I try to maintain equanimity regarding most bitter conflicts raging in the world, but I do get quite worked up regarding proper statistical methodology in psychology research. Hey, we all need our hobbies. When I wrote a post about it, I tried to focus on constructive advice on how to do science better (calculation of experimental power), but I couldn’t resist taking some shots at scientists who neglected to do that.

In particular, I criticized Dana Carney, Amy Cuddy and Andy Yap for publishing the infamous power pose paper, a useless experiment that had 13% statistical power.That is, the experiment had a 13% chance to detect the effect had one existed. If it turns out that the effect doesn’t exist, the experiment was 100% worthless.

The paper is called “Power posing: brief nonverbal displays affect neuroendocrine levels and risk tolerance” so it actually looked at three effects: two neuroendocrinal (cortisol and testosterone) and a behavioral risk tolerance effect. Even a blind person may hit an occasional bird when shooting three arrows, but CC&Y were not in luck: none of three effects turned out to exist. That wasn’t unexpected: holding a strange pose for a minute will not affect most things in your life.

Last month, it seemed that this silly controversy has been decisively resolved in favor of truth and reason when lead author Dana Carney posted this on her academic website: (emphasis in original)

Since early 2015 the evidence has been mounting suggesting there is unlikely any embodied effect of nonverbal expansiveness (vs. contractiveness)—i.e.., “power poses” – – on internal or psychological outcomes.

As evidence has come in over these past 2+ years, my views have updated to reflect the evidence. As such, I do not believe that “power pose” effects are real.

Any work done in my lab on the embodied effects of power poses was conducted long ago (while still at Columbia University from 2008-2011) – well before my views updated. And so while it may seem I continue to study the phenomenon, those papers (emerging in 2014 and 2015) were already published or were on the cusp of publication as the evidence against power poses began to convince me that power poses weren’t real. My lab is conducting no research on the embodied effects of power poses.

To drive the point home, Carney lists 10 methodological errors and 3 confounders of the original study, declares that power study is a dead-end for research, and moves on.

The third author, Andy Yap, switched academic fields and continents to study organizational behavior at an elite French business school. He probably tells people that the power posing thing was this other Andy Yap in psychology. Or the other other Andy Yap, the one showing off his killer pecs on Instagram.

Science advances one funeral at a time. – Max Planck

more funerals => science advances => better weapons => more funerals – Steven Kaas

@stevenkaas Popular science advances one mass funeral at a time. – Me

In between funerals, science advances when scientists say “oops” and stalls when they don’t.

Arguing in favor of Cuddy saying “oops” are: the invalid design of the original experiment, 6 years of contradicting data, the acknowledgment of both by the study’s lead author.

Arguing against Cuddy saying “oops”: her book ($28 on Amazon), and her speaking fees (a lot more than $28).

Which side are you betting on?

I was surprised by a recent statement that the power pose effect is “not real” and I want to set the record straight on where the science stands.

That’s exactly where the science stands: the power pose effect is not real. Not “not real”, just not real.

There are scores of studies examining feedback effects of adopting expansive posture (colloquially known as “power posing”) on various outcomes.

“Various outcomes” sounds like a lot of other people are shooting arrows in the air. Who knows, maybe some will hit. If I was a researcher, the first thing I would test is the effect of prolonged power posing on back pain.

The key finding, the one that I would call “the power posing effect,” is simple: adopting expansive postures causes people to feel more powerful. The other outcomes (behavior, physiology, etc.) are secondary to the key effect.

Bullshit. That’s a lie of Trump-level brazenness, it’s contradicted by the very title of the paper Cuddy talks about, the one with the “neuroendocrinal” and the “risk taking”. According to Carney, the primary variable of interest was risk-taking behavior, followed by testosterone and cortisol. “Feeling powerful” is a side effect, listed at the end, with no accompanying chart, almost as an afterthought.

There’s a reason “feeling powerful” was an afterthought: even if it exists, it has little scientific value. It’s a self-reported measure that doesn’t necessarily manifest itself in any behavioral changes, such as actually being more powerful. If it did, we would study those behaviors directly. Being entirely subjective, “feeling powerful” is highly prone to experimenter bias. Experimenter bias is the wonderful effect that lets a scientist detect supernatural ESP, if and only if the scientist himself believed in ESP to start with. Experimenter bias is something that Carney and Cuddy themselves admitted was an issue in the original design.

However, in this case the self-reported feeling wasn’t actually the result of accidental experimenter bias. It was the result of purposeful experimenter manipulation:

The self-report DV was p-hacked in that many different power questions were asked and those chosen were the ones that “worked.”

Carney should be commended for being so forthright, it takes courage to admit such a thing with no sugar-coating about your own work. She must have stood in one hell of a power pose before writing this.

Back to Cuddy:

I also cannot contest the first author’s recollections of how the data were collected and analyzed, as she led both.

Sniping at Carney doesn’t make Cuddy right, it just shows the contrast between a scientist and a charlatan.

By today’s improved methodological standards, the studies in that paper — which was peer-reviewed — were “underpowered,” meaning that they should have included more participants.

That’s not what “underpowered” means. In the power posing case, it means “useless”. It’s not that the original experiment discovered some truth and better methodology would discover more. The original experiment abused pure random noise until it got a (miscalculated) p-value of 5%, and that was enough for the “peer reviewers”. Some of these same peer reviewers and psychology journal editors are calling people who insist on using correct statistical analysis “methodological terrorists” and sabotaging their academic careers.

Open science must be inclusive.

In one word: no. In two: fuck no. Science doesn’t need to be inclusive, or egalitarian, or warm and fuzzy. It needs to be correct. And in order to be correct, science must reject theories that have proven to be bullshit, like phlogiston and elan vital and power posing.

Finally, I am concerned that the tenor of discussions like the one that has been unfolding on power posing, and the tendency to discount an entire area of research on the basis of necessary corrections or differences between scientists’ assessments, may have a chilling effect on science.

The reason people discount power posing research is that the first 50 Google hits on “power posing” are about Amy Cuddy’s article. If she shut up about that one pathetic experiment and let the “scores of scientists” she mentions do their work, we might actually discover some truth about embodied cognition. Perhaps all the research in this area is underpowered given how much noise there is and how weak the effects are. Perhaps the only way to study the field may be to run experiments with 40 coauthors and 4,000 subjects, like we do in medicine. Before we learn anything new about the field, we should discard the things we know are wrong.

“Power Posing: Brief Nonverbal Displays Affect Neuroendocrine Levels and Risk Tolerance” is the worst thing that could have happened to embodied cognition research. It contributed negative knowledge to the field. Cuddy’s refusal to let go of it for selfish reasons makes life so much harder for the psychologists trying to move the science forward.

Great post. I agree with a previous commenter that these first-year reviews are superb.

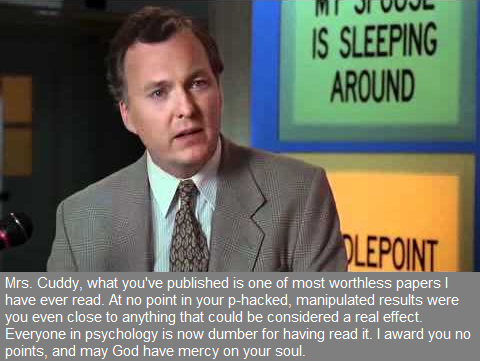

The image at the bottom was hilarious, but I read it on my phone and, before I read the caption, the image looked like an ad. I almost skipped it altogether until I rembered your policy of no ads. I’m glad I remembered. O’Doyle rules!

LikeLike