Academic moral philosophy is paradoxical. It’s consists of carefully argued articles, but morality is usually least concerned with what a person can argue for in a paper. Ethics are about how we act in the world, in context, around other beings and their preferences. But the main tool of academic moral philosophy are thought experiments devoid of context, other actors, or real stakes.

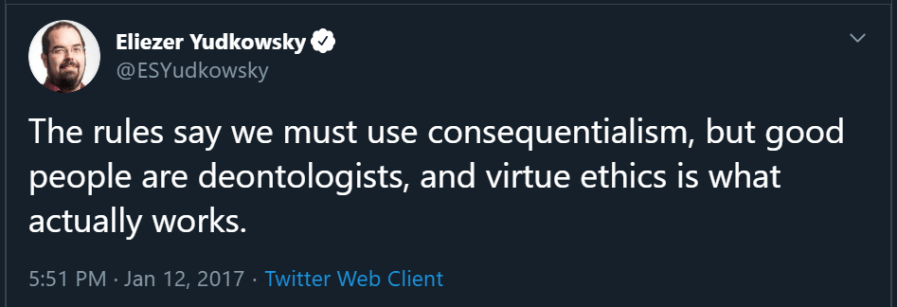

At best, after studying moral philosophy for many years one is successfully inoculated against further moral philosophy and ends up here:

So what better tools can we use for thinking about ethics outside the confines of our current lives?

In my last post about video games I wrote about their evolution from mere gameplay, to wrapping the gameplay in a story, to delivering the story through fully actualized characters who have their own goals and motivations. When these align or conflict with the goals and motivations of the player, games can ascend to new levels of immersion and meaning.

This makes video games a wonderful arena for exploring morality. Video games create a world in context, populate it with other character, and invite you to make choices and act. The best games entice you to do things not for the sake of a high score but because “it was the right thing” or “it’s what the character would do”. They invite you to think about ethics.

This post will cover 4 of my favorite 5 games of the PlayStation 4 era, with a focus not on the gameplay or the story but on the system of ethics experienced through the games. (Four, because Horizon Zero Dawn is about transcendence and divinity, not ethics.) I’ve read books and taken classes on ethics, but I’ve thought more and learned more about the subject while playing the games below.

Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain — Bronze Age Morality

There’s a plot in MGSV:TPP, but I have no idea what is. It’s because:

- It was hallucinated by Hideo Kojima.

- It has practically nothing to do with the game.

In the actual game you play a legendary soldier (Big Boss) who assembles an army of special soldiers to fight a variety of regular soldiers and super-soldiers. The game takes place in the late eighties in Afghanistan and Angola/Congo, two places chosen solely for the high concentration of military action taking place there.

Through the game, when you encounter enemies that are easy to kill you simply kill them. But when you encounter skilled enemies you do everything in your power to keep them alive. Big Boss shows special affection for the sniper Quiet not because she is good looking and half-naked (he has more erotic tension with his male friend Ocelot) but because the mission where she tries to kill him is one of the most difficult and rewarding in the game. Boss’ enemies repay the favor in turn, refusing to kill him despite being offered many easy opportunities to do so.

At first I thought that everyone’s adamant refusal to fill their most dangerous enemies with lead is simply stupidity for the sake of the plot, but that’s not the case. Every character in the story was made for combat, knows only combat, loves only combat. If you kill your enemies, you wouldn’t get to enjoy fighting them again. Everyone’s worth in the Metal Gear universe is determined solely by their skill in battle.

This system of values is lifted straight from The Illiad. Achilles is hot headed, violent, greedy, and prideful. And yet, he was revered as a hero in Bronze Age Greece for the sole quality of being very skilled at killing people (and by implication, for being favored by the gods). Achilles doesn’t sail for Troy because he cares about politics, loyalty, Helen of Sparta or women in general; he lusts mainly for young boys, and loves only Patroclus. He sails to Troy because (like Afghanistan) that’s where the fighting is, where he’ll get to kill a huge pile of Trojans and die gloriously on the battlefield.

After being suppressed by Christianity for two millennia, Bronze Age warrior ethics is making a comeback as an esoteric philosophy, most recently, in the batshit but entertaining Bronze Age Mindset. And this morality is fully encapsulated in The Phantom Pain. No matter how often its creator keeps saying that the game’s message is anti-war, war is the only system of value the game has.

Red Dead Redemption 2 — Communal Morality

The hero of RDR2, Arthur Morgan, is conflicted. He seeks to do good in the world while riding with a violent gang of outlaws. He tries to stay loyal to both the man who raised him and the man he mentors, even as the conflict between the two escalates. RDR2 could have tried to forge synthesis from this conflict. Instead, it choose to be a schizophrenic mess.

The first sign of the game’s confused ethics is that it has a literal sliding gauge of your moral standing. Help out a stranger, and a white icon informs you that you gained “honor”. Pop a cap in a fool’s ass (or just run them over by accident) and your moral balance slides toward the red. And then you play a story mission with your gang where you massacre entire towns for a few dollars and see your “honor” rating budge not one iota, because narrative-sanctioned slaughter doesn’t count.

While this seems absurd on it’s face, I think that RDR2’s moral approach is quite realistic as befits a game fanatically devoted to realism. Arthur Morgan has never read a book on moral philosophy, but very few people have. In lieu of a rigorous system of ethics most people follow local social norms, copy the people who seem respected, and in general outsource any moral thinking to the surrounding community. There is no good and evil, only what is commended and what is reprimanded.

By and large, this works perfectly well until the moment when separate worlds mix together and their norms clash. Until the gang robs an innocent traveler, or the debts they collect ruin a family’s life. Until someone’s juvenile tweets spill into their real world career, or their locker room talk makes front-page news. Red Dead Redemption gives the player plenty of room to think about this problem, even if it stops short of offering real solutions.

The Last of Us — Survivor Morality

7 minutes into the zombie outbreak that kicks off The Last of Us, Joel and his daughter Sarah are trying to escape town in his brother’s truck. They see a family begging for help at the side of the road. Sarah and Joel’s brother want to pull over, but Joel intervenes: What do you think you’re doing? Keep driving!

The game proper begins 20 years after that day with most of humanity is dead, including Sarah. Equally dead are sentiments like honor and justice, along with the civilization they served to uphold. Now there’s only protecting your own, and killing to avoid being killed. Those who were slow to adjust perished. Those quick to adapt survived. Joel took 7 minutes.

The game starts when Joel meets young Ellie and is charged with taking on a cross-country trek. She rekindles in him the love he felt for Sarah, 20 years before. But Joel is never confused about living in the new moral world rather than the old.

The Last of Us is the best written game of all time. Bad stories have many voices and zero characters, while a good novel can tell a single character’s story well. The Last of Us delivers two compelling character arcs at the same time: Joel’s Odyssey to reach a safe port with Ellie and escape his past, and Ellie’s journey to independence.

Bad movies have childish morality, better TV shows have anti-heroes. But The Last of Us offers a twist on a twist: Joel, the main character, is clearly not a good guy. But the game challenges the player: who are you to judge him?

<spoiler> The final scene of The Last of Us presents a classic Marvel-esque dilemma: sacrifice one person to save the world. And while Ellie is ready to give her life for the cure, Joel is ready to shoot up an entire hospital of good guys to stop her from doing so. And he does. And I hated it. At least, I hated it for the first few days that I spent thinking about the game. But I’ve been thinking about it for years now.</spoiler>

Another conflict at the heart of academic moral philosophy is that it tries to construct moral truths that are universal across space and time, based on moral intuitions that are contingent on transient and unusual circumstances. Kant talked much about universal imperatives and argued that children born out of wedlock should be killed. No one can escape moral provincialism.

Take a basic premise: killing is bad. Can’t get more obvious than that. But how obvious is it?

In a Malthusian scenario, otherwise known as the normal state of most living things throughout history, it’s hard to see what’s particularly bad about killing. Every deer not hunted in the fall is one more fawn that will starve in the spring. Is it better to starve than to be eaten? On the other hand, imagine a world where all diseases are cured and people live forever in communal bliss. How much worse is murder in that world than in ours, with our finite life spans and prevailing hardships? Will the people of that utopia consider a death in our world to be as tragic as we do?

The Last of Us takes place in Boston and Colorado, not a fantasy world of magic or a distant planet. But it asks the player to go farther than most games, into a world beyond our limited local ideas of good and evil.

The Witcher — Doing Good in a World of Hypocrites

The game. The show. The books.

My first noble deed. You see, they’d told me again and again in Kaer Morhen not to get involved in such incidents, no to play at being knight errant or uphold the law. Not to show off, but to work for money. And I joined this fight like an idiot, not fifty miles from the mountains. And do you know why? I wanted the girl, sobbing with gratitude, to kiss her savior on the hands, and her father to thank me on his knees. In reality her father fled with his attackers, and the girl, drenched in the bald man’s blood, threw up, became hysterical, and fainted in fear when I approached her.

— The Last Wish, Andrzej Sapkowski, fantasy writer

I have this joke that I wish one of my three daughters would work for a profit. Because–you know, somehow they were acculturated, I think, to take the view that working for a non-profit is inherently morally better than working for a profit. And therefore, that’s what you should do. That’s an interesting point of view. I mean, it’s an interesting heuristic. Now, as an economist, I’d say the heuristic is: To a first approximation, the most socially useful thing you can do is the thing that pays the best.

— EconTalk, Arnold Kling, economist

“God is dead”, said Nietzsche, and with him humanity’s source of values. Therefore mankind must set itself a new goal — that of the Übermensch. The super-man will master all of human potential and surpass everyone in his ability; he will create new values based on a lust for life and love of this world.

“I don’t believe in the gods”, says the witcher Geralt. He has lust for life, and for women too. He has surpassed everyone in fighting ability, but whose side should he fight for? Deciding what is good and what is evil is the Überwitcher‘s great challenge.

Geralt’s world is full of people talking about morality. Kings talk about divine right and loyalty, warring races justify their savagery with appeal to universal laws, knights talk about honor as they feud with priests who talk about faith, a mage and a princess invoke consequentialism to convince Geralt to murder the other. And whenever someone starts philosophizing about morality Geralt (and the reader) can safely assume that they are full of shit.

But it doesn’t mean that these people are evil, just that they are hypocritical. Hypocrisy pervades every aspect of the witcher’s world. People criticize mercenaries, magic users, and sex, while doing everything in their power to get some coins, a spell, or laid. And yet, Geralt tries to help them as much as he can.

Economics can be described as the science of how people get what they value, and Geralt takes the economist’s view of the world around him. Instead of paying attention to what people say, he looks at their revealed preferences: what they’ll pay for and what they’ll give up, what they’ll fight for and what they’ll sacrifice.

People react poorly to economists holding a mirror to their hypocrisy. Robin Hanson discovered this when he confronted leftists about focusing on the only the most convenient kind of inequality. Geralt discovered this in Blaviken.

But while Robin continues to get in trouble for calling our hypocrites, Geralt decided to adopt their tactics. He pretends not to feel common emotions so that he can make moral decisions in a levelheaded way. He cites a non-existent witcher’s code because, in his own words, “those who follow a code are often held in high esteem”.

And I think that’s another way to read Robin Hanson’s work, or that of Robert Kurzban. They would say that hypocrisy is as endemic in our world as in Geralt’s, except that real people may be even more refined in the ways they hide their lack of morals behind platitudes and virtue signaling. But hypocrisy can also be the tool of a hero who wants to do good without having to give up sex, beer, or getting paid. Geralt is the economist’s hero.