On the last day of my MBA’s finance class, the professor admitted that very few us are ever going to use the formula for return-on-debt in our lives. Instead, for that class he gave us a single sheet of paper titled “Bill’s simple and suboptimal personal investment guide” and explained his simple and suboptimal personal investment strategy.

In the years since I have not once used the formula for return-on-debt. I did, however, use Bill’s guide to set up my own investment account, and then one for my dad, and for my girlfriend, and for a couple of friends… and now I’m going to do the same for you.

A few disclaimers before we start:

- I am not a certified investment advisor. In fact, I’m not a certified anything at all. Don’t sue me.

- This guide is suboptimal. You can open your own brokerage account and replicate the ETF structures to avoid the 0.15% Vanguard fees, but I’m not going to tell how to do that because see point #1 above.

- This guide is simple. A lot of people I know don’t invest their money at all because they think the entire universe of finance is beyond the grasp of mere mortals. I am going to start with some very basic concepts, which it turns out are all that is needed because investment isn’t actually that complicated. If you’re familiar with the basics and agree that diversified index funds are the way to go, you can skip the “Investment Basics” section and get to the second part where I detail my personal investment strategy.

- Personal gain disclaimer: Wealthfront is the main platform, along with Schwab, that I use for investing my money. I’ll explain the reasons for this choice later in the post. Wealthfront isn’t paying me for the endorsement (nor are they aware of Putanumonit’s existence) but the link is my own personal referral link. Clicking it gives you a fee waiver for $15,000 and me a waiver for $5,000. Wealthfront’s fees are 0.25%, so if you use my link I get $12.5 (and a warm fuzzy feeling).

- Both the platforms and investment types (e.g. a Roth IRA) I mention here are specific to the United States. My global readers may be interested in the general overview and the retirement spreadsheet, but they wouldn’t be able to apply the investment details.

Enough disclaiming. Let’s get to the FAQing investments part, starting from square one.

Investment Basics

Q: I don’t get “investing”. Why would anyone give me money just because I already have some money?

The first rule of money is that a dollar today is worth more than a dollar tomorrow. That’s because some people have ideas about taking a dollar today and doing something profitable with it. For example: a company could take your dollar, buy an apple, polish it, and sell it for two dollars. If the company doesn’t have the original $1 to get the apple-polishing industry rolling, they will be willing to borrow it from you for a share of profits (i.e. stock) or a return of your $1 plus interest later (i.e. bonds).

If you use your dollars to buy stocks and bonds, you’re investing. If your dollars sit in your checking account earning no interest, they’re worth less.

Q: Giving someone else my money sounds risky, what’s up with that?

The second rule of money is that a safe dollar is worth more than a risky dollar. This means that you get paid extra if someone wants to take your safe dollars and do risky stuff with them. Germany pays 0.3% interest on 10 year bonds because there’s a low risk of them defaulting on their debt or hyperinflating the Euro. Nigeria pays 16% because Nigeria is riskier. If they offered any less, people would buy other countries’ bonds and not risk their cash there.

For stocks, the extra return on risk is implicit. Putanumonit Inc, an apple-polishing conglomerate, has 100 shares outstanding so each share entitles you to 1% of the company’s profits. If Putanumonit is expected to earn an average profit of $50,000, you’d think that a share should be worth $500. But unlike cash, the profit isn’t guaranteed: it could be a lot more or a lot less. Every rationally risk-averse person would prefer to own $500 in cash (safe) rather than 1% of the company (risky). To sell shares, Putanumonit Inc would have to offer them at a discount – perhaps $400 each. If you buy the share and wait for the actual profit to accrue, it will end up worth $500 on average and you’ll earn a 25% return for tolerating the risk.

The rationality of risk-aversion is an important assumption for the risk-return tradeoff. There are many reasons for it, like the benefits of predictability and psychological risk aversion. The assumption doesn’t hold all the time: people are willing to hold the riskiest possible investment, a lottery ticket, for a whopping return of negative 50%. But risk-aversion holds enough that on average, as investments are bought and sold getting a high return usually requires accepting higher volatility and risk.

Q: Cool, so I can just do something crazy and risky with my money and it will make a huge return?

Nope, risk in itself doesn’t generate high returns, only risk that someone is willing to pay you for, and someone will only pay you to hold risk that is otherwise unavoidable. If you invest in Putanumonit Inc, you face many sources of risk: volatility in the price of apples, the demand for polished fruit, the value of American dollars vs. other currencies etc. The way to avoid specific risk is through diversification.

For example, you could buy stock in an apple orchard to protect against surges in the price of apples, or convert some of your dollars to World of Warcraft gold to hedge against currency fluctuations. By investing in more things that don’t go up and down in step with Putanumonit Inc, you face less volatility than if you just held a single stock.

Some risk is impossible to diversify: when the financial crisis hit in 2007-8 stocks and bonds fell in every country and every category. Since smart investors will diversify away the diversifiable risk, the remaining return on stocks and bonds should compensate people for the unavoidable.

When the risks and returns of various investment portfolios are plotted on a chart, there’s an “efficient frontier” beyond which portfolios can’t improve. The frontier represents the lowest possible risk for a given expected return, or the highest return for a fixed level of risk:

Q: Most investment portfolios are probably pretty close to the efficient frontier, right?

No, because people are stupid and don’t diversify nearly enough. What a lot of people don’t realize is that your brokerage account isn’t your only asset. Everything you own is an investment, and so are your life and career. Many people also hold stock in the company or sector they work in because that’s what they feel familiar with. But if you’re a programmer and you own tech stocks, your risk is doubled: when a tech crash happens you lose your investments and your job.

The most common example of underdiversification is home country bias: people tend to buy stocks from their own country. If I live and work in the US my livelihood already depends on the American economy doing well. If American companies tank and Chinese companies flourish, I’m not going to be able to learn Mandarin and get a job in Chengdu. The most I can hope for is to be holding some Chinese stocks when that happens.

Home country bias should be easier to avoid in 2017. Perhaps you thought it’s safe to invest in America: it’s a stable democracy whose citizens prosper because free trade allows them to specialize in high-value jobs (like blogging) and talented immigrants from around the world that keep the American economy vibrant and innovative. Then America elects a crazy person who threatens democracy and the rule of law, wants to dismantle free trade so Americans can go back to manufacturing t-shirts and growing avocados, and who harasses and bans immigrants.

Now those Brazilian mining stocks don’t sound so risky after all, do they?

It used to be prohibitively expensive to buy the stocks of thousands of companies in every industry and corner of the world. Today it’s practically free, with index funds. Instead of having to personally track down each individual stock, a behemoth like Vanguard does it just once (but with a pool of billions of dollars) and you buy a piece of the pie from Vanguard. The funds are cheap because the company creating them doesn’t make any decisions or analysis, they just follow simple rules such as buying everything in a broad category, which is what you’re looking for anyway.

People are investing more and more in index funds in recent years. What’s unclear is why some still don’t.

Q: But owning a tiny piece of everything on the globe is boring!

Excitement while investing is usually a sign that you’re losing money. Boring is good. Average is good.

This is one of my absolute favorite quotes:

Same goes for investing. If we only wished to make the average market return, this could be easily accomplished. But we wish to earn an above average return, and that’s impossible because of the efficient market hypothesis.

Q: But that’s just a hypothesis. Can’t I earn better than market returns by picking the best stocks?

No, you’re not smart enough.

Q: Can’t I earn better than market returns by picking a good fund?

No. Not only does the average mutual fund underperform the market in a given year, the majority of them usually do. These mutual funds are run by guys and gals with MBAs, and we’re just not that smart. Even if you were super smart, you can’t predict which fund will do better or worse unless you have perfect information about their investment strategies, which they’ll never give you.

Did the people in nice suits show you a strategy that beat the market by 50% last year? That’s because they didn’t show you the other one they tried, the one that lost by 55%. Did they beat the market 10 years in a row? They’re probably running a “reverse lottery strategy”, one that has a high chance of a low positive return traded off against a risk of complete annihilation. This is commonly known as picking pennies in front of a steamroller, you can guess how those strategies end. Are they investing based on the 17th monthly industrial lag?

There are very few hedge funds who consistently beat the market, but you can’t invest in them. These opportunities are rare and limited in scope, so only a limited amount of money can be invested in them. It’s easier to deal with a single investor than a thousand, so the best funds usually accept only big sums from multi-millionaires. It’s even easier to have zero investors: the very best funds usually just trade the founders’ and employees’ own money.

Having mad math skillz might be enough to get you hired into one of those, but they’re nowhere near enough to evaluate them from the outside. By the way: if my readers know of a company in NYC that’s looking for people with mad math skillz, holla at your man.

Q: OK, can I earn worse than market returns?

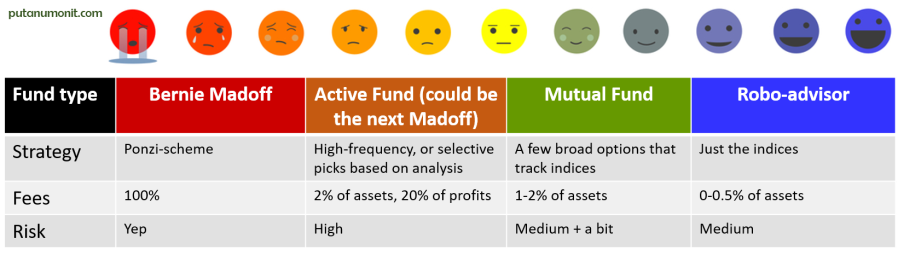

Yes, people do it all the time! Mainly, by paying investment fees and taxes. Unlike death, paying some tax is generally unavoidable. Investments fees, however, are simply people stealing your money. Fortunately, robots aren’t as greedy as people are and will invest your money without stealing any of it. That’s the main reason why I invest with robo-advisors like Wealthfront and Schwab: they use simple robotic algorithms to invest your money in broad index funds. Because they don’t have to pay the robots a salary, they don’t charge you (significant) fees.

The goal of the investment strategy I’ll outline below is to achieve the average returns of a maximally diversified portfolio while paying less in taxes and as little fees as possible. Point by point, this is what I actually do with my own money.

Get Rich Slowly – The Putanumonit Way

I make a middle-class American salary, and save more than a third of it.

There are two basic goals I want to accomplish by investing:

- In the short term, have a bit more money whenever I need it than I would have had if I left it in cash.

- For the long-term, never to run out of money until I die.

It may seem impossible to figure out how much money I’ll use up for the rest of my life, but we can put a num on it using this incredible spreadsheet that I put together in half an hour. The spreadsheet simulates investing part of your income until retirement (which then compounds), then drawing down from the investment after retirement.

Here’s how to use it:

- The spreadsheet has two tabs: “Fixed” and “Editable”. In the second one, the values in the green cells can be changed to try out different assumptions. In the first one they can’t, so you can still see a reasonable worked example after people mess up the second tab.

- It’s just a single Google doc and I have more than a single reader (hopefully), so it’s likely that several people will be playing with the editable tab at once. You should be able to copy the sheet to your own Google doc or Excel and play with the numbers privately.

- All numbers are net of inflation, i.e. they’re in 2017 dollars.

- The goal of the game is to have a positive number in the “balance when you die” cell. If the number is slightly high, your kids and loved ones get a nice inheritance. If the number is negative, at some point in the future you’ll be: A – alive, B – broke, C – cursing the day you didn’t heed the advice of my Google doc. You have been warned.

The assumptions I made in the first tab skew young and pessimistic, like I am. Two of the cells are retirement year and years of life after retirement. With Social Security running out but medicine improving, I would urge people to err high on both: assume you’ll retire at 75 and die at 115. Historically, US inflation has been around 3.3% and stock market returns have been 7% for a net return of 3.7%. My assumption of 3.5% could be pessimistic (if other countries will achieve high returns by catching up to the US) or optimistic (if we’re headed for a global stagnation), but it’s the best I could come up with. An inflation-adjusted wage growth of 2.5% is also conservative.

Under those assumptions, you can see that even a person who starts saving 45 years before they retire will need to put aside 30% of their salary. To simplify the model I made the saving percentage constant, but a better idea is to save a large percentage of every increase in income. Thus – getting rich slowly.

I save most of my raises and try to fight lifestyle inflation.

My family moved to Israel with $16. After a long while, we were able to afford a car that was a decade older than me. After another long while, we got such luxuries as a TV. The funny thing is, I never felt growing up that we were poor. In fact, I felt just the opposite. I felt rich because each year we were slightly but consistently richer than the previous year. As long as you’re not actually poor, the key to financial happiness is to get richer slowly and steadily.

In simpler terms: Happiness = Reality – Expectations, and your brain’s money-expectation is exactly whatever you just spent last year. Spending a tiny bit more this year than last year feels like living in luxury.

When we came to the US for business school, two of my Israeli classmates bought new sports cars. I bought a bicycle for $150. They didn’t live beyond their means: both are talented and successful people who can afford any car they want. It’s just that when you’ve had a Z5 it’s hard to downgrade. When I got an internship and traded my bike for a third-hand Toyota Yaris, I was as happy with the upgrade as my classmates were with theirs.

I’m doing well in an absolute sense, and a lifestyle increase of a mere 1-2% is more than enough to feel really rich. Since my salary has been going up by a lot more than that, I’m happy to invest most of my raises and by now I’m putting away roughly 35%-40% of the total salary.

I keep just enough in my checking account to cover ongoing expenses, and invest the rest.

The investment platforms I mentioned can convert your index funds into cash and send it to your bank account in 4-5 days, so you don’t need to hold more cash than you’d need on a 4 day notice. I keep about 50% more than my average monthly credit card bill, so I can pay my cards on time with autopay. Any huge unexpected expense can go on the credit card too, since I have at least 30 days to pay that back and have more than enough time to withdraw the invested money if I need to.

If you expect a 7% return on stocks, you’re losing $700 a year for every extra $10,000 you’re keeping in a bank account.

Savings accounts are a scam

A “high yield” savings account gives you 1% interest, except that your money is usually less flexible than if you invested it in a fund. Every $10,000 you keep in a savings account costs you $600 a year in lost yield, plus a headache. That $600 goes to your bank, since it immediately turns around and invests your money for its own profits, at high yields.

I have a Roth IRA at Wealthfront, a 401k at a mutual fund, and personal accounts at Wealthfront and Schwab

Let’s break down the platforms and the account types. Investment funds / brokers lie on a scale from actively managed funds that pick and choose specific instruments to automated robo-advisors that buy broad indices. The more selective a fund is, the less it’s diversified, which increases your risk. Since increasing your risk takes work, the active funds charge you fees for the pleasure.

The three large robo-advisors in the USA are Wealthfront, Schwab and Betterment.

Betterment

- Con: 0.25%-0.5% fees, otherwise same as the other ones.

Wealthfront

- Pro: Can allocate >50% to international instruments and emerging markets.

- Pro: Over 10% in municipal bonds, which are a good diversification and aren’t taxed in the US.

- Pro: Convenient dashboard that can show all your other investments in one place.

- Con: 0.25% fees above your first $15,000, this cap can be lifted by inviting friends.

Schwab

- Pro: 0% fees.

- Con: <40% international, <5% municipal bonds.

- Con: 7-20% of your investment is held as cash.

The percent held in cash is the main reason I prefer Wealthfront to Schwab for all my accounts except one. Cash holding is a hidden fee – if 10% of your investment is in cash and you miss out on 7% returns while inflation eats away at it, you’re paying 10%*7%=0.7% fees.

As for the portfolio allocation, I prefer to diversify away from the US but otherwise it’s hard to evaluate who gives you better deal. This decision can come down to personal needs. For example, the high-yield portfolio at Wealthfront holds 16% in real estate vs. 6% at Schwab. If you own a house, you already have too much of your net worth tied in real estate and should prefer to diversify away from it. When you set up a portfolio on either site they ask you a bunch of questions, such as whether you own on rent a place to live, and adjust your allocation accordingly.

As for the different investment accounts, they mainly differ in the time horizon and the taxes you pay on them:

Roth IRA

- Pay income tax when you earn the money today, but no tax when you withdraw it in the future.

- Can withdraw after age 59.5, or for some non-discretionary spending (house, medical bills, your kids’ college).

- Can invest only up to $5,500 per year.

401k

- Pay income tax when you withdraw the money, but no tax when you earn it.

- A bit less flexible that Roth for non-discretionary emergencies, and also must start withdrawing at age 70.

Personal investment

- Pay income tax when you earn it, capital gains tax (currently 15%) when you withdraw.

- Use it whenever on whatever.

We’ll get to each one in turn.

On January 1st, I put $5,500 in a Roth IRA account at the highest yield portfolio at Wealthfront.

Let’s break this down.

Why January 1st?

This is my highest-yield retirement investment, so I want to put the money in as early as possible each year to accumulate the greatest return.

Why $5,500?

Why a Roth IRA?

A choice between Roth IRA and a 401k mainly depends on whether you expect to pay higher marginal income tax right now or when you’re old. I expect my income tax to increase over the next decades for personal reasons (I expect my income to grow) and for Wagner’s Law reasons: taxes seem to grow inexorably in every advanced economy. All the macroeconomic trends I see (aging population, increasing welfare, automation of jobs) point to increasing income taxes as well.

I think it’s good to have both types of accounts, so you have the flexibility of using 401k money in low-spending low-tax years and Roth IRA money when you finally buy the ticket to Mars.

You can also roll-over a 401k into a Roth IRA, paying income tax on the amount. If you expect to have a year with very little income, such as taking a break for travel or child rearing, you should invest more in a 401k ahead of that and then roll over in the low-income year.

Why high-yield?

I don’t plan on using this money for the next 30 years, so I hold it in the highest-yield / highest-risk portfolio available to me: 90% stocks, a third of which are in emerging markets which are riskier and more lucrative. The longtime horizon lets the high yields compound, while the high risks smooth out over time in accordance with the law of large numbers.

Why Wealthfront?

Schwab holds a high percentage of cash, which can be overcome just by investing a bit more and keeping less in your checking account. But since the Roth IRA has a hard contribution limit, that’s not an option. Since the IRA is high-yield, Every dollar of cash in your IRA costs you a lot in forgone returns.

I put almost my entire bonus in my employer’s 401k, and little else otherwise.

Our 401k is with a mutual fund that charges an average of 1.6% fees, and we have no choice about it. I swallow the fees because the spreadsheet tells me that the $5,500 in the IRA are nowhere near enough for a happy retirement. Of course, if your employer matches 401k contributions you should max those out – that’s free money.

I draw the 401k from my bonus for tax reasons. I pay income tax every two weeks based on that period’s prorated income. On the salary period when my bonus arrives my income tax hits the highest bracket – around 20% more than my average income tax. It takes more than a year to get that tax refunded, so if I paid the tax I would be lending 20% of my money to Donald Trump at no interest, instead of making 7% return on it myself.

Keeping my hard earned cash away from the clutches of Donaeld the Unready is both a duty and a privilege.

Once a month after I pay my credit card bills I invest the extra remaining cash in personal accounts.

I have personal accounts at both Schwab and Wealthfront. The former is lower yield (only 60% in stocks, mostly large cap) and holds 9% in cash, so it’s the first one I would draw on for near-term expenses. The Wealthfront account is riskier since it’s for the medium term (~10 years) but a little more conservative than the Roth IRA.

The riskiness of the personal accounts should depend on your overall financial situation. I’m in good health, have no kids and a stable job. Whenever one of those things changes, I will switch the portfolio to a lower risk allocation like 30% stocks – 70% bonds.

So there you have it. Some are people are unsatisfied with the average, and in seeking to outsmart the average end up doing much worse. Others feel rich and happy with their lot, and they let time and compound interest make them even richer. And while you ponder the philosophical implications of that, there’s still time to book your Wealthfront Roth IRA investment for the 2016 tax year and keep your 2017 allowance.

Getting rich slowly takes time, best get started now.

This might be the most practically useful post ever. Thank you, I’m poor currently but I’ll definitely heed your advice once I become non-poor.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Would love a 3 year update – did you become not poor?

LikeLike

Shameless plug: I made a long term personal finance planning simulation app that is basically like your spreadsheet but with a nicer interface.

http://thume.ca/stashline

LikeLike

Just a quick piece of nuance to add: the growth in popularity of index funds will at some point lead to a giant bubble in companies which are found in the major indices. All these S&P 500 index investors are just pumping up the value of the stocks in the index (with a higher weighting on the companies with large market cap, e.g. Exxon-Mobil, Walmart, Alphabet, etc.) regardless of the actual value of their assets, revenue, or growth potential. In the hypothetical scenario where 100% of investors are passive, then these companies could theoretically make no money at all, and the demand for their stock would keep going up via new investments until the whole pyramid collapses. So there is probably an equilibrium point where index investors and active investors make about the same amount, but I have no idea where that might be.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s a good point, but I guess it’s not something that people like me and my readers should worry about. The few really smart hedge funds probably do make some of their money from exploiting the predictability of index funds, but for people with less than eight figures to invest index funds are still far and away the best option. Yes, of everyone only bought indices it would be bad, but everyone doesn’t so you still should.

On a more specific point, the S&P 500 is really underdiversified in my opinion and American large-cap stocks can’t be the extent of one’s investments. Global indices like the FTSE All World cover more than 7,400 companies in 47 countries, and within the US itself there are indices that track thousands of smaller companies and can help you diversify.

LikeLike

Are there commentators from Europe (germany), who know about the details here? Especially where to invest and how this interacts with the state pension scheme.

LikeLike

Does contributing when you get your bonus to avoid taxes also work with charitable donations?

Also, if your company gives you stock options, is it worth trading them for a more diverse investment, or are there a bunch of fees/taxes on that that make it a bad idea?

LikeLike

I think both questions depend on the specifics of the company you work for. With my current employer, charitable donations (unlike 401k contributions) are made from taxed income, and you get a refund a year later. Some employers also match charitable donations, so you should take advantage of that.

As for stock options, employees usually start receiving them while the company is privately owned and the options aren’t sellable. As soon as the company IPOs, you should sell all your company stock as soon as it’s legal to do so because investing in the company that pays your salary is multiplying your risk.

LikeLike

All in all a good guide.

You should probably put more emphasis on the fact that you only put so much in high-yield because of your long time horizon, lest anyone with a shorter time horizon get the wrong idea. A rule of thumb with equities is that half the value could be gone tomorrow.

Worth noting that buying low-cost indices yourself is really only marginally harder than using a robo-advisor, and can actually have lower fees* (making your chart a bit misleading). Vanguard and Fidelity are both good options for this, though there may be others.

Not sure if you’re familiar with Bogleheads.org, but it’s a good place to check out for anyone who was interested enough to read the whole thing, and a good place to start for readers who the advice isn’t a perfect fit for.

Muni bonds in a Roth IRA are an unforgivable crime against investing as an art, if you see it as one, but not a huge deal otherwise.

*Robo-advisors can do fancy tax optimizations, which are a bit more annoying to do yourself, and which probably more than make up for their fees if the alternative is not doing them–but this concern doesn’t apply to the Roth IRA, which is untaxed anyway.

LikeLike

Thanks for the comment, a lot of good stuff here.

I mentioned that my highest yield (and highest risk) portfolios are for retirement, and the shorter term ones the % of stocks is lower.

Wealthfront holds no muni bonds in a max-risk Roth IRA, and only 0.6% cash. The main point of muni bonds is the tax break, so if you hold those in an untaxed retirement account it’s a crime against math, and not just art :)

Finally, I don’t think that the tax loss harvesting is that useful. All it really does is push your taxes to future years. If you anticipate your tax rates to rise (i.e. you earn more in the future) it just loses you money. I guess tax loss harvesting may be worth it if Trump announces changes to the income tax that would go into effect into 2018, but I wouldn’t hold my breath on that one.

LikeLike

I’m probably being overly cautious about the high-risk stuff–my gut reaction was that there should be literal red bolded warnings somewhere, but on a reread it’s pretty clear.

I read that Wealthfront holds >10% munis and thought that meant all Wealthfront. That makes more sense.

I do think you’re underestimating tax loss harvesting, though. For one thing, the long-term capital gains tax rate is flat from about 40k to 400k annual income, so many people don’t need to worry about going up a bracket any time soon. The tax deferral can be like an interest-free loan, and if you donate you can manipulate which lots you donate to further optimize.

But even I don’t really worry about all that stuff in practice. The real power is the $3,000 a year of income you’re allowed to offset with capital losses. If you make $40k a year, your income tax rate is not just higher than your capital gains rate, it’s higher than the highest capital gains rate. So trading income tax today for capital gains tomorrow is a big win.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This mostly applies if your harvestable losses are around $3,000 a year on average. At my modest wealth I’m far from that. This means that by harvesting losses I’m only trading income tax today for income tax next year and my potential gain is only the yearly return and not the gap between cap gains tax and income tax.

With that said, Wealthfront does daily tax-loss harvesting for free. I read your comment, read the Wealthfront FAQ and signed up. Thanks!

LikeLike

“This means that by harvesting losses I’m only trading income tax today for income tax next and my potential gain is only the yearly return and not the gap between cap gains tax and income tax.”

At least one of us is confused about something. Why exactly does it mean that?

LikeLike

I had a word missing: next year.

Anyway, what I mean is that if I don’t sell a stock at a $100 loss to offset $100 in income tax this year, I can (on average) sell it next year for the same effect. All I lose is the opportunity to earn interest on the $30 of taxes I would have paid on the $100 of income. Only if you expect to have more than $3,000 offsettable losses next year do you need to rush and grab the losses this year.

I may be still confused about something, but at least now I hope that you aren’t :)

LikeLike

I think I do see now.

I believe your “on average” is misleading, because harvesting in a given year has potential upside but not downside. That is, if you harvest now and the asset’s value goes back up, you’ve locked in a loss you might never see again; whereas if you harvest now and it goes further down, you can just harvest the remaining difference.

For some wholly unnecessary illustration, I tried simulating loss harvesting on a normal random walk. I’m assuming there’s one asset whose price changes once per year, with the changes generated by a normal distribution. If we harvest as much as possible, we’ll get losses equal to the minimum net change, whereas if we don’t we’ll get losses equal to the final net change (if it’s negative).

Findings are that if the normal distribution’s mean is zero, then after two years, eager harvesting will capture about 20% more losses; after five years, that’s up to about a 33% advantage.

But the mean change we expect on our assets is not zero. I tried with mean .1, stddev .18, according to some cursory googling for the values of the S&P 500. The positive average change makes it extra important to lock in any losses that do occur; and I find that after five simulated years of holding S&P, the eager harvesting strategy harvests over three times as many losses.

Python code below:

def walk(n, mu, sigma):

minimum = 0

value = 0

for i in range(n):

change = random.normalvariate(mu, sigma)

value += change

minimum = min(minimum, value)

return minimum, value

def avg_outcome(walk_fn, n):

using_min = 0

using_end = 0

using_end = 0

for i in range(n):

(minimum, end) = walk_fn()

using_min += minimum

if end < 0:

using_end += end

return (using_min, using_end, using_min – using_end)

randwalk2 = lambda: walk(2, 0, 1)

avg_outcome(randwalk2, 100000)

-> (-68324.78109756722, -56635.67402680817, -11689.107070759048)

randwalk5 = lambda: walk(5, 0, 1)

avg_outcome(randwalk5, 100000)

-> (-128613.03804740353, -89133.50302418224, -39479.535023221295)

spwalk = lambda: walk(5, .1, .18)

avg_outcome(spwalk, 100000)

-> (-6818.068936028902, -2073.347403395457, -4744.721532633444)

LikeLiked by 1 person

I wonder why Wealthfront couldn’t explain it as clearly, and I’m a bit embarrassed I didn’t take the time to think about seriously this myself.

Thank you for making the effort, I have now switched on tax loss harvesting on all my accounts and endorse everyone doing the same.

LikeLike

TIL: You can treat $3000 of investment losses (subject to low tax) like $3000 of lost earnings (subject to high tax)!

Now, I’m trying to figure out if IVV and VOO count as

“substantially identical”. (Investopedia and supposedly robo-advisor think they don’t which is weird, because “equal” should imply “substantially identical”. But people are apparently afraid that the IRS will turn around and execute them. OTOH, this gives Vanguard and iShares reason to both exist.)

LikeLike

Second order answer: Yes you can, but you blast open the distribution of your potential outcomes, including introducing a massive amount of idiosyncratic risk. If you already have a robust saving plan in place, and wish to take extra money you can afford to lose that you would have otherwise spent on consumption goods, and invest it in companies you have a long-term belief in, this is an OKAY thing to do. But it is not trivial, and if you learned anything from what our author just wrote, or what I just wrote, you’re probably not smart enough to do it :)

LikeLike

Thanks for the article. Are there any updates you’d add to this (for example saw that you’d do automated tax harvesting in the comments).

Any books you’d recommend on these topics?

LikeLike

Has anyone here worked for themselves? What’s the next-best option for a 401k when your employer is you? Is this something I can easily set up for myself at an LLC?

LikeLike

I just want to copy some stuff from my other comment here:

https://putanumonit.com/2019/06/03/get-rich-real-slowly/comment-page-1/#comment-56416

which I made while thinking I was on this post, but I think is relevant in all places Wealthfront is mentioned here:

I actually signed up for Wealthfront from this post… kind of. I noticed an arbitration opt-out clause in their TOC, which I read all like 200 pages of, and emailed them to initiate it. They told me they were not offering “custom contracts” at this time and that the arbitration opt-out would not be honored. When I replied that the contract said that communications by email or other channels would not be deemed valid, they said that I could either close my account or they would forcibly.

I really wanted to use their service, since it seemed like something interesting that was a good idea and would be beneficial. I guess I am looking at other options though, because I will not store my money with a company that treats their own contract like a cage for me but a weapon for them.

If anyone has further information on this, I turned on replies for comments.

LikeLike

I just came across this guide and it seems very sensible. I thought I’d just say, though, that your retirement portfolio calculator looks overly optimistic about how much you could spend in retirement and expect to end up with a positive balance because it ignores investment volatility. This reduces the sustainable spending rate by a lot – there’s a lot of things written about “safe withdrawal rates” regarding this.

LikeLike