Successometer

Since I was a kid, I have built my self-esteem on a feeling of “forthcoming greatness”. Whatever I actually accomplished I never paused to be proud of, and I never sweated the failures either. It was all just a stepping stone to something completely different and undeniably awesome, a “life mission” that will be important and meaningful and finally confer on me the title of #SuccessfulPerson. Until that moment came, I just needed to know that I was growing, progressing, improving, optimizing.

But upon entering my second gigasecond I’m starting to realize that this mindset makes little sense going forward, and was perhaps delusional in retrospect as well. But if I give up on rapid improvement and impending awesomeness, I don’t know what can possibly replace them.

By all objective metrics, I’m as successful today as I could hope to be a decade ago. I’m happily married, well inside the richest 1% globally, have found my tribe and earned some respect in it. I should be able to relax and take some satisfaction in my current situation. And yet the thought that in 5 years my life will look exactly like it does today fills me with dread.

What’s the problem? Jordan Peterson’s fourth rule says: compare yourself with who you were yesterday, not with who someone else is today. I do both, and both are a problem.

I seek to be inspired by awesome people, but it is then inevitable that I compare myself to them. There could be many blogs that are worse than Putanumonit, but I don’t have the time to read them. I read SlateStarCodex and the very best curated articles from elsewhere, and in comparison to those Putanumonit seems quite shabby. Offline too, one of the main perks of success is associating with successful people. Being involved in the rationality community in NYC means I hang out with Spencer Greenberg, who runs an Effective Altruism startup foundry while doing social science research and innovative meetups in his spare time — making me feel less than impressive.

But that’s not even the main issue. I’m never jealous of other people’s success for one, and I know that the people I look up to probably feel inadequate when they read about Elon Musk. It’s the comparison to who I was yesterday that’s more insidious.

Comparing myself to my old self means that my internal successometer measures only the derivative of my life’s trajectory, not my actual situation. This means that as I improve and achieve things it becomes ever harder to maintain the pace of personal growth that makes me subjectively satisfied. The better I do the lower my successometer goes, and more I am tempted to chase “new challenges” like quitting my job to start a company. I don’t even have a great idea for a company, and there’s certainly nothing wrong with my day job, it just feels like the only option to keep that part of my psyche satisfied.

The Buddha tells me to relinquish this drive and the illusion of forthcoming greatness. After all, there’s no guarantee that this mental state is actually helping me succeed, rather than just making me restless and unhappy for no reason. But since right now it’s still part of me, the threat that I may lose my drive to improve and optimize scares me out of trying to simply drop that sentiment. At the very least, I would have to replace it with another framework for making sense of my life, past and future.

But what could that be? Who would be against striving, optimization, and excellence?

Mediocrity

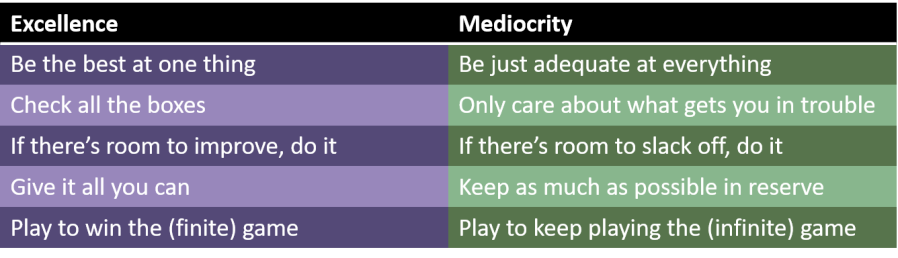

Survival of the Mediocre Mediocre is almost good enough to betray its own thesis. Venkatesh Rao defines mediocrity not as middling performance on some well-defined measure, but as a general resistance to well-defined measures and their siren calls of optimization. Instead of rewriting the essay, which you should read anyway, here’s a low-effort summary of the differences between excellence and mediocrity.

Excellence reaps rewards in measurable achievement and works best for winner-take-all well-defined competitions. It is also what earns public admiration because it is legible. An athlete excels at a particular sport gains many fans even if they are atrocious performers in every other area of life like relationships, personal finance, or being able to read.

Mediocrity, on the other hand, helps survive unending scrambles like evolution by natural selection. Rao gives the examples of avian dinosaurs, mediocre by the standards of both dinosaurs and modern birds, who survived the Cretaceous extinction by flapping around mediocrely. Mediocrity gives you optionality and the slack to adapt to new opportunities and challenges.

Unfortunately, mediocrity is never satisfying. Before the asteroid hit, the proto-birds couldn’t know that it was coming, and couldn’t feel superior to the majestic apex predator dinos. And after the cataclysm, they don’t get any credit either — the mediocre always appear merely lucky and opportunistic from the outside.

Rao treats mediocrity or excellence not as immutable qualities (although for a dinosaur, they are) but as intentions, stances one can adopt towards life. Before deciding which one to commit to, let’s see which one has worked for me so far in life. Here’s my excellent biography:

I got into the best high school in Israel and by age 15 was already taking college classes in math. At 16 I was a certified tennis instructor and started making money coaching. I competed in national math Olympiads. I joined the most selective non-combat unit in the Israeli military for my service and pursued a dual degree in math and physics. After the military, I joined a hedge fund and studied for the GMAT in parallel which got me into a top-20 business school in the US. Then I came to New York, got a job at a successful financial company, and started a successful blog.

So aspirational. Much excellence. Very optimizing. Wow! How can this be the life story of a mediocrity?

I was in a good high school and put so little effort in that I was almost expelled in 10th grade. My spare time was mostly spent playing soccer and card games with friends but a few of us managed to study and pass a special simplified university entrance exam. Despite taking a fraction of the regular university course-load, my grades were always close to the median and ultimately it took me 8 years to finish my BSc from the day I started. I was the worst tennis player by far at the instructors’ academy and passed because a teacher took pity on me and gave me 15 minutes to demonstrate a left-handed serve. I placed 3rd in math Olympiads. I was dismissed from the most selective non-combat unit in the IDF for, I kid you not, “not striving for excellence”. I completed my service in a down-to-earth technology division where my peers were all officers while I remained a sergeant. I joined perhaps the most pointless hedge fund in Israel, got no training, made no profit, and left shortly before the entire company shut down. I got rejected by 6 out of the 7 business schools I applied to. I came to NYC because I failed to secure a full-time offer after an internship in a big company Atlanta. My job is in financial regulatory software, a lucrative niche without fierce competition. In 2015 I was part of a client engagement so dysfunctional I had literally nothing to do for days on end — so I started Putanumonit. While Spencer Greenberg’s blog is literally called Optimize Everything, mine merely encourages the reader to put a number on it. It doesn’t even have to be the best number, whatever works is fine.

Which narrative is true? I think they both are. Reflecting on my life honestly, I have to conclude that a lot of my success is due to lucky circumstance. But also to a combination of mediocrity and excellence. The common motif of my life is ambling along without too much focus and determination, noticing an easy opportunity that I have the slack to exploit, and then summoning quality effort when it’s needed: passing entrance exams, building the product that established me at my company, writing the post that launched Putanumonit.

This is what Rao calls “mediocre mediocrity”: being just OK at being just OK. My life is mediocrity interspersed with occasional outright failures (the army unit, the job in Atlanta) and occasional bursts of excellence.

Unfortunately, even with this awareness, it’s very difficult to commit to mediocrity. What if I just slack off for years and neither opportunity nor asteroid shows up? Do opportunities even happen to people after 30? Perhaps after a gigasecond of exploration, this should be time to exploit, to pick an important project and pursue excellence. But which project?

The Project

It’s quite likely that the most important pursuit of the next decades of my life will be parenting. And ironically, I think that the best way to parent is to be a deeply mediocre parent.

I’m not the first person to notice that Something is Wrong with Kids These Days (TM) and to tie it to an almost pathological drive by parents to optimize childhood. Helicopter parenting. Snowplow parenting. Tiger moms. Academically tracked selective preschools and elementary schools where 6-year-olds chant “We are college bound!” in unison. Something is wrong, really wrong.

And it’s not just wrong for the kids, it’s wrong for the parents too. Parents are sacrificing every bit of slack they have to give their children one more unasked-for advantage, driving their child to a slightly more prestigious violin teacher who lives half an hour further away. And once a parent has sacrificed money, time, their social life and romantic life, it’s is very hard to accept that your child is, merely a not bad violin player. He may grow up to play bass for the rock band at the local state college! Ma’am, why are you crying? Ma’am?

There’s a lot of evidence that all this optimized child-rearing does not make children any more optimal, only miserable. Mediocre parenting isn’t guaranteed to produce excellent children either, but it should at least be a lot more fun.

I don’t know if I’m ready to commit to mediocrity wholeheartedly, to give up on striving and optimizing and feeling unsatisfied. But writing this self-therapeutic essay at least makes it seem less scary, a viable life strategy. And perhaps I never get to choose mediocrity, it chose me a long time ago.

The general problem seems to be that if you have to “strive for excellence”, the odds are already against you. There are plenty of people who strive for excellence by simply already excellently fulfilling each and every facet of excellence required in their field of excellence. The world probably has enough population that every slot for greatness can be filled by people who are naturally inclined for that slot. And I can’t think of too many greatness slots that are best filled by people who spent years overcoming akrasia.

The best way to become a concert pianist is to start at age 4 and never question or waver from it. The worst way to become a concert pianist is to start reading Less Wrong at age 24 and developing the optimal training-and-self-motivation regime for becoming a concert pianist.

You don’t get booted for “not striving for excellence”, but for not having the right excellence to begin with.

(I feel that EA has transformed from a group of people who were striving for excellence, into a group of people who simply are excellent. Maybe it’s for the better, but I suspect something may be lost in the change.)

LikeLike

“Be just adequate at everything” is virtually a synonym for adulting. Adulting is being competent at a vast array of not-very-hard skills, ranging from car maintenance to banking & investing to keeping your house tidy to managing functional relationships with your family, neighbours, friends, and co-workers.

LikeLike

This hits so close to home that I can’t even understand my emotional response to it.

Of many, some potential choices:

* Invitation to just accept the mediocre aspects of my self.

* Another invitation to recommit to pursuing excellence in something.

* A statement about the dual nature of the world where everything is nothing and both sides at the same time. (A bit like order and chaos)

* An urge to deny your reality, “this really is excellent to me.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve found good experiences with generalist skills. It’s not so much “mediocrity”, though it might qualify as such in Rao’s meaning of the term. It’s having the ability to draw from a wide range of domains, and apply them in ways that more specialized people can’t.

For example, I’m a financial planner. And most of my high-impact work recently has been coding. I’m not even an especially good coder (I’m okay, but not the best in my department, let alone the company or world), but I have the subject matter expertise to know what we need to do, the skill to be able to implement it, and most importantly the vision to know how to connect the two. (And I get pissed off at shoddy work, which helps produce good results.) Most of those skills are not unique, and a few I’m actually pretty meh at. But the combination is unique, and so a bunch of my co-workers call me “Einstein” unironically. What I do isn’t even all that impressive most of the time, but I actually make it happen, and nobody else has the personality and skill set to do that.

The best coder, best project manager, and best financial planner in my department could not, between the three of them, produce some of these things. They wouldn’t have a good start-to-finish view of the problem, and the high communication costs would make it cripplingly difficult to get things done. But I’m mediocre enough to be the right man for the job.

LikeLike

You’re talking about something slightly different, which is also very interesting. Here’s a good post about the math of getting to the Pareto frontier by a combination of skills, and why it’s better to try to be the best at some combination of skills than at a single one.

But the mediocrity Rao talks about doesn’t mean “middling performance on some spectrum”. It’s more about hearing the phrase “Pareto frontier” and running the other way.

If I tried to be excellent, it’s clear that I would do it by looking for a project that requires some combination of math, writing skill, humor, and financial knowledge or somesuch. And that would be the opposite of mediocrity.

LikeLike

This article reminds me of Scott Adams book “How to fail at almost everything and still win big”.

It’s all about building a large set of mediocre skills, while optimizing your energy and trying a bunch of things till you succeed.

LikeLike

Comment from the previous generation. Opportunities do happen to people after 30, even after 60. Some of the most creative and satisfying of them are indeed related to parenting. What’s more – you are getting better in recognizing opportunities (after squandering some previous ones).

I end with personal confession: when you were too young to make decisions himself, despite your precociousness, I’ve resisted multiple calls to bring you to the guy preparing kids for winning math Olympiads. After all, I want my kids to be happy; whether excellence in something is needed for that, they decide for themselves (I personally do not need it to be happy),

LikeLiked by 4 people

I know it’s a cliché but I’ve never been so tempted to say “Are you me?” before, because this exact thing bothers me daily. Thanks for helping me see how not-alone I am.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hey Jacob – this might be my favourite of your articles so far, probably because it hit so close to home (and I happen to know a bunch of other people struggling with the same thing). I’ve been thinking there might be an inescapable trade-off between impact in the world and satisfaction/experiential happiness. The reductio version would be a monk sitting on a mountaintop in meditative bliss forever. OK, he’s Zen as fuck, good for him, but he’s not exactly doing much to make the world a better place.

Lately I’ve been cultivating the mediocrity mindset in low-stakes domains, and man, it feels so good to be content with ‘good enough’. At the same time, I’m still striving and doing the whole self-flagellating thing in other areas, because I feel a strong sense of duty to actually contribute something to the world, and not be an entirely lazy and self-interested asshole.

I perfectly fit your definition of ‘mediocre mediocrity’. At some point down the track, it’ll be a relief to embrace that wholeheartedly, rather than pretending to be anything else. But not just yet!

LikeLike