Regulations do some of it, but they’ll never eliminate the possibility of crises.

- Making banks hold 100% equity will eliminate the risk in the financial system by eliminating the financial system.

- Governments and finance have been intertwined since both were born in their modern form. It’s hard to tell whether this is a feature, a bug, or a law of nature. I lean towards the latter.

If you think it’s easy to design an alternative financial system without banks or the governments by repeating the word “blockchain” a lot, I have some Jacobcoin to sell you. And if you think it’s easy to fix the system by replacing the carefully crafted system of financial regulation and oversight with a 50% capital requirement and a ban on bailouts, you’re almost certainly an economics professor, and you’re almost certainly wrong.

[1] The top earners in finance do make a lot of money, but the average “banker” doesn’t. Median hourly wage in the finance and insurance sector is $25.10, compared to $31.43 in “Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services” or $29.51 in information and communications. The financial industry is made up of a lot of average people earning an average salary putting in honest effort into average spreadsheets.

[2] Early on in FedEx’s history, its founder needed $27,000 to fuel the planes and save the business from bankruptcy. After failing to get just one more bank loan, he flew to Vegas with his last $5000 and miraculously made enough to save the company, pioneer overnight shipping, and make things like Amazon Prime possible for millions of people. Somewhere a great company is closing its doors because the bank that would give it the loan is running up against its capital limits.

This was a super interesting post, thanks! To push back a little: Your case for RMBS is compelling, but presumably you can conceive of a financial instrument which might do more harm than good? Like, say, CDOs so hideously complicated that no-one understands them, and even the supposed experts assign them AAA ratings? Obviously everything is a trade-off, but the mere fact that a market exists for any given class of product doesn’t necessarily mean it has a net-positive impact.

In other words: unless you’ve somehow run the numbers on the value produced by weird derivatives, and offset it against the costs of the global financial crisis, maybe the level 1 brains are actually right? If the trade-off is really tricky to calculate, it might be best to invoke the precautionary principle?

Your broader point about finance being massively underrated is really well made. I’ve dunked on the banks a lot over the years (banking/consumer affairs reporter) but I hope I’ve become a bit more even-handed as I’ve learned more about this sort of stuff.

LikeLike

The problem then isn’t with the securities, but with the “experts” giving them AAA. Also, this problem is self-correcting.

The rating agencies fucked up the rating of MBS so badly leading up to 2008 that everyone collectively decided not to trust them anymore. The risk-weighted assets rule explicitly removed any mention of ratings, banks must now rely on their own models and regulator-provided buckets, whichever is more conservative. This cost the rating agencies a lot of money since there’s less demand for their dubious services.

Most financial innovation is beneficial, but there’s almost certainly at least one thing happening in finance today that’s a bad idea. If you can figure out what it is ahead of time, you can make a lot of money. If you can’t, you’ll have to outlaw all financial innovation to stop it, and that still won’t completely prevent crashes.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“The problem then isn’t with the securities, but with the “experts” giving them AAA.”

I’m struggling to put my finger on why this doesn’t seem like a good argument, but it’s something like a lack of pragmatism: we live in a world full of flawed individuals and institutions. As much as we might wish we lived in a different world, this is not going to change any time soon.

It reminds me of the classic libertarian line: in theory, smoking or 40oz soda cups or unfettered access to assault rifles are good, because they allow people to satisfy their preferences. They certainly create a lot of value, even if it’s fuzzy and difficult to calculate. If people overindulge, or shoot up a school, well, the problem can hardly lie with the gun/soda/cigarettes. In practice, I’m glad to have my hands tied on these kind of things. We have to look at the evidence of what happens, not what ought to happen.

If most financial innovation is beneficial, but occasionally it misfires and causes massive destruction on a global scale, that seems like an extremely good reason to be wary of bankers and their clever new instruments.

I read this post as saying that no matter how wary we are, regulation can only do so much, and bad things will inevitably happen anyway. You’re probably one of a handful of people with enough knowledge to make that judgment, so I’ll defer to your expertise. But I don’t think it follows that the general anti-bank sentiment is wrong (even if some of the specific claims are). Dangerous things are still dangerous, even if we have limited ability to make them less dangerous.

LikeLike

The point I was trying to make with Banksy and the corn cobs is that the value created by the financial industry outweighs the harm caused by the crises. It’s just harder to see, while the harm is very obvious and sudden. People lost their jobs because of the crisis, but a robust banking system is what enables (among other things) a lot of modern jobs in the first place.

The baby is worth more than the bathwater, and you can’t drain any of the water out without tossing the baby.

LikeLike

Gotcha. I agree that the baby is worth more than the bathwater, and your post made me update even further in that direction. I’m still not convinced about the second half of that sentence, but I don’t know anything about the specifics, so my intuition is probably leading me astray. Curious to see reckons from other finance insiders. Thanks for such a thought-provoking post!

LikeLike

“The problem then isn’t with the securities, but with the “experts” giving them AAA.”

Because it identifies (and avoids) a single point of failure. When people believed that Moody’s or S&P could properly rate a (poorly understood) security, it standardized the price (okay – it classified the risk, which then allowed a standardized price). If each individual investor (bank, hedgie, fund manager, pension fund, whomever) has to delve into the CDO2 or MBS we will get a range of views on their risk, and thus a spread in price – which conveys information. It also means that each investor will have to more carefully weigh their risk acceptance, and make a deliberate choice, rather than just buying a rating.

There will be an important second-order effect, too: Setting up the rating agencies as arbiters of worth 1) allowed increasingly complex securities, since most investors never looked at the underlying, only at the rating 2) put pressure on the agencies to deliver a rating – even when they couldn’t properly assess the risk. That set up a perverse spiral, with issuers getting more and more aggresive on structure, stetching the agencies’ (and the issuer’s) ability to predict performance and riskiness, when the agencies interests were just in maintaining deal flow becasue that’s how they got paid. Forcing each investor to do their own due dilly will put pressure on complexity: we can’t rely on the geniuses at Moody’s, so we had better understand what we are buying – and complexity represents (potential) risk, which will be priced into the bids for the next great innovative security.

LikeLike

‘Banks exist for the benefit of their shareholders’

This seems like a major crux. Most anti-finance people I know would say that ‘corproations exist to enrich their execuives’ is an important model. As you describe in your post shareholders only have an indirect ability to influence policy. Shareholders lost 80%+ but how did bank executives do?

LikeLike

I also think this post sort of implicitly conflates too different critiues of ‘finance’. Your post is called ‘in defense of finance’ but its mostly about critiques of banking. Your defense is good and many people do want to impose much stronger regulations on the banks. But imo the strongest ‘burn it down’ propossals are not aimed at the banks.

I am personally relatively ‘anti-finance’ but I don’t want to get rid of banking or ‘lending with interest’ more generally. I am not even against institutions offering options. It does make sense for a factory that depends on aluminum to be able to hedge against aluminum prices increasing.

What I am sympathetic to burning down is ‘trading’. As far as I can many large firms provide essentially no exra value compared to investing in index firms. You have made some arguments before that places like Jane Street improve the economy by reducing bid/ask spreads. I am a little skpetical the benefits of these firms outweighs the profits the capture. But there are some very large firms like Captial group that are almost certainly a worse bet for their customers than buying index funds. It seems like a kind of crazy coincide that a firm that is not trying to help the world and is not really helping its own customers happens to contribute positively to the world economy. Notably the customers of firms like Capital group includes a substantial amount of large pension funds and the public may wind up essentially footing the bill for the fees Capital Group charges!

If new regulations might disrupt lending/banking I would be concerned. But I would not lose much sleep if new regulations made trading less profitable. I am a sort of libertarian guy so I am not particularly big on stopping people from wasting their money. And obviously you need some amount of trading for price discovery. But I don’t think the ‘price discovery’ argument justifies modern Wall Street. And I would be happy to make hedge funds and other traders substnatially less profitable via tax reform.

Overall I think the post is pretty convincing and informative. but its a really a counter to some, admittedly very common, misinformed critiques of banking. It doesn’t really defend modern finance as a whole. In addition the logic of the post really seems to rely alot on a certain pessimism that change is possible. You basically admit the bailout was, at best, very shaddy. But your basic position seems to be that we are never going to be able to disentangle the corrupt partnership of poltiicians and bankers. This may be true but its not exactly the most rousing defense of the finacnial system.

LikeLike

I am going to defend large profits from trading.

For the record, I am a consultant whose clients are all multi-billion dollar hedge funds.

Large profits from trading occur primarily when you know something of great significance that other people don’t.

There are other ways to make large profits from trading that are less beneficial to society, but these are distraction from the primary case, like using “welfare queens” to smear all social welfare programs.

There are two ways to know something important that other people don’t: you are privy to insider information or you go out and do fantastic research and exploration. We have regulations to limit the former kind of profiting.

In the end, large profits from trading provide incentives for people to discover high-value information.

For example, short-sellers are often the first to discover that a company is feeding a false narrative to the public, and their profits benefit society by stopping the flow of massive amounts of capital to companies that are misusing it.

Distressed debt investors are the flip side of short-sellers: the social benefit of making a large profit in distressed debt is a result of restarting the flow of capital to companies that people mistakenly think can’t use it.

Traders earn a fair profit, from society’s perspective, by correctly guiding society to better capital allocation.

LikeLike

I dont think this is true, or at least it is not true without substantial caveats: “Large profits from trading occur primarily when you know something of great significance that other people don’t.”

I mentioned two large companies by name and think they are somewhat represenitive of two important categories. One category of companies mostly make profits by charging fees on products that are no better than index funds. They are basically selling financial homeopathy. Its not snake oil because their products are not really worse than the market on average if you ignore fees, but its expensive homeopathy. I think Capital Group mostly falls into this category.

The other category is the small set of companies that probably are ‘beating the market’. Lots of these companies, including Jane street, are basically trying to execute ‘arbitrage’ strategies. That is they are trying to find and exploit pricing inconsistencies. In particular they are looking for inconsistencies in relatively complicated financial products. Making derivatives markets slightly more efficent does not seem like it provides a ton of value. I agree it provides some value but Jane Street profits may exceed the value provided. [disclaimer Jane street strategies are not exactly made public and I don’t have any inside knowlege]

LikeLike

Can’t speak to the value of all business models. Quite likely Capital Group is overcharging its clients. Closet indexing (running what is basically an index fund with large fees, claiming to have “special sauce”) is an activity I view as unsavory.

As to Jane Street, arbitrageurs, and high-frequency trading: that is a profitable sector in the medium-term as we adjust to new technology in finance, so I consider that a matter of this moment in time, not finance in general.

The folks I work with tend to be extremely research intensive. That is something that has been of value for decades and something I expect to always be of value. The traders I know who make large amounts of money do it by dint of better research and insight.

80% of the rich (in the U.S.) got there by adding value to society. 20% got there by scamming society. I believe that at least 80% of trading adds value. The 20% that may be scam-driven provide endless anecdotal evidence that people get rich by scamming society. But, even if we allow that 20% of wealth is gotten by scams, I believe people getting rich by trading is a net positive to society.

LikeLike

What non-public information would you need to know to determine whether Jane Street’s profits exceed the value that it provides? Suppose I tell you exactly what their strategy is, how would you then calculate whether their profits exceed the value provided or not?

LikeLike

Social value provided is never a cut-and-dried manner. That’s why we have politics: to have a discussion about what is of social value.

There are three cases: the social value provided is obviously positive, obviously negative, and unclear.

I would tend to hew to a simple rule-of-thumb that if the social value of something is not obviously negative, we should leave it alone, otherwise we will quash what may turn out to be value that we simply don’t know how to measure.

LikeLike

I wrote an essay on this a year or two back (http://seekingquestions.blogspot.com/2017/10/whats-point-of-capital-markets.html). Main points:

– Finra is really, really terrible. “Self regulatory organization” are the magic words. Pensions and other funds get ripped off as a result. But that’s pretty specific, and could probably be fixed without wrecking the whole finance industry.

– I’d guess price discovery has pretty small value at the margin; it’s a second-order effect.

– Various abstract forms of warehousing are probably the main real value add from finance.

LikeLike

Interesting argument about warehousing. I wonder how one could try to quantify it.

LikeLike

First step, for any attempt to quantify the real value of finance, is to go look at where all the capital ends up. I researched that a bit at one point, sooner or later I’ll get around to writing it up.

LikeLike

I think it’s very hard to separate “good finance” from “bad finance”. It’s like saying “let’s get rid of the most annoying 10% of species in this ecosystem, no one likes them” and then you’re surprised when the entire ecosystem immediately collapses. Funds need brokers who need banks who need insurance companies who need funds and so on forever.

Look at Scion Capital, Michael Burry’s hedge fund. It’s the part of the industry you think is least justified: a proprietary trading firm charging investors high fees to look for arbitrage. But Burry buying credit default swaps on mortgage CDOs probably made Goldman realize what’s happening and started unwinding everything. If not for Scion Capital, the party could have gone on for another year or two and the crash would have been much worse.

Finally, I’m pessimistic about interventions, but I’m optimistic about organic change. Look: we mostly figured out MBS now. There’s going to be another crisis, but MBS won’t cause it. No one is going to think anymore that resecuritizing junior MBS tranches makes them AAA safe. From this day on we can have all the benefits of MBS with a lot less downside.

Finance gets better crash by crash, and it does get better. I just don’t think it gets better by following the advice of economists who can’t google.

LikeLike

How exactly do you propose that we “burn trading down”? There are a lot of problems with everyone just owning the index- not only the price discovery issue, but also issues of competition and corporate governance. There’s already a fair amount of econometric evidence suggesting that high passive ownership in the airline industry has led to higher fees by reducing incentives to compete. This is most likely a general problem. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2427345

Even setting aside the societal issues with “too much index investing”, there’s also the issue that individuals often have valid reasons to prefer different distributions of returns. For instance, someone who works at Microsoft and has a lot of Microsoft RSU’s probably doesn’t want the rest of her portfolio to be “the index”- she most likely maximizes her expected risk adjusted return by overweighting assets that are less correlated with Microsoft stock. If all publicly available financial services are geared only towards facilitating the purchase of “the index”, she seems significantly worse off than she would otherwise be. (Though to be fair, firms like Cap Group probably wouldn’t help you here unless you were wealthy enough to qualify for an SMA).

I do think that there are certainly good arguments for higher taxes on speculation. One idea that I’ve had is to tax excess returns at a higher rate than market returns- i.e. if your stock portfolio has returned 20% annualized when you liquidate and the market only returned 12%, then you pay a higher tax on all excess profits beyond the 12% you get by buying the index. But I’m sure there would be some kinks that would need to be worked out with the implementation.

LikeLike

In practice I am in favor of something a different commentator wrote: ‘Since we can’t rebuild, maybe a solution is to start disentangling the system and trimming the fat (banning securities of dubious interest) wherever possible. It’s grunt work, but it might be highly beneficial. Of course, one would need a special mandate, or actor’s incentives will still get in the way.’

Though I am definitely in favor of doing things that would dramatically cut finance profits. In particular I am in favor of laws preventing pension and other public funds from investing in managed funds.

LikeLike

Agreed that there’s a lot of people being fleeced by active trading strategies (and retail brokerages that persuade them to be active traders themselves). Maybe anielsen’s billion-dollar hedge funds are actually beating the markets net of fees for their investors, though I’m skeptical of that–but I’m much more sure that any active management product an average Joe or his pension fund can buy is a waste of money.

My suggested reforms for this are pretty milquetoast, though–there should be an equivalent of the ‘Surgeon General’s Warning’ on all managed funds and retail trading platforms explaining the broad economic consensus in favor of index funds for individual investors. And all defined-contribution pension plans should be required to have an index-fund option, and when employees get the choice they have to read that same Warning. Also they have to play a recorded version of the Warning before every episode of Jim Cramer.

LikeLiked by 1 person

For the record, I absolutely agree with you regarding consumer-oriented active-management products.

The investment advice I give to anyone in my personal life who asks me is to stick with index funds, focus on extremely low fees (Vanguard, Schwab, etc.), and use a simple allocation across no more than 7 funds roughly approximating the world economy.

Most people need set-and-forget investments that allow them to sleep at night.

Just as there are innumerable junk food products, there are innumerable junk finance products. While getting rid of junk food would be wonderful, doing so at the price of eliminating food altogether would be fatal!

LikeLike

Also, I think the price/time priority rule might disproportionately reward high-frequency trading.

Consider a textbook arbitrage scenario: a bunch of S&P 500 member stocks’ prices all fall due to trading. That means the price of S&P 500-tracking index funds should also fall, but that fall doesn’t happen by magic–it happens because an arbitrageur will start selling them at the new, lower price (based on the calculated value from the component stocks). So far, so good.

But most securities exchanges use a price/time priority rule that gives priority to the first orders placed at a new best price. So if you’ve spent crazy money to wring every bit of speed out of your computers and data links and can be the first trader to put in a sell order at the new price, then your order will take priority over everyone else’s, no matter how many others have put in sell orders at that same price before the first buyer comes along.

But remember the social value of all this comes from providing good prices to buy-and-hold investors. And from a buy-and-hold investor’s perspective, a new best price being set a microsecond earlier only matters if your trade actually executes in that microsecond.

In short, traders are rewarded for being first to a new best price in proportion to how long that price remains the best, but they only create value in proportion to how much they beat the next-fastest trader to the price by.

I’m not sure how much of the returns to HFT are actually accounted for by this, but the possibility is right there in the rules.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, learnt a lot. Being professor myself, I find it depressing that professors in elite institutions can make elementary errors and no peers take them to task for that. But then it is all too familiar.

LikeLike

Can we see a source for the FedEx Las Vegas story? A quick Google didn’t turn up anything.

LikeLike

I forgot to add the link, so I did a quick Google of “fedex founder vegas” and got it :)

https://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/10/15/fred-smith-blackjack-fedex_n_1966837.html

LikeLike

I think, broadly speaking, there are 3 main things that cause people to think of banks differently than other businesses.

Central importance to the economy.

If Johnson & Johnson went bankrupt it would suck but the economy would keep going. If the largest bank went under it could trigger an economy killing chain of events a la 2008.

High degree of abstraction in operations.

I have a theory that the more abstract the work of a business (or job) the less people like/trust it. Modern banking is highly abstract, especially if we broaden that to modern finance.

“Too big to fail”

It is not unreasonable for someone to mistrust something that is declared so big it has to be protected. I think if the big banks had been “broken up” (even if just on paper) people would have emotionally handled the bailouts better.

Add to those the years of anti bank propaganda in pop culture and its easy to see why even smart people can have weird knee jerk reactions to the subject of banks.

LikeLike

I appreciate what you’re trying to do and was hoping to be challenged, but sadly I wasn’t convinced.

What I think you’re not taking into account in the first part of your argument is the massive complexity of the financial system.

The exemple you give are simple and obviously desirable / beneficial. Of course we want lending and trade.

The MBS case is already less obvious. Why is it a good thing to allow investors to bet on mortgages? Shouldn’t bank decide individually on which mortgages to grant?

One good argument: by emitting these securities, differenciated by risk, banks are able to grant more mortgages than they would otherwise be inclined to. These mortgage will have higher interest rates, as is natural: bigger risk, bigger reward.

The problem here is that of incentive. Since the banks (or whatever agent grants the mortage) make money out of selling these securities, they are actually encouraged to grant more and more risky mortgage and to classify them as less risky than they really are. That’s just the principal-agent problem, and it’s exactly what happens in the lead-up to 2008, afaik.

(In theory, that’s why you have a credit rating organism, but again, incentives and complicated relationships/co-dependencies between agents made that moot.)

But I believe this is vastly more complicated than that. I mean, even in my meager investigation of stock purchase, I’m surprised at how much hidden complexity there is. I’m lead to believe financial instruments are much, much, much worse. To the point, oft repeated, that no one really understands how it works.

That’s probably incidental complexity. At least, at first. Then the opacity of the system becomes a feature. Again, the principal-agent problem strikes. As deluks also said, executives did get richer. They were incentivized to sell whatever made them a big bonus. And they knew themselves secure: they didn’t have more skin in the game than losing their jobs if the system went bust. But everyone else was doing it anyway. The system would have gone bust with or without them.

I don’t think executives necessarily knew that the securities were bad. But the point is: they didn’t want to know. I think it takes some weirdo contrarians to actually get to the bottom of these things. Most people won’t do that when it could threaten their bonus and/or their situation (if you know, you have to bring it up, or a posteriori it could be shown that you knew).

The system may have started with good intentions but incentives and complexity/opacity derails it very fast. I think this is what people don’t like about finance.

If we could go clean-slate (which let’s be clear, we can’t), wouldn’t it be much easier to just allow well-reasoned things that are beneficial. Your corn cobs elder are not a realistic model – I think one can make a convincing argument that trade and lending brings value. If you come up with some new financial mechanism and you can’t make a compelling argument that will convince scientifically-minded types that it will be a good thing, and think maybe one ought to not accept it.

My main point: of course well-understood parts of finance are useful. For some of the very complex parts (overly complicated derivatives come to mind), that is quite dubious to begin with, and incentives combined with complexity will lead to “problems”. You don’t make a strong case that these murky parts of the financial system are necessary, besides “it’s complicated and we probably couldn’t rebuild it better from scratch” — which is a statement I do agree with, it’s just not a very good defense of a the financial system as-is.

Since we can’t rebuild, maybe a solution is to start disentangling the system and trimming the fat (banning securities of dubious interest) wherever possible. It’s grunt work, but it might be highly beneficial. Of course, one would need a special mandate, or actor’s incentives will still get in the way.

I know the standard critique of people who think like me is “legibility” (as in Seeing Like a State), and while there is some of that, it’s always been my impression that it’s much more applicable in highly-social systems than in systems that are more prone (in-principle at least) to formalization.

I don’t have an opinion on letting banks fail, or jailing top executives. But moral hazzard is real. If you don’t change the incentives, the situation will happen again. Shareholders and top executives might not have been the real perpetrators, but they had the power to change incentives for the lower echelon.

The last part of the article was very interesting, and opposed a lot of pre-conceptions I had!

Keep up the good work :)

LikeLiked by 2 people

John Cochrane may be wrong about many things, but there is at least one thing he knows that you don’t: the Modigliani-Miller theorem.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Modigliani%E2%80%93Miller_theorem

This makes your argument about “So what are the costs of making banks hold more capital? Let’s put a number on it.” approximately 100% wrong.

Now, it still is better for the banks to keep their capital low, because this reduces taxes (on their capital sources) and their debts are cheaper due to being effectively subsidized by the expectation of bailouts.

But neither of these benefits for the banks makes the public benefit from low bank capital.

LikeLike

I forgot to mention, there is also a “lemon problem” where a bank that raises additional capital might be assumed by investors to be in trouble. This is an additional reason for banks to keep their capital low when not forced to raise it but it doesn’t make even the banks lose anything from being required to raise it by regulation.

LikeLike

By ” taxes (on their capital sources)” I meant the total of tax on the bank and on their sources of funds including debt.

LikeLike

I don’t think that’s correct. The valuation of the company may be the same regardless of leverage, but that does not guarantee the profit margin or anything else will be the same.

Also the theorem’s proof is either unclear or false as written on that Wikipedia page. Say company L is financed by $1 billion in loans and $1 billion in equity, and U has $2 billion in equity. I could pay V_U and then take out $1 billion in loans; I would then own U, $1 billion, and $1 billion of liabilities. Alternately, I could pay V_L, and then I would own L and its $1 billion of liabilities. By stipulation, U and L are equivalent goods, so V_U = V_L + $1 billion. I do not think I have found a puzzle that eluded the Nobel Committee and 60 years of economists but it sure looks like I did.

LikeLike

How do you measure the value of the profit or whatever else? In present terms it adds up to the value of the company so that is the correct thing to be comparing.

Referring to your second paragraph, I agree that the theorem is not especially clearly stated on Wikipedia. Where V_X is market capitalization of X, it is indeed the case that V_U = V_L + $1 billion. U has more share value but is no more more or less expensive to buy when you consider that you can borrow money to buy it and end up with the same amount of debt as buying V with cash.

LikeLike

Now, if you could also explain why high-frequency trading isn’t just parasitic I would possibly stop finance hating for a while.

LikeLike

They improve price accuracy for the long-term investments that are more directly valuable. (https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpwps/ecbwp1602.pdf)

LikeLike

The total profit made by all high frequency traders put together is less than a billion dollars a year and falling. Relative to the financial industry as a whole, that’s not a large number, and I suspect (but cannot prove) that the higher liquidity and slightly improved price accuracy is worth it.

LikeLike

Could you explain the MBS more to someone who knows almost nothing about finance?

This is what I got:

Bob in Seattle and Alice in Minneapolis and Carly in Tampa all buy houses. And then somehow their mortgages are all combined into an MBS. Does this mean they will all be writing their mortgage checks to the same bank, say Wells Fargo? Or can mortgages to multiple banks be wrapped into one MBS package?

Then what happens to the MBS? Do Zeke and Yvette each purchase a piece of the MBS through eTrade? Does only financial institution buy them, like Chase buying 20% of Wells Fargo’s MBS? You said that buying a piece is equivalent to betting that at least X% of the mortgages will get paid…if 1 or more of the mortgages don’t get paid, how does that loss get distributed among MBS holders?

LikeLike

I think a major crux here has to be what you think about finance’s role in recessions. If you buy some version of the conventional story about Wall Street crashes causing Main Street unemployment, you probably have a case for some regulation.

On the other hand, if you think Scott Sumner knows what he’s talking about and competent central banking can easily insulate the broader economy from an asset crash, this is a non-issue. (c.f. http://www.themoneyillusion.com/fannie-freddie-and-the-three-crises/)

LikeLike

I thought your summary of finance in general was good. I wonder if we could change the nature of savings and checkings accounts to make it less easy for a run on banks to happen, and more appropriately represent that money. Make something like “flexible bonds”– because if a customer’s money is active and is being lent somewhere else and they’re getting interest to reflect that, then it would be reasonable to show that. Granted, interests rates are artificially low right now so IDK.

I massively disagree with the bailouts! The bailouts were not a cheap way to manufacture confidence, because the chronology of the bailouts was chaotic. First there was the bailout of a few specific companies (Bear Sterns, Fannie&Freddie, AIG), then the $700 billion. It led to executives waiting to sell off their bad assets, because they were holding out on the chance of selling them for an insane price to the government.

You should read Tom Woods’ chapter on The Great Wall Street Bailout from his book Meltdown: http://www.riosmauricio.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/Woods-Meltdown.pdf

If you’re saying that the finance & political system is too complex and anti-inductive for any mortal, then that means really means anyone! So the bailouts were done by bumbling mortals too, with no actual idea of how to fix it. So unless the Fed is run by hyper-intelligent quasi-immortal lizardpeople, we’re just wasting money and distorting market signals. Here’s an except from Meltdown that shows Henry Paulson’s failure to tackle the complexity:

LikeLike

“Manufacturing confidence cheaply” applies to governments backing banks in general, I agree that the specific case of last bailout was the opposite of that.

There’s sort of a catch 22 here. If governments could set up a bailout beforehand, that would manufacture confidence cheaply. Something like announcing that in case of a crisis, any bank could borrow up to 10% of its assets from the government at Fed rate + 5% for five years. But governments can’t do that because voters would cry “OMG we have corrupt bailouts in the law now!”, which means that bailouts can only be done in moments of panic, which means instead of cheap confidence we get panicked and terrible bailouts.

Everyone, and I mean EVERYONE, is dying to know what the bailout policy will be at the next crisis. No one does. This is dumb.

LikeLike

It’s nice to finally see a post where a number is put to something. I still see that you’re trying to explain how people who come to a different conclusion then you do think. You should stop. You’re not good at it.

I want to withdraw from the social contract. The only way I know that I could do that is through suicide which I refuse to do but the social contract is not working out well for me. I understand that I serve some value to society (and I can guess at what that is) but it’s still not an arraignment that I’m happy with.

I acknowledge that many people who work for finance work long hours at a stressful job in a highly completive environment. All these things are bad for humans. The culture of the financial industry that finds this acceptable is a reason to be critical of the financial industry but this situation is hardly restricted to the financial industry. I do have sympathy for these people.

There are, however, people who work in finance for which the social contract appears to be working out very well. Also, the financial industry does engage in practices that generate money for individual people without contributing anything of value to society (what social benefit is there of buying and selling the same thing over and over again thousands of times a second?). The financial industry does some things that have a social benefit and some things that have a social harm.

Given that in a roundabout way the luxury of the captains of finance is due in part because of my suffering, given that the captains of finance earn some of that luxury in a way that is socially neutral or harmful, given how arrogant and contemptuous of people like me captains of finance have been in recent memory, and given how government have bent over backwards in recent memory to keep captains of finance in luxury while I go hungry then yeah, it should not be surprising that I have a negative emotional reaction to the financial industry.

And yes, I am mature enough to understand that having a negative emotional reaction to an institution and having legitimate reasons to seek changing it are different things but they’re not incompatible. Yes, I understand that you support government redistribution that would significantly improve my quality of life but this does not change the reality that the financial industry will continue purchasing laws for its benefit while a basic income guarantee is, for now, a pipe-dream. Also yes, I do change how I talk about the financial industry when I’m making a not-completely-serious statement off the cuff in an informal environment and when I am making serious criticism.

But, a large part (though not all) of my emotional reaction can be accurately (though not precisely) summarized as “bankers are bad because they’re rich and I’m not.” Since this characterization can reasonably be made, any concerns of mine about the financial industry no matter how trivial or significant, how thought out or spur of the moment, how serious or humorous, can be dismissed as mere envy and a personal failing of mine and not in need of any further engagement.

And I believe that you do not openly think such a thing. This is what you opened you post with, however. The first eight paragraphs are insulting people who could possibly have an emotion reaction because they’re unsatisfied with the current material wellbeing no matter how much they struggle and see people getting rich through finance (partly) in a way that makes their lives worse.

The emotional reaction is understandable and should be respected. The point that the financial industry does more benefit then harm and that it is structured such that it is imposable to remove harm without removing even more benefit is a good debatable point. Stating that the financial system is so vast, important, and complicated that nothing should be done to reduce the harm and/or increase the benefit through government action is less of a good point.

Having a 0.1% tax on all stock market transactions would have a significant effect on the financial system and its practices. If one holds a stock over the course of months, the 0.1% tax would be a triviality (I think, I’m not exactly sure, the .1% number isn’t the end goal) but if one holds a stock on the order of tens of microseconds then it would be a big deal. This I believe would incentivize more investment behavior and less speculation behavior while not significantly harming the ability of the market to respond to new impactful information about a company. Even a serious proposal of such a tax would change behavior.

Am I expert enough to know if this is overall a good thing or a bad thing? I am not. I do think that it can stand serious conversation and consideration by decision makers. I don’t think this change will completely wreck the financial industry if it’s enacted much less if it’s debated. I do think it makes for a remarkably poor rallying cry. I think, “I’m going to really stick it to Wall Street,” is a much more effective way of getting ones message across then is “Your three cent titanium tax doesn’t go too far enough.” Living more than three decades around Washington DC I am also aware that the bill or the regulation that imposes a 0.1% tax would be crowed as “sticking it to Wall Street.”

There are numerous other suggestions about how to “fix” the financial industry. Some of them are to completely remake the system and some people legitimately believe in these. Many of the suggestions are similar incremental changes. As someone who generally supports incremental change in everything in the short run (even if I want large scale change in the long run) I don’t think my ideas of how to change the financial industry (such as proposing a 0.1% tax on every trade in a registered stock market exchange) are going to wreck society.

If one politician makes lots of nebulous noise about how they’re “going to take on Wall Street,” or how the “financial industry is running roughshod over the American people,” and they get elected then they have some pressure to do something for which they can show actually has an impact on realigning the incentives in the financial industry with the public good.

If a second politician has a record of speaking privately to financial institutions and talks about making some minor incremental changes then I fully expect this politician to make some reform of the laws governing the financial industry (or merely making a proposal then giving up) that on the surface might look like it’s taking on the financial industry but really is a massive benefit for the companies who can hire the best lobbyists to write the law.

If I want to actually achieve minor incremental change in how the financial industry operates then I am better off supporting the politician who is talking about major wholesale change then the one talking about minor incremental change. (Putting aside, for now, the question of how much one’s vote, or campaign donation, or canvasing really matters, or the ability for a single legislator to actually change things).

As far as my emotional reaction to the financial industry: it is legitimate and deserves respect. Rationally understanding an emotion of mine isn’t negating the emotion or pretending that it doesn’t exist: it’s allowing it to exist in its appropriate place. I get angry at a driver who I think is being rude to me on the highway. I can respect that anger without allowing the anger to dictate my actions (most of the time). The rational reaction to my emotional dislike of the financial industry is to understand why I have the emotional reaction so that I can make intelligent decisions. My dislike comes from understandable reasons and is a legitimate emotional reaction and by respecting it, I can determine how much it controls my actions.

For example, you work in the financial industry and I don’t dislike you. I like you on an emotional level. To the extent your job has long hours, is stressful, and is in a highly completive environment, I have sympathy for you. I do dislike it when you are cheerleading for Yudkowsky rationalism or when you attempt to explain the thinking of people you disagree with but I’m disliking your writing, not you. And even this diatribe is an attempt to help you (and maybe also to vent some frustration).

Once again, I don’t think you have an actual dislike for people who disagree with you (at-least just because they disagree with you) or that you will be insulting once you know you’re talking with someone who holds a particular position. We all lose sight of the variety of thought that exists. I will ask you a question and want you to answer it for yourself (I don’t care if you tell me or others the answer but I do want you to come up with an honest answer for yourself). When you made or chose the graphic that mocked the attitude of “bankers are bad because they’re rich and I’m not,” did you think that this attitude should be treated with respect or with contempt (or some other reaction)?

Other points:

Really? REALLY? The vast majority of people think that de jure slavery is a bad thing that should be outlawed. A majority of people who live both north and south of the demilitarized zone in Korea (much less people in the rest of the world) would rather live in the Republic of Korea then in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea. The vast majority of people think that the sun feels warm and that ice feels cold. The vast majority of people who know what prime numbers are think that 41 is a prime number. I could go on.

Now, one could change the statement to “This urge is so strong that it is nearly impossible to find an issue on which people disagree where people up-and-down different levels of education and left-and-right on the political spectrum agree with each other.” This is a trivially true statement and thus imparts very little useful meaning.

On the vast majority of all possible issues people could potentially disagree with, the vast majority of people do agree with each other. There might be a very small minority of people who truly disagree on each of these but we all agree more then we seem too specifically because the interesting conversation tends to happen on topics on which people disagree.

No matter how large the Overton window actually is, it always appears to be the same size. I, never the less, maintain that, in terms of American politics, the Overton window is narrower than it ever has been. I full heartedly disagree with your statement here.

I am going to first make an argument about why nobody ever gets paid for risk and then I’m going to make an argument for why risk (in a certain sense) is all anybody ever earns money for.

I know defenders of the financial system, or high executive compensation, or whatever say that people are making money by taking risks. It’s a popular belief amongst a group of people but it comes off as self-motivated justification that may or may not have any connection with reality. That’s not the point. It seems that people say this in order to convince themselves they’re still good people. Whatever. I don’t really care about that aspect but this explains why such declarations aren’t convincing.